This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

For most of Kevin Jones Giddins' 55 years, his family history was a blank slate, save for a name on an aging birth certificate: Jacqueline Deborah Giddins.

"She was 15 when she delivered me. Her mother insisted she give me up to a foster/adoption agency. At the time, in the early 1960s, she just wasn't prepared to raise a child," explains the Orem time-management consultant, entertainment entrepreneur and Mormon.

After years of foster care in New York, he became one of 11 children reared by a New Jersey African-American couple. It was a loving, churchgoing family Giddins still treasures — but while he had been born in the hearts of Edmond and Elizabeth Jones, his own bloodlines remained a mystery.

Then, for Giddins' birthday, a friend gave him an AncestryDNA test kit. He put the $99 gift on the shelf and forgot about it.

"One day, in spring 2016, I took it down and looked at it. I thought to myself, 'I should take this thing. I've been looking for my mom all this time,' " Giddins recalls. "So, I did it. I took the test."

Using the kit's prepaid packaging, Giddins mailed a sample of his saliva to AncestryDNA for analysis of maternal and paternal genetic information ("autosomal DNA," or all 23 pairs of chromosomes). A few weeks later — it can take six to eight weeks — he was notified that his results were available online.

"They give you links to everyone [in the testing database] you share DNA with," Giddins says. "I found my mom and much more. I found a brother, two sisters, cousins, aunts and uncles. I found my history; I found my truth."

Giddins' biological mother, now 70 and living in Columbia, S.C., called him, knowing only that her family tree indicated that they somehow were related. As they talked, she asked for his birthday.

"Dec. 17," he answered.

"She said, 'I am the woman on your birth certificate.' We both cried," Giddins says. "She told me that on every Dec. 17, she had prayed to God that I was well."

Giddins, his wife, Lita, and their five children have since visited his rediscovered relatives in South Carolina, and he talks with his biological mother two or three times a week on the telephone.

"We have a lot to catch up on," he laughs.

Spokeswoman Crista Cowan said that while Lehi-based AncestryDNA provides clients with ethnicity breakdowns, it does not keep specific records of customers' race or religion. That said, there seems ample anecdotal evidence (a search of YouTube using the term "African-American DNA testing" turns up more than 40,000 results) of black people using AncestryDNA and other testing companies to plumb their roots.

"A lot of people are creating videos of their DNA 'reveals,' " Cowan says, adding that many customers are surprised at the ethnic diversity discovered within their chromosomes.

Overall, AncestryDNA has seen orders for its kits skyrocket since the service launched in May 2012. More than 3 million people have tested, with that number having jumped from just 2 million in spring 2016.

As life-changing as DNA testing has proved for African-American clients in general, it allows blacks who have embraced Mormonism to do what other Latter-day Saints take for granted — identify ancestor candidates for baptismal temple rites for the dead.

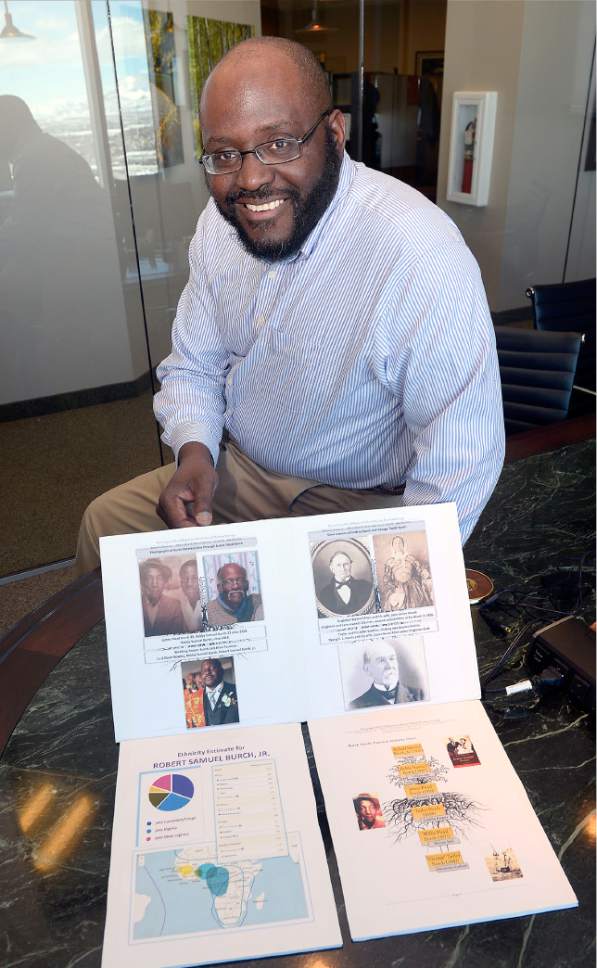

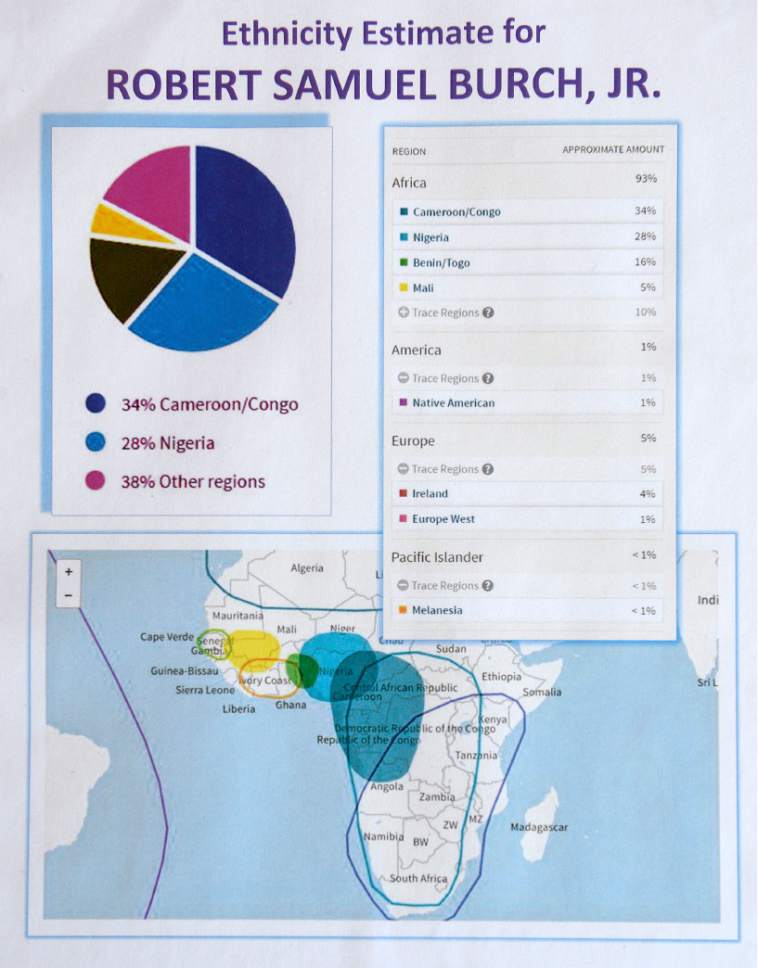

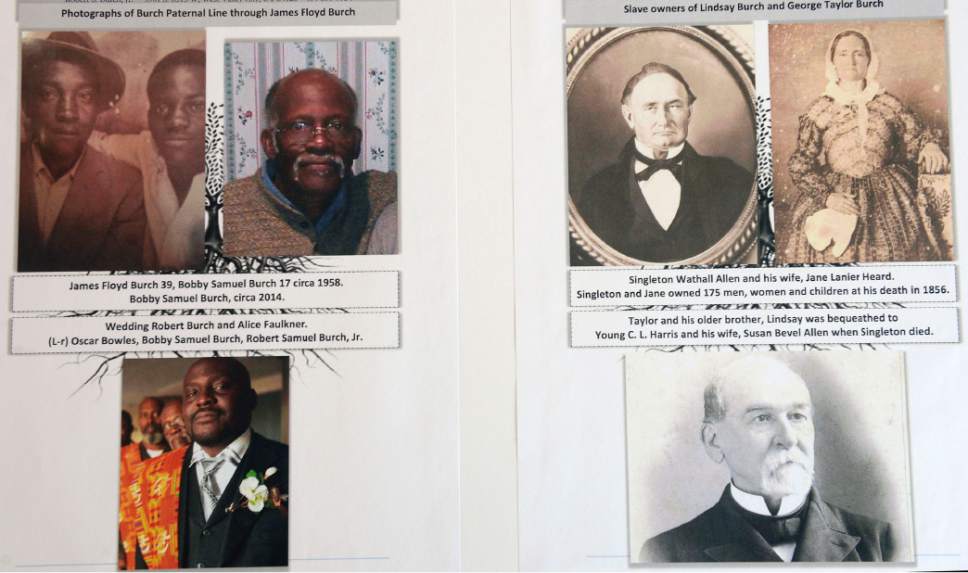

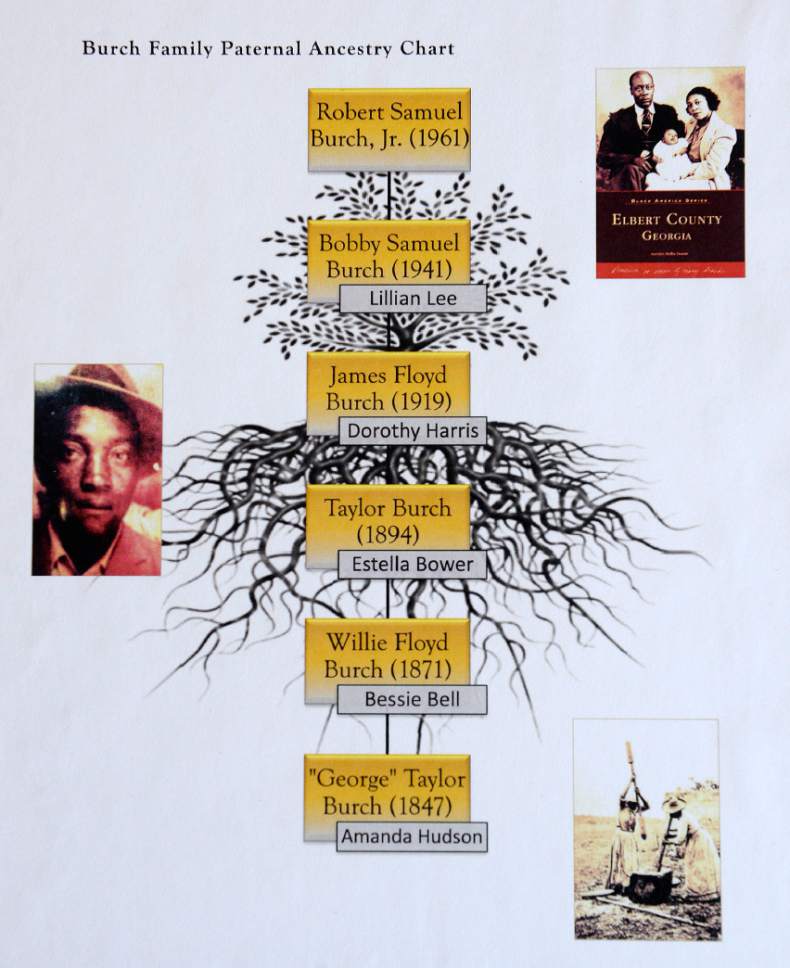

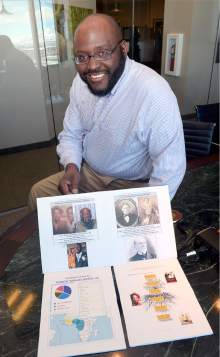

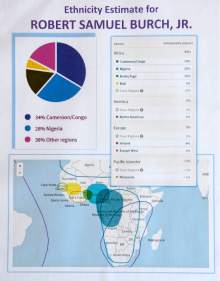

Robert Burch Jr., president of the Utah chapter of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, found DNA results in 2016 that took him beyond his slave forebears, all the way to ancestors in the Cameroon and Congo regions several centuries ago.

"I encourage African-Americans to do DNA testing," Burch says. "It allows us to leap across the obstruction of 600 years of racial lies and historic deletions."

Darius Gray, former president of the Genesis support group for black Mormons and a frequent speaker on African-American genealogy, says his DNA test results not only shed light on his origins, but also on the common roots of all human beings.

"I am a blend of several ethnicities, first and most proudly African-American," Gray says, "but also Native American on my mother's side and [on his father's side] the British Isles."

There were some surprises, too. He learned he has strong ethnic links to Mali and the Bambara tribe — and some Jewish DNA.

Giddins not only has been able to trace his roots back to slave ancestors on the John Giddins plantation in Virginia (that Giddins also was a biological great-grandparent), but also to Africa itself. Indeed, his DNA ethnicity was 85 percent African — specifically from Cameroon, Benin-Togo and Ghana.

To Giddins' surprise, he learned he, too, is part Jewish.

When he was baptized into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints years ago as a Brigham Young University student, Giddins says he received a blessing declaring to him that "the blood of Israel flows through your veins."

"I wondered how, as a black man, that could be," he recalls. "Now, my DNA results turn out to have confirmed that."

Twitter: @remims How DNA testing works

Numerous DNA testing services are available, many offering Y-chromosome- based sampling to determine paternal ancestry or mitochondrial (maternal) ancestry.

AncestryDNA's kit uses autosomal DNA testing, maintaining that it is more comprehensive and surveys a person's entire genome.

Autosomal DNA testing services — also offered by 23andMe.com, familytreedna.com and others — generally involve providing either a cheek swab or saliva in a tube that is then shipped to a cooperating laboratory. Costs can range from $79 to as high as $199, depending on the provider.

Results and DNA connections typically are provided through websites or email.