This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

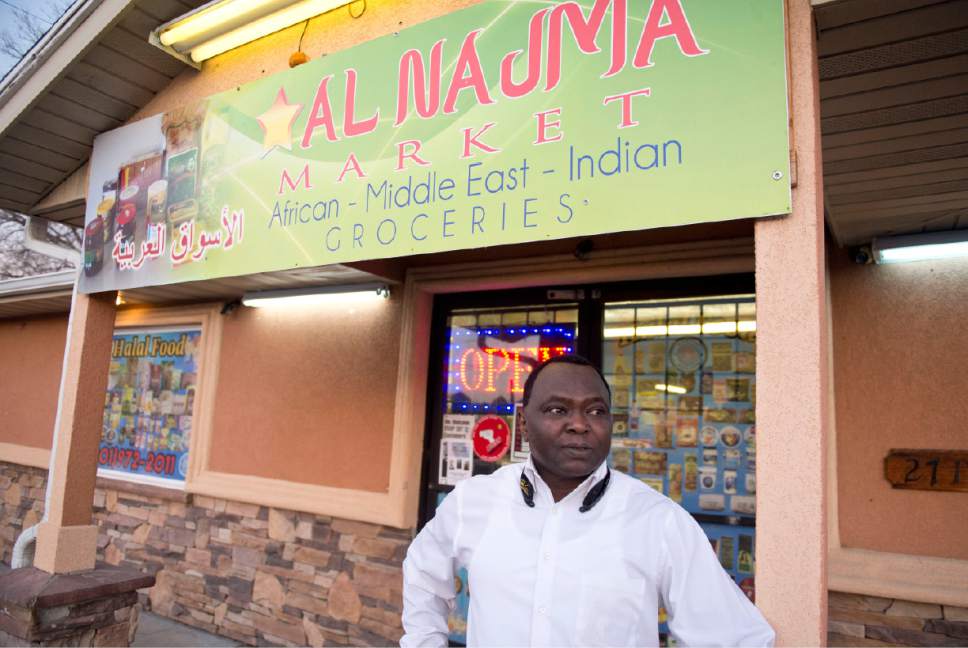

It's been a year and three months since Ibrahim Abdalla has seen his wife, and after an executive order Friday, he's not sure when they'll meet again.

Abdalla, 54, of West Valley City, fled from his genocide-plagued homeland of Sudan in 1998, and after living for years in a Jordanian refugee camp, he was admitted to the United States in 2004. He worked to become a U.S. citizen and establish a life here, opening an ethnic grocery store in Salt Lake City with his cousin. In October 2015, he took a trip overseas to get married.

After returning to America, he's spent time working to bring his wife here and start their new life together.

Then, on Friday, President Donald Trump signed the order suspending refugee admissions for 120 days, placing an indefinite ban on immigrants from Syria and a 90-day ban on people from Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen.

"This is hard for me, [not knowing] how she will come," Abdalla said Saturday. "I'm wondering how can we get my wife. ... I don't see how she can come."

Things had seemed to be moving along for Abdalla's wife, he said. She had her interview at the U.S. Embassy and submitted her passport to U.S. officials in November — generally the last step in the process before a visa is granted.

For three months, she's waited to get her passport back and heard nothing, Abdalla said.

Even if she is granted a visa, he said, the executive order could stand in the way of her journey.

Abdalla has a meeting this week with attorney Brian Tanner, who says he has several clients in a similar situation.

One woman from Somalia — now a U.S. citizen — has been separated from her son for 12 years, after he was mistakenly listed as a nephew or stepson instead of a biological son on papers and denied admittance to the U.S., Tanner said.

The son was born after his mother fled Somalia, Tanner said, but because of the lack of birthright citizenship in East African countries, he's a citizen of a Somalia — a country in which he's never stepped foot.

Tanner submitted papers last week for the son to come to the United States, he said, but under Trump's executive order, the son's citizenship disqualifies him from joining his mother, forcing him to continue living in and out of refugee camps — as he has for the past decade.

"We're really worried that they won't be able to see each other again," Tanner said.

Aden Batar, the refugee-resettlement and immigration director for Catholic Community Services of Utah, feels disheartened as he watches the United States close its doors on refugees.

Batar came to the U.S. from Somalia 23 years ago.

"Refugees from those countries, they cannot go back," he said. "I'm originally from Somalia, [but] Utah is my home because I still can't go back."

The refugee-resettlement program "saves lives," he added, and it doesn't put national security at risk. Asha Parekh, director for Utah Refugee Services in the Department of Workforce Services, said the office has already heard "increased concerns" from refugees over what might happen as a result of the executive order.

"We cannot turn our backs on those refugees who are already here," Parekh said. "Part of our state's heritage is to accept people who have been persecuted and driven out of their home. That is Utah."

There's a sense of uneasiness among refugees, Parekh said, as reports of bullying and persecution have grown over the last year.

Refugees have been arriving in Utah every week, Batar said, but the ban will change that. While immigrants were detained at airports elsewhere in the country, there was no indication that had occurred in Salt Lake City. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security, which was fielding calls from reporters, did not answer several phone calls Saturday from The Salt Lake Tribune.

Since resettlement programs began in the 1970s, Utah has accepted 60,000 refugees from 50 countries, Batar said. The new executive order is "devastating" for them.

The Trump administration should look at the situation in a "humane way," Batar said, adding that Congress has a responsibility to fulfill past commitments to accept refugees.

"Our president needs to get the right information," he said. "He needs to go visit the refugee camps and see how they live."

Refugees have been victims themselves, he said, experiencing torture, bombings and loss of loved ones firsthand. Refugees are already carefully vetted, he said, and become contributing members of U.S. society.

"Different consular officers and the refugee-resettlement people do the best job possibly can to verify that people are truly fearing for their lives," Tanner said.

Refugee visas aren't easy to come by, he added, and if people truly were intent on causing problems for the United States, they could find an easier way to do it.

"The idea of going and trying to sneak into a refugee camp and essentially languishing there under really terrible conditions for months and months and months, and then doing it under the pretense of 'I'm going to trick people into thinking I'm a refugee when really I'm just wanting to hurt people' — it's ludicrous," Tanner said. "People have way better things to with their time than just hang out in really substandard living conditions."

Keeping refugees out "is not American. That is not who we are," Batar said. "Refugees need our help. We're a nation of immigrants and refugees, and we can't turn our backs on them."

Coming to the United States "saved" Batar and his family, he said. "Now I'm member of community. I'm a law-abiding citizen."

He says he's also frustrated that the United States is detaining people who have worked as interpreters for the military overseas, and he's concerned how it will affect the world's view of the nation.

"If we send them back, what message would that send? Who's going to work with our forces?" Batar said. "It's not making America safe."

Utah will continue to provide support and services to refugees who are already here, Parekh said, and will try to "quell fears" by making sure they know their rights and where to report harassment.

"There is a lot still unknown about how President Trump's executive order is going to affect refugees in the long term," she said. "We want to get all of the details and information before we act."

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on Saturday issued a statement expressing "special concern for those who are fleeing physical violence, war and religious persecution."

"The Church," the statement went on to say, "urges all people and governments to cooperate fully in seeking the best solutions to meet human needs and relieve suffering."

But the unknowns have refugees worried.

Abdalla spoke to his wife three days ago, but he's worried things will be different now. He tried calling today, but no one picked up.

He's "just waiting."

Twitter: @mnoblenews —

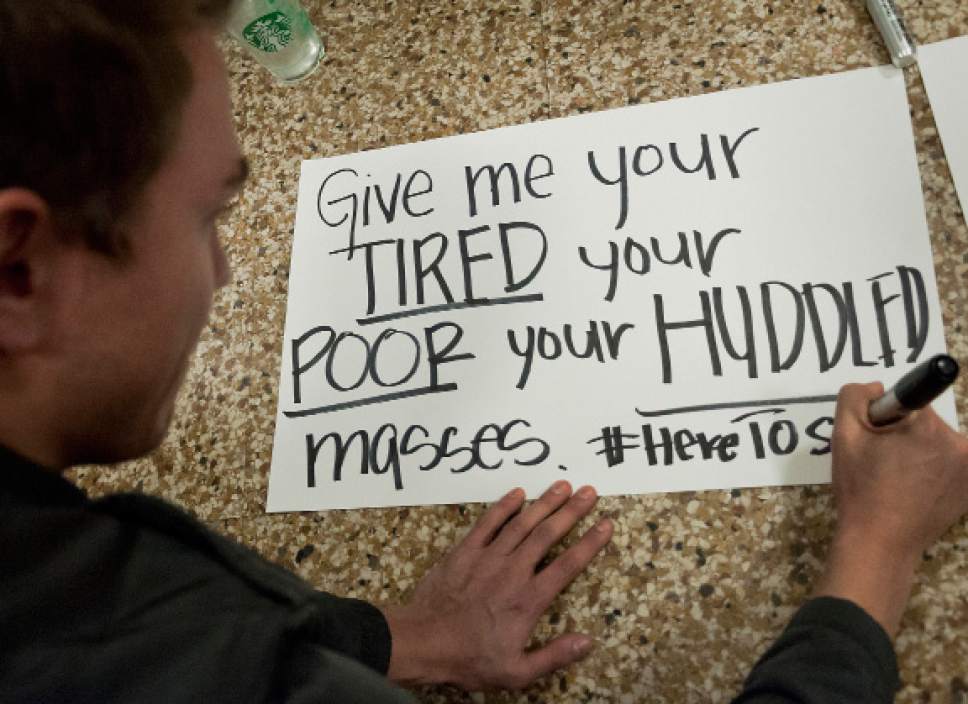

Protesters rally at SLC International Airport

Hundreds of Utahns protested President Donald Trump's executive order at Salt Lake City International Airport. There were similar protests at other airports across the country in response to how some immigrants entering the country were detained at airports hours after Trump signed the order.

While there were no reports of detentions in Salt Lake City before the order was temporarily halted, several in the crowd said they came to show their opposition to the executive order.

"We go to war to defend the freedom of all people," said Bart Tippetts, 71, who fought in Vietnam in 1966 and 1967.

Ella Mendoza, an undocumented immigrant from Peru, said she walked through the same airport halls when she came to Utah 14 years ago. "My message is here," Mendoza said. "No wall. No ban."

The youngest in a stream of people to tell stories through a megaphone at the center of a circle of supporters was Millie Kraatz, 8, of Salt Lake City, who told the crowd she was scared. "I don't think it's fair to not let them in just because they're different," Kraatz said while standing next to her 10-year-old sister.

Taylor Anderson