This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In Utah's fight to rescind Bears Ears National Monument, Republican politicians have refocused a long-standing campaign against another big monument two decades after President Bill Clinton appeared on the rim of Arizona's Grand Canyon to set aside Utah's Grand Staircase, Escalante canyons and the coal-rich Kaiparowits Plateau.

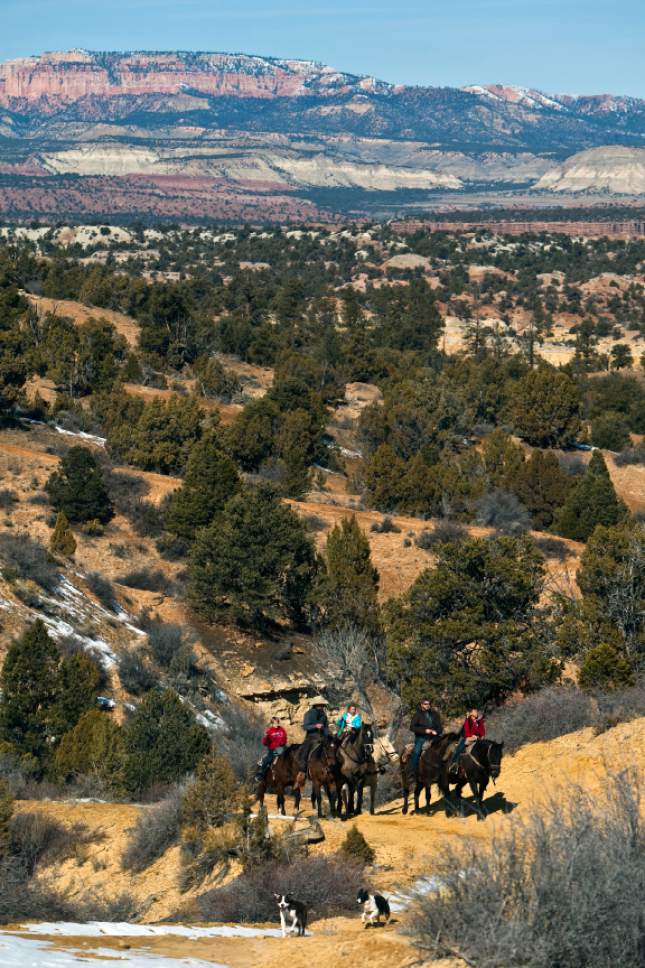

Many acknowledge the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument is driving a burgeoning tourist economy in Garfield and Kane counties, where new hotels and restaurants are opening to serve an influx of visitors to the monument and surrounding redrock desert. But the designation has come at a price to local culture and tradition by displacing cattle ranchers, closing roads and thwarting coal mining and other commercial activities, according to backers of a resolution aimed at shrinking the 1.9 million-acre monument.

On Monday, the Kane County Commission passed a similar resolution, calling on Congress to "reduce or modify the boundaries" of the monument to the minimum area needed to protect antiquities mentioned in Clinton's proclamation.

About 125 people attended the special meeting, according to Kanab resident Noel Poe, who is also president of Grand Staircase Escalante Partners. "The majority opposed the resolution," said Poe.

A Salt Lake Tribune-Hinckley Institute poll last fall found Utah voters approve of the Grand Staircase monument 47 percent to 39 percent. The survey, conducted Sept. 12-19, found stronger support among younger voters.

But HCR12's sponsor Rep. Mike Noel. R-Kanab, told colleagues last week the monument was designated only as a gimmick to help Clinton's re-election chances, and its boundaries were enlarged to take in two proposed coal mines in the Kaiparowits' vast coal deposits.

Noel said the monument has damaged the availability of well-paying employment and residents are leaving the county. Meanwhile, he said, "There are jobs to make beds and to clean toilets and to do the tourism business."

Critics believe Noel and his supporters are distorting the facts in an effort to assert greater local control over scenic landscapes owned and valued by all Americans.

They note that permitted grazing allotments have barely changed in the 20 years since the monument's creation. Hundreds of miles of roads remain open to the general public, ATV riders and permitted users. And commercial recreation abounds on the monument, supporting dozens of businesses in Escalante, Boulder, Kanab and other towns rimming the monument.

Those trends, monument supporters contend, are hard to square with HCR12's assertion that the monument "has had a negative impact on the prosperity, development, economy, custom, culture, heritage, educational opportunities, health, and well-being of local communities," and pushed Escalante High School enrollment down 44 percent.

Garfield County Commissioner Leland Pollock, who regularly testifies against the monument at the Legislature, told senators the school, which goes from seventh to 12th grade, has plunged from 140 students to 51 since 1996. The closure of a lumber mill, which pulled timber from the nearby Dixie National Forest, can account for most of the enrollment drop.

"We aren't against tourism," Pollock said, "but minimum-wage jobs don't support a family."

Citing a Utah State University study, the Legislature's Bears Ears resolution asserts that grazing on the Grand Staircase has declined by a third since the monument was created despite a presidential promise that grazing would "remain at historical levels."

The monument proclamation itself makes no such promise, instead saying that existing grazing rights and stocking levels would be governed by applicable law.

And while grazing levels have moved up and down dramatically since the monument was designated, "it is not the creation of the monument that causes those numbers to fluctuate," said monument spokesman Larry Crutchfield. "It's fluctuating as a result of available forage due to amount of precipitation."

Still, Noel contends the Bureau of Land Management went overboard with new rules that make it difficult on ranchers hoping to improve the range and access their allotments, on power companies trying to maintain and upgrade utility lines, on hunters, and on everyday folks trying to enjoy the outdoors with friends and family.

He alleges the BLM shut down 1,000 miles of roads, put an end to filmmaking and other commercial activities and limited recreational outings to "eight or nine heartbeats."

No one disputes roads were closed, but 1,000 miles remain open to general travel, including 600 miles that can be used by non-street-legal ATVs, according to the monument's own management plan. Another nearly 700 "resource roads" — short, ungated spurs leading to a rangeland improvements, such as ring tanks and corals — remain available to those who need access for livestock or other permitted uses.

Many of these routes were closed to public use at the request of ranchers who wanted to keep monument visitors away from their cattle operations, according to Crutchfield.

The monument has issued 26 film permits since 2012 and is now managing a record 115 special recreation permits. About half are for hiking and education outings. Sixteen are for hunting guides.

Outdoor recreation and geologically gorgeous landscapes are fueling a boon in Escalante, where construction permits are at an all-time high and Main Street businesses saw record traffic last year, according to letters recently sent by Escalante Chamber of Commerce to Utah House Speaker Greg Hughes, R-Draper.

"The Grand Staircase is a draw, but it's not the only thing in Garfield County," former Mayor Jerry Taylor, now a county commissioner, told lawmakers. We need to protect that but also we have to look at the rancher, the miner, the people who work in other industries. We need diversity outside tourism."

The region also needs coal, Pollock contends, asserting that the Kaiparowits holds two-thirds of Utah's remaining coal reserves. Noel argues the deposits of high-quality coal are worth $2 trillion. According to the Utah Geological Survey, however, around 9 billion tons are recoverable, an amount worth closer to $360 billion at today's depressed prices.

"We are running out of coal. We can't afford to lock it up," said Pollock, arguing the monument should be cut down to 500,000 acres to focus on the Escalante tributaries and other interesting formation sculpted in Navajo Sandstone.

But while Pollock sees the Kaiparowits as a desolate blue-clay alkali desert overrun with noxious rabbitbrush, others find the desert landscape alluring and note that it has since become world-famous for fossil excavations.

"We are rewriting dinosaur paleontology based on the science done on the Kaiparowits, that horrible gray stuff no one seems to like," Crutchfield said.

Salt Lake City resident Valerie Huitzil said she frequents the Escalante region in search of solitude and adventure. She and her friend Magdalena Jones asked lawmakers to leave the monument the way it is for future generations to enjoy.

"It's a unique and precious landscape that has shaped my life in a lot of ways," Huitzil said. "The new generation coming up is focusing on solitude and getting away from crowded national parks."

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. Brian Maffly can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713.

Twitter: @brianmaffly