This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

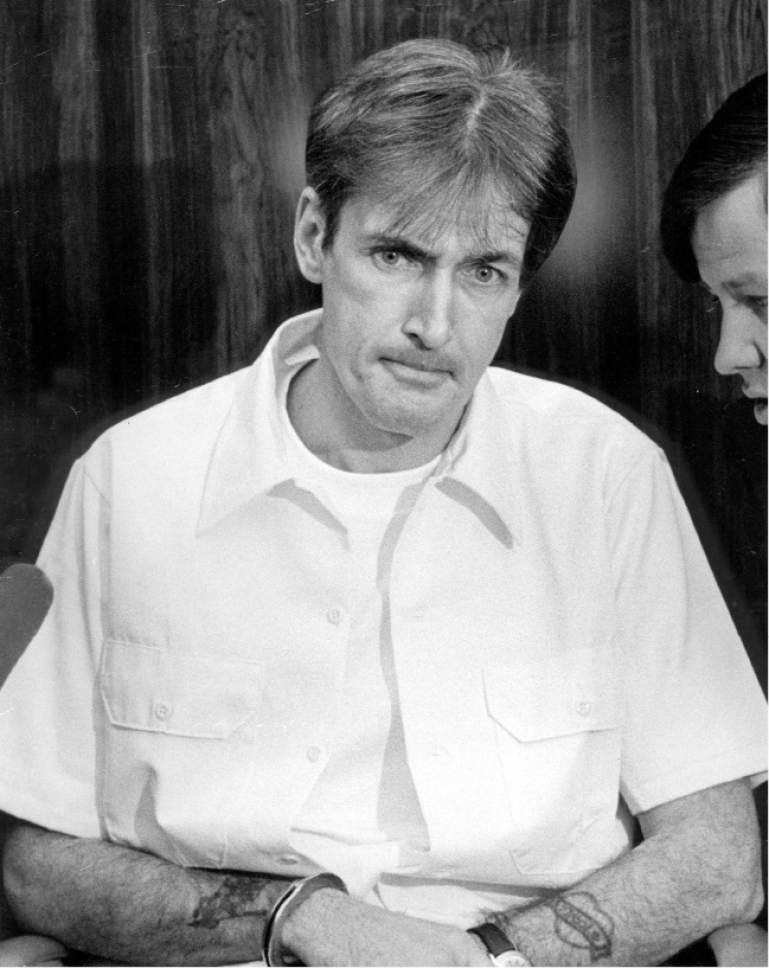

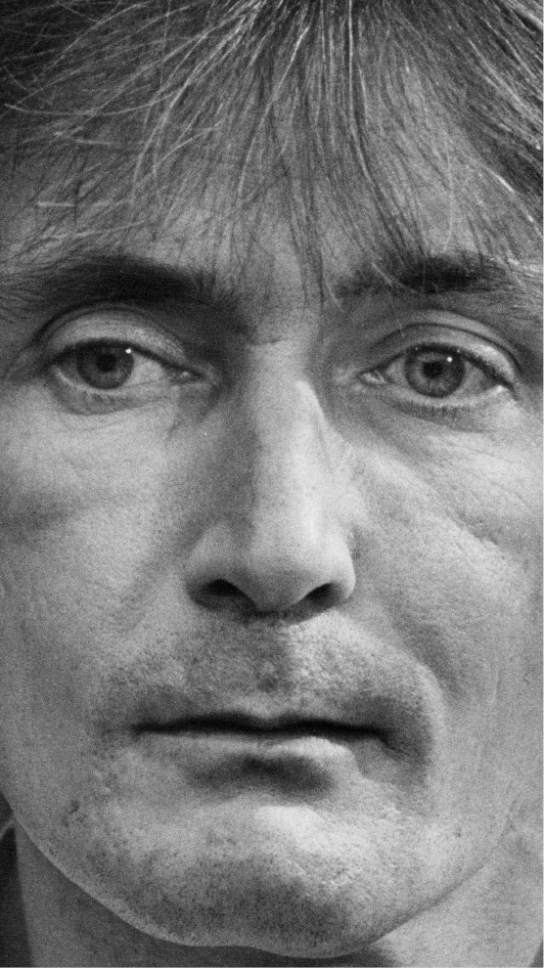

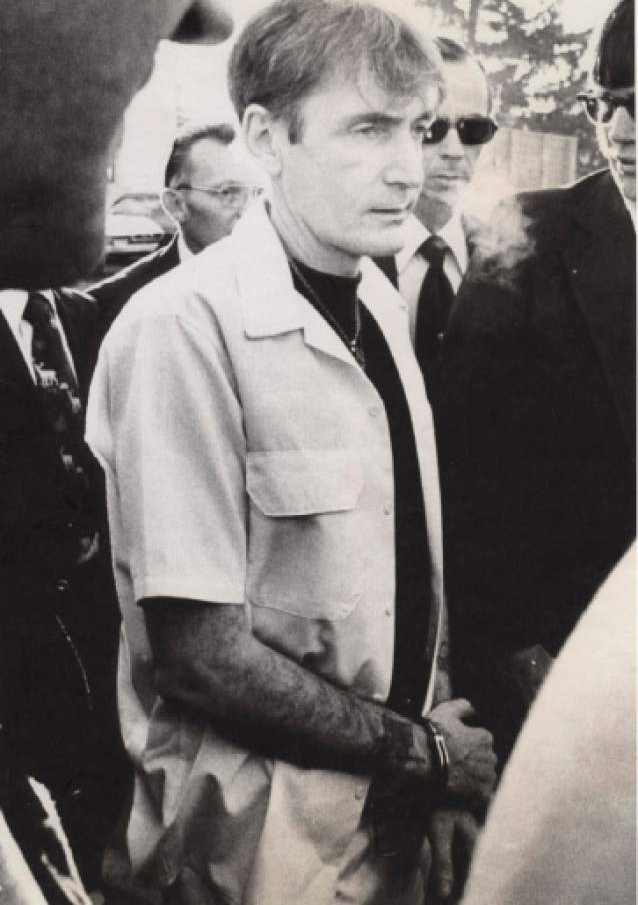

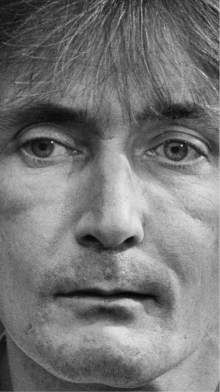

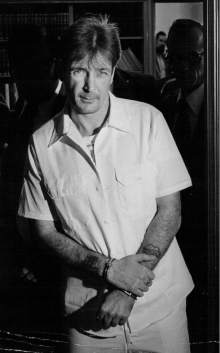

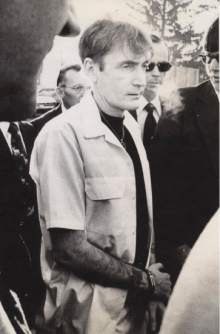

Gary Gilmore was 36 years old when he welcomed the bullets from a five-member firing squad at the Utah State Prison, becoming the first inmate killed following a 10-year national moratorium on capital punishment.

His death on Jan. 17, 1977, which reopened the gates to the death penalty, has been memorialized in American culture through widespread news coverage at the time, followed by books, a movie and even a new documentary that will air two days before the 40th anniversary of Gilmore's execution.

The documentary, "Dead Man Talking: The Execution of Gary Gilmore," airs in Utah on REELZ at 7 and 9 p.m. on Sunday, two days before the 40th anniversary of his execution.

Raised by an abusive, alcoholic father outside Portland, Ore., before spending much of his life in state custody and eventually coming to Utah and killing two people, Gilmore was a man the state deemed fit to kill. He agreed.

"The way he got to the front of the line — there were obviously many more people who committed murders in states that had state-of-the-art death penalty statutes," said Paul G. Cassell, a law professor at the University of Utah, who was interviewed for the documentary. "He was a volunteer, which meant they didn't have the full appellate delays."

Gilmore became a household name after he used a stolen Browning .22-caliber automatic pistol to kill 25-year-old Bennie Bushnell, the manager of Provo's City Center Inn, and 24-year-old law student Max Jensen.

Cassell says Gilmore's case has persisted, in part, because he was the first person executed after the U.S. Supreme Court ended its own ban on executions in 1976.

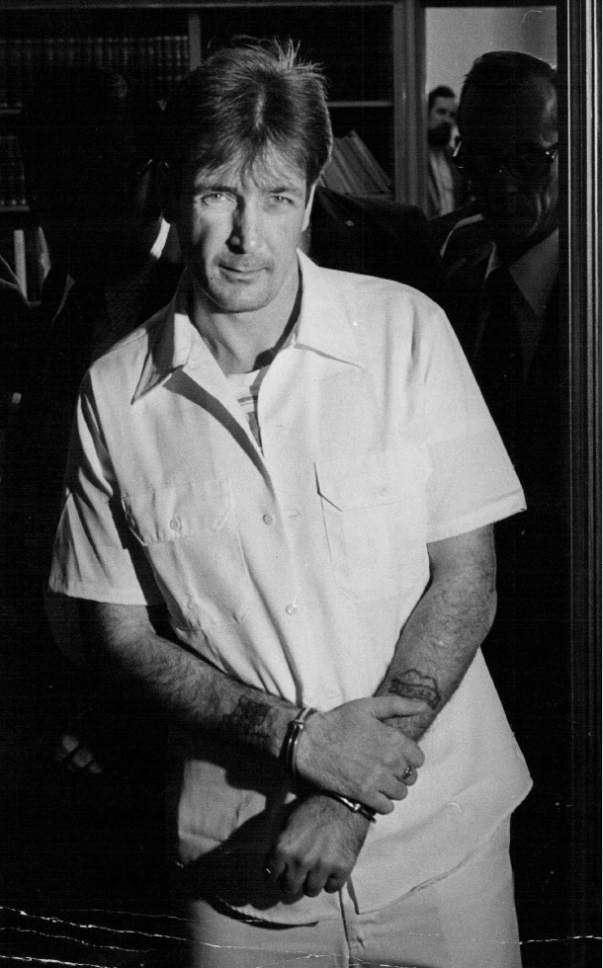

Gilmore decried attempts to prolong his life through appeals to state and federal court. When the process wasn't quick enough for Gilmore, he tried to kill himself.

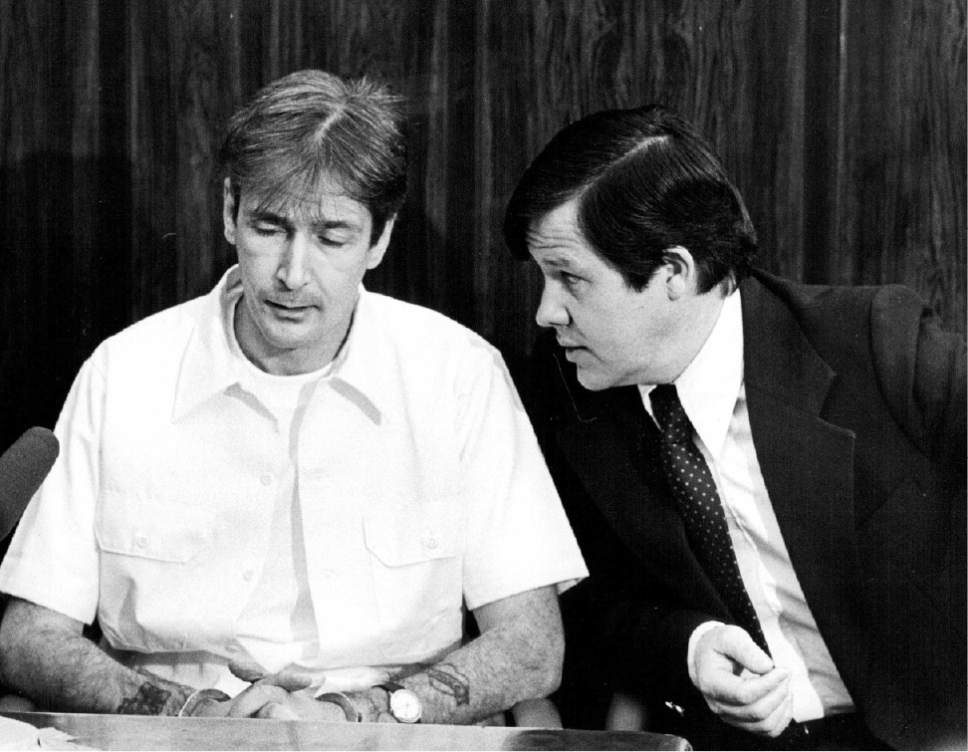

Trying to persuade federal courts to prevent Utah from killing Gilmore was the hardest case former trial attorney Virginius "Jinks" Dabney was ever involved in. And it's a case that made him change his opinion of the death penalty.

When the Utah chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union approached Dabney in 1976, he remembers them asking him to monitor the Gilmore case for a week or two while another attorney on the case was out of town.

"I said, 'Well, I'm kind of in favor of the death penalty,' " the 73-year-old Dabney, of St. George, said Thursday.

Still, the ACLU needed help and Dabney was known in legal circles for having recently won a criminal trial in Salt Lake City. So he accepted the assignment, he said, not knowing the impact that trying to save the life of a man who wanted to die would have on him.

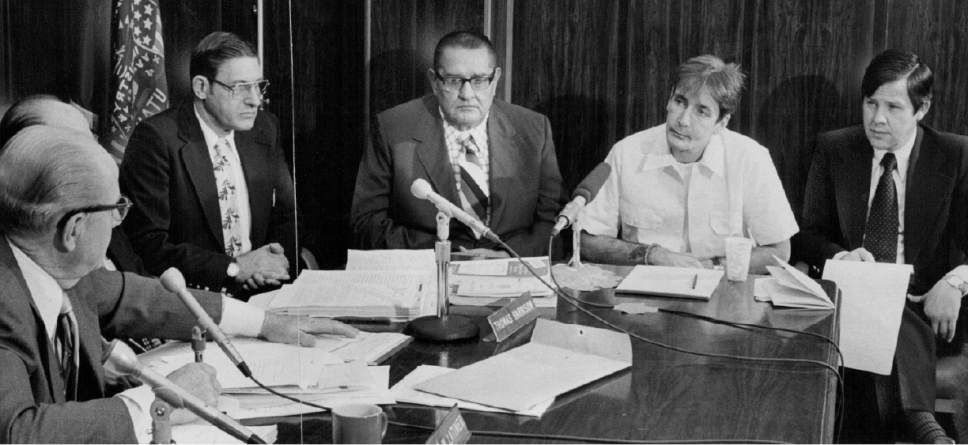

Dabney, who was also interviewed for the documentary, believes courts waived rules and deadlines for hearings, which sped up the process that led to Gilmore's execution. He also believes state officials and Robert B. Hansen, Utah's attorney general at the time, wanted the Beehive State to be the first in a decade to execute a prisoner.

In the hours before Gilmore's impending death, Dabney asked the U.S. District Court in Utah to grant a motion that would halt the execution.

"What case would be more stressful than this? Knowing I could say one thing wrong, get a motion denied and a man could die because of it," said Dabney, who argued the state was misspending tax dollars by unconstitutionally killing a prisoner.

While Gilmore was pleading with anyone who would listen that he wanted to die, the court agreed with Dabney and ruled hours before the scheduled execution to temporarily halt Gilmore's death.

The win was short-lived, however, as state prosecutors quickly flew to Denver to ask the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals to overturn the order. The state's motion was approved. Utah could kill Gilmore, who welcomed the news.

"Let's do it," Gilmore famously said moments before he was executed.

His death preceded hundreds of other prisoner executions.

"Death penalty foes were correct in that once Gilmore was executed, a 'barrier' both political and psychological was broken and those states that wanted to actually [use] the death penalty had a path towards using it," Joshua Marquis, a district attorney in Oregon who, like Cassell, is a proponent of the death penalty, said in an email.

While Gilmore's case may have forged the path back to capital punishment, Ralph Dellapiana, a defense attorney who is director of Utahns for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, says the number of prisoners killed in recent decades has declined.

But Dellapiana said that as long as the death penalty remains an option, there is a possibility that an innocent prisoner is executed.

"Some people point to these types of cases as ones where [they say] 'See, that's why we have to have the death penalty,' " Dellapiana said. "But the problem is that it's not just those few cases where the death penalty is applied."

Having entered the case as a proponent of capital punishment, Dabney says he now opposes it, saying if prosecutors and judges didn't slow down the death of one man on death row, there are likely others — potentially innocent — who face the same fate.

"Even if some guy says, 'I don't want an attorney,' to go through that many courts, somebody should have said, 'Look, we need to slow this down,' " Dabney said. "It was a very dark day for the Utah legal system. It was just a sad day."

Twitter: @TaylorWAnderson