This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

John Swallow's defense team tore into a star prosecution witness Thursday, shifting the focus from the former Utah attorney general's free stays at a California beach resort to an alleged $35 million fraud involving a Draper train station.

Attorney Scott C. Williams pressed businessman Marc Sessions Jenson about his assertions that Utah Transit Authority officials, developers and other high-powered politicians had gathered at Pelican Hill as part of the alleged station scheme.

Williams may have been setting the stage for defense witnesses who would rebut that testimony, casting doubt on accusations aimed at his client.

At a hearing two weeks ago, Jenson dropped a bombshell, naming influential officials who he said were at the June 2009 meeting, including then-U.S. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev.; Utah House Speaker Greg Hughes, R-Draper, who was a member of the Utah Transit Authority board at the time; developer Mark Robbins; and Bruce Jones, the now-former UTA attorney.

Also present, according to Jenson, were then-Utah Attorney General Mark Shurtleff and Swallow, then a lawyer in private practice and a chief fundraiser for Shurtleff. In addition, Jenson testified that UTA board members received payments as part of the station scheme.

Hughes has adamantly denied he was present and that board members received any money. Shurtleff has labeled Jenson a liar, and he and Hughes may be called as defense witnesses.

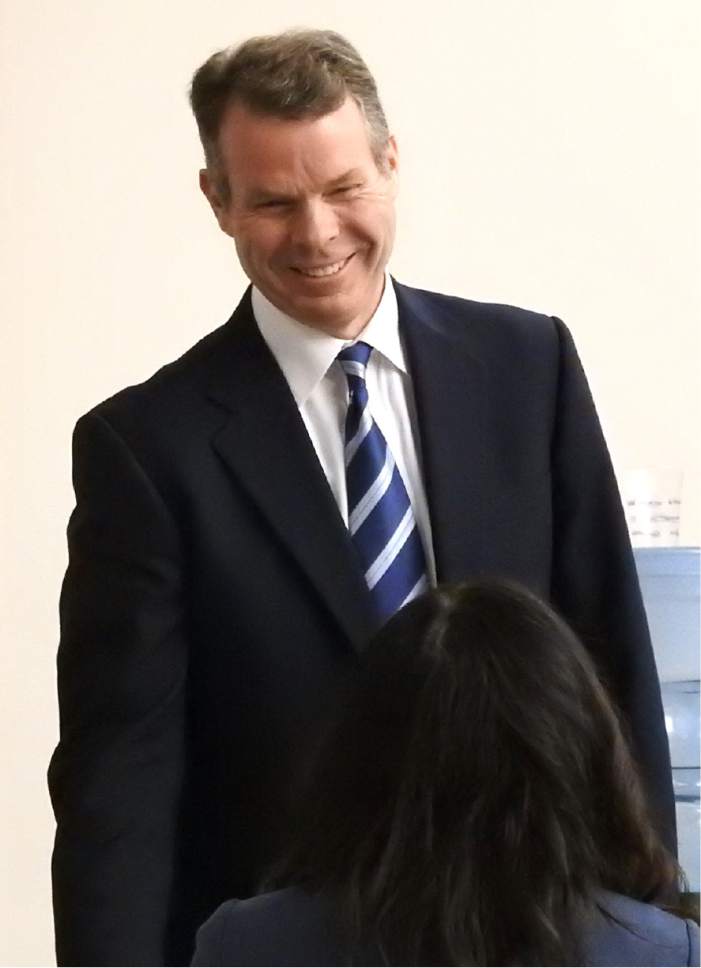

Swallow, who was Shurtleff's handpicked successor, has pleaded not guilty to 13 public corruption-related charges. If convicted, he could go to prison for up to 30 years.

On Day 3 of Swallow's trial, Jenson testified about paying for trips the defendant and Shurtleff took to Pelican Hill after the businessman had reached a plea bargain with the attorney general's office in a securities-fraud case. Jenson still was on the hook for $4.1 million in restitution.

Receipts from the 2009 trips were shown to the jury. They included room charges for things ranging from $5 onion rings to an $84 12-pack of Diet Coke and $240 in souvenirs from the golf shop. Overnight stays in the villas cost roughly $800, Jenson explained, although sometimes the rate was higher.

Jenson, under questioning by a prosecutor, said he also covered expenses for other guests, including several $228 massages for Swallow's wife, Suzanne, when the couple spent their wedding anniversary at the resort.

Williams grilled Jenson about the businessman's recent statements to investigators — that the Shurtleff and Swallow trips weren't about the free villa, golf, meals and other goodies but rather the $35 million in payouts related to what's known as the Whitewater VII FrontRunner station project and securing "protection" from Reid.

Williams asked Jenson, "As a matter of fact, you characterized or agreed today that, in your mind, the key importance of that period of time was a very serious conspiracy and scandal and financial rip-off that was going to occur?"

Deputy Salt Lake County District Attorney Chou Chou Collins objected, arguing the question was irrelevant.

"It's not irrelevant," Williams shot back. "The witness believes that it was the main purpose of the trip and the nub of the conspiracy that was going on."

He pressed Jenson about what he had said about Shurtleff and Swallow at Pelican Hill.

"I believe what I said was Shurtleff and Swallow didn't risk their careers for a few rounds of golf and stays at a villa," Jenson said.

Williams also asked Jenson about a recent interview he had with FBI agents and a state investigator with his attorney present.

"Did they explain to you guys that Greg Hughes and Harry Reid and the resort and Whitewater and UTA 'shouldn't be anything to do with our case?' "

Jenson demurred, saying he would say what he did remember of the interview. When Williams pointed out he was looking at an investigative memo about that meeting, Jenson answered, "Yes."

That line of questioning apparently was designed to fit in with Williams' attack on the state's case during opening statements Wednesday, when he said the prosecution team engaged in an "inventigation" instead of an investigation and argued agents manipulated witnesses and reports.

Williams also delved into Jenson's brushes with the law, including his guilty plea in 1991 to a tax charge and making a false statement to obtain a loan.

In a 1995 case, Jenson entered a plea in abeyance, meaning the securities-fraud charges would go away after three years if he paid $4.1 million in restitution.

Before that plea deal, Jenson said he had been paying Shurtleff's friend and so-called "fixer," Timothy Lawson, tens of thousands of dollars.

Afterward, Shurtleff, Swallow and Lawson, who died last year, started showing up at Pelican Hill, Jenson testified.

Under Collins' questioning, Jenson said he paid tens of thousands in expenses for Shurtleff, Swallow and others for their trips to the seaside resort.

Jenson said he also paid the bills for Utah businessman Mark Robbins, who lived at the resort for much of 2009 and had been involved in the Whitewater VII development. Jenson said he paid restitution to Robbins at Shurtleff's direction.

Jenson also testified that Shurtleff asked him to get one of his employees, Paul Nelson, to intervene with then-U.S. Attorney for Utah Brett Tolman because Shurtleff feared Tolman was getting ready to file charges against him. Tolman and Nelson are first cousins.

Nelson did contact Tolman about Shurtleff, Jenson testified, and Shurtleff later called to tell Jenson he was grateful and that his restitution requirements had been met.

Tolman declined to comment on Jenson's testimony.

Then, in 2011, Jenson was sent to prison for not paying the restitution. The attorney general's office also brought criminal charges against Jenson and his brother related to a failed Mount Holly resort development in Beaver County.

In 2015, Jenson was acquitted in the Mount Holly case and paroled from prison in his 2005 securities matter.

Under cross-examination, Jenson acknowledged holding at least $30 million in assets at the time he owed $4.1 million in restitution.

Jenson said the assets were divided among a $22 million art collection, a $400,000 watch collection and about $8 million worth of equity in four houses — three in Utah and one in Sun Valley, Idaho.

"The state of Utah knew," Jenson said.

Williams asked the witness why he didn't just pay what he owed.

Jenson said it wasn't that simple; there was no ready cash and liens on the assets made them inaccessible.

During cross-examination in the late afternoon and evening, Williams further sought to discredit Jenson by asking about his statements in each of the four interviews he had with the FBI, beginning in 2013, and suggested that Jenson's story had changed.

"Did you tell the truth?" Williams asked.

"I tried to," Jenson said.