This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

A letter carrier opens a mailbox. Inside, he finds a pair of socks, which he unfolds to reveal a .38-caliber pistol and a wallet.

"Sorry," reads a note pinned to the socks. "Here's the gun and wallet taken from the guard at the hospital. I don't want to hurt no one else. I just want to be free."

Ronnie Lee Gardner wrote that note, discovered on Aug. 11, 1984.

Days earlier, the athletic redhead, who would become one of Utah's most notorious criminals, had stolen both items while escaping from a prison guard at Salt Lake City's University Hospital.

Sorry or not, Gardner would go on to murder twice.

Thursday, he will plead with the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole to spare his life, just eight days before he's set to become the first American in 14 years to die by firing squad.

If the execution proceeds, it will end a life of crime that began with petty theft as a child, escalated to prostitution, robbery and assault, and culminated in the 1985 courthouse escape attempt that put a fatal bullet in attorney Michael Burdell's skull and critically wounded bailiff Nick Kirk.

As his scrawlednote — and other acts — plainly stated, Gardner meant to be free. But what if someone got hurt? Gardner never considered that.

As one Utah Department of Corrections investigator put it in 1984: "He always does these horrendous things and then several days later wonders why everyone is so mad at him."

—

Painful upbringing • When Gardner testifies Thursday, he'll speak of helping children avoid turning out like him, sharing a plan to start a Box Elder County farm where troubled youths can learn organic gardening.

"He thinks good, clean living chemical free, that's what kids need," said Tyler Ayres, an attorney helping Gardner and his family finance the farm.

The plan may come off as a ploy to help Gardner avoid the death chamber, but few dispute Gardner knows something about troubled children.

Born on Jan. 16, 1961, in Salt Lake City, he was one of nine children born to Ruth Lucas, a petite woman who drank while pregnant and lived to go out dancing when she wasn't.

Ruth and husband Dan Gardner, a heavy drinker who had trouble keeping a job, split when Ronnie was a toddler, leaving the boy to be mostly reared by a sister eight years older who took over for days at a time while their mother went out partying.

When Dan Gardner was around, he'd tell Ronnie he wasn't his son.

"He hit you. He was just awful," a half sibling once testified.

The family moved around Salt Lake City but always seemed to live in squalor. At age 4, Gardner contracted meningitis. Lawyers and medical experts over the years have argued whether that illness damaged Gardner's brain.

His siblings were a problem, too. Gardner has said an older brother molested him. By the time he was 6, the boy's siblings had taught him to huff gas and glue. At age 10, police investigated a report Gardner had traded a BB gun for marijuana.

Teachers judged Gardner to be hyperactive and said he needed special classes.

"He couldn't learn or he felt like he couldn't learn or he wasn't as smart as the other kids," a brother once testified. "He would get made fun of because he was in remedial classes and he got in a lot of fights over that."

Gardner shoplifted. He prowled for cars to burglarize.

As he got older, his drug use escalated to include methamphetamine, cocaine and heroin. Gardner once told a psychiatrist he would get into a cold tub before injecting meth to mitigate his reaction to the drugs so he could take more.

"I probably injected heroin 200 times," Gardner said, "maybe more."

Already familiar with life in state custody as young as age 9, byhis early teens, Gardner had spent time at the Utah State Hospital in Provo and the State Industrial School in Ogden, then Utah's primary juvenile corrections facility.

And, of course, he tried to escape.

He jumped over fences and swam canals to flee the school, hiding with friends or family before police apprehended him and sent him back.

"I wouldn't stay anywhere — anywhere where I had to be told what to do," Gardner has said. "If somebody let me stay at their place and didn't really boss me around and stuff, we got along fine, but as soon as the rules started coming …I would run away."

Industrial school staffers nonetheless found Gardner to be charming and bright. Worker Stephen DeVries once testified he wanted to open a fruit stand in Jackson, Wyo., and asked Gardner to manage it.

"I had enough trust and faith in him," DeVries said.

But the plan fell through.

—

Father issues •The few men a young Gardner viewed as role models only encouraged his criminal tendencies.

Siblings said he idolized his mother's subsequent husband Bill Lucas, serving as a lookout while the man burglarized homes from Parleys Canyon to Wyoming.

Lucas stole mercury from gas meters to sell and brought it home in Mason jars. Gardner and his siblings played with the toxic gray balls, rolling them along the dirty floor.

Lucas spent 1968 in the Wyoming State Penitentiary for grand larceny.

Later, when Gardner was a young teen, a brother met Jack Statt at a bus stop and agreed to perform oral sex for $25. The brother, and eventually Gardner, ended up living with Statt, who even became Gardner's official foster parent for a few months in 1975.

Statt performed sex acts on the boys. Gardner also later admitted to psychologists that he worked as a prostitute while living with the man. Those psychologists called Statt a pedophile, but Gardner has said his time with Statt was the most stable of his life and one of the few times somebody seemed to care about him.

"Jack was a good man, and he tried to help us out," Gardner said.

—

New family • Gardner met another who seemed to care for him when he was 15 and briefly out of state custody.

A teenage Debra Bischoff lived in the same Salt Lake City complex as Gardner's mother and found herself drawn to his athletic build, red hair and wide grin.

"He was very nice," Bischoff said in a telephone interview. "Very caring. He never put me in the rough situations he was in throughout his life. He sheltered me from that stuff."

Bischoff got pregnant, and in May 1977 gave birth to Gardner's first child, a daughter.

By then Gardner was back in custody, but Bischoff remained committed to him for seven years. They lived together when Gardner was not in the industrial school or in jail.

Finally freed from custody in 1979, Gardner planned a second child with Bischoff. He was there for the February 1980 birth of their son.

The same month the boy was born, Gardner, then 19, entered the Utah State Prison for the first time, convicted of robbery.

"It broke my heart," Bischoff said. "At that point, I really loved Ronnie."

—

Shot in the neck • As a prisoner, Gardner's criminal reputation flourished.

Just months after his incarceration in a minimum security unit, he obtained some amphetamine tablets, got high, and with another inmate, climbed over the Draper prison's fence to escape.

Bischoff had slept with another man while Gardner was in prison and feared Gardner would come looking for her.

He did.

"We had a talk about a few things," Bischoff said, "and it was an emotional time for us because I told him how I felt when he went to prison. It was the first time I'd ever seen Ronnie cry."

The next few days would be the last time he would spend with Bischoff and their children outside prison.

Gardner took a gun and went to South Salt Lake to confront the man with whom Bischoff had slept. The man fired a .22-caliber bullet into Gardner's neck.

Police captured Gardner as he tried to hitch a ride away from the scene. He earned more time in prison for the escape and other crimes he'd committed while on the loose.

He tried escaping twice more, getting caught the first time between two security fences, but succeeding on Aug. 6, 1984, after faking an illness and attacking the guard at University Hospital. Gardner punched Don Leavitt hard enough to shatter an eye socket and break his nose in 16 places. Doctors had to wire Leavitt's entire face.

Outside the hospital, Gardner jabbed Leavitt's pistol into medical student Michael Lynch's forehead and ordered Lynch to take him on his Yamaha to an apartment complex, where he stole the student's clothes and tied him up with his own shoelaces.

On the run, Gardner turned to his family for help. His only full-blooded brother put the gun, wallet and note in the mailbox for police to find, not wanting them to think Gardner still had the gun.

—

First killing • Murder remained about the only crime for which Gardner had not been convicted, but not for long.

High on cocaine on the night of Oct. 9, 1984, he went to Salt Lake City's Cheers Tavern with Darcy McCoy, the sister of a cousin's wife, intent on robbing the place, according to McCoy.

Melvyn Otterstrom, a 37-year-old comptroller tending bar to earn extra money, was on his back behind the bar when Gardner pressed the muzzle against one of his nostrils and fired, killing him.

Gardner has complained Otterstrom fought back when robbed, but investigators found nothing to suggest the larger and special forces-trained Otterstrom put up a fight, said John Johnson, the Salt Lake City police detective who investigated the murder.

"My opinion is, it was an execution," Johnson said.

Three weeks later, police acting on a tip arrested Gardner at a cousin's home.

Gardner was charged with first-degree murder and other escape-related felonies. Gardner knew he would never be released from prison. He considered his options.

"One was escape," Gardner testified later. "The other was possible suicide if I had to spend the rest of my life in prison."

He chose escape.

—

Infamy arrives • Gardner has never divulged his accomplices, but on April 2, 1985, two prison guards escorted Gardner to a hearing at Salt Lake City's Metropolitan Hall of Justice. A woman thrust a gun at him and Gardner turned, pointing the weapon at the guards.

One guard, Luther Hensley, said it appeared Gardner was trying to shoot him but couldn't get the gun to fire. Hensley drew his .38-caliber pistol and fired one bullet into Gardner's upper right chest.

Gardner took cover behind a Coke machine, then retreated a few feet away to the courthouse's archives room. After exiting the room and trying to board an elevator, he fired at Michael Burdell. The bullet pierced the attorney's right eye.

Burdell said, "Oh, my God," and collapsed. He died at Holy Cross Hospital about 45 minutes later.

Nick Kirk, an unarmed bailiff, ran toward the room worried about the safety of the judge for whom Kirk worked.

Gardner fired another shot, striking Kirk in the lower abdomen. By then, dozens of police officers had converged on the courthouse as Gardner attempted a frenzied escape.

He had made his way to the sidewalk between the street and the complex when they drew their guns and moved toward him.

But Gardner surrendered before they reached him. He threw the revolver away, dropped to his knees and fell face first into the grass.

"Don't shoot," Gardner yelled. "I don't have a gun."

—

'The crazy bad guy' • Just 24 years old, Gardner's convictions seemed a forgone conclusion. In June 1985, he pleaded guilty to Otterstrom's murder and received life without parole.

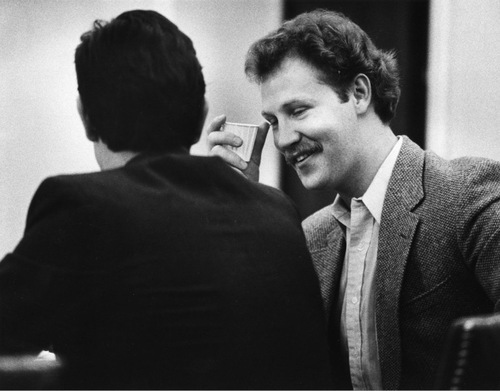

On Oct. 22 of that year, a seven-woman, five-man jury deliberated just three hours before convicting him of capital murder in Burdell's death.

Gardner had been smiling and cheerful throughout the trial but grew serious after the verdicts were read.

"He wasn't surprised," defense attorney Andrew Valdez told reporters that day.

The jury sentenced Gardner to death three days later. His cousin's wife spent eight years in prison as his accomplice in the courthouse escape.

In the 25 years since, Gardner has been a consistent problem for guards.

On Oct. 28, 1987, Gardner broke a glass partition between inmates and visitors and he and other inmates barricaded the doors. Gardner and his female visitor had sex while other inmates in the room watched and cheered.

On Sept. 25, 1994, Gardner got drunk on alcohol he fermented in his sink. He took a shank made from a pair of metal sunglasses and stabbed a black inmate in the neck, chest, back and arms.

The stabbing occurred two months after a white supremacist stabbed a black inmate to death at the Gunnison prison. Kevin Nitzel, who investigated Gardner's stabbing for the Utah Department of Corrections, thinks Gardner wanted to steal the spotlight.

"Ronnie Lee likes to play up his image of being the crazy bad guy," he said.

For the stabbing, prosecutors charged Gardner with another capital crime under a little-used Utah law reserved for attacks in prison. But three years after the stabbing, the Utah Supreme Court determined Gardner could not be charged with a capital offense for an attack in which no one died.

—

'I am burnt out' • Gardner's behavior has earned him harsher treatment than most of Utah's 10 death-row inmates.

Eight are allowed out of their cells to recreate for up to three hours a day. Gardner and Troy Kell, who was convicted of the fatal stabbing at the Gunnison prison, are allowed out of their cells for one hour every day and live in a different section of the Draper prison.

At least three times, Gardner has said he wants to stop appealing his sentence. He's tired of his near-solitary confinement and the pain from ailments his attorneys have said include rheumatoid arthritis, hepatitis C and leukemia.

"I am burnt out. I can't deal with it anymore," Gardner said at a hearing on Sept. 17, 1999. "Eventually what is going to happen is the prison is putting me in predicaments where I am going to end up killing somebody else."

But every time, his lawyers have persuaded him to continue appealing. In this week's hearing, Gardner will ask the board to lessen his sentence to life without parole. If the board refuses, it will take a surprise order from a court to stop the June 18 execution.

Bischoff and their children have maintained contact with Gardner over the years. Gardner has three grandchildren, she said.

He's made other friends over the years, too.

Robert Macri, an attorney who was with Burdell in the courthouse archives room and testified against Gardner in 1985, began visiting Gardner in prison. Marci in 1999 said he taught Gardner grammar, yoga and about King Arthur and chivalry.

A book Gardner read about organic gardening sparked his idea for the farm, which Ayres said would accept children with legal or substance abuse problems.

Gardner's brother acquired the 160-acre lot in north of the Great Salt Lake. It is vacant and undeveloped.

Ayres said Gardner has written to Oprah Winfrey and others asking for donations to start the farm. He doesn't know how Gardner's execution would affect fundraising.

Ayres, who also helped Gardner write his will, said the man is sincere in his wish to help children.

Although it's unlikely since Gardner is in maximum security, Ayres said Gardner would try to escape again if he had the chance. "He knows how to look for those opportunities."

In addition to interviews, sources for this story included transcripts of Ronnie Lee Gardner's 1985 trial, court opinions, appeal proceedings and a deposition Gardner gave in 1999.