This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Logan • The newly opened diary of Leonard J. Arrington, Mormonism's most influential historian of the late 20th century, reveals a life imbued with the sense that he was chosen by heaven to help the LDS Church and its people truthfully tell the Mormon story.

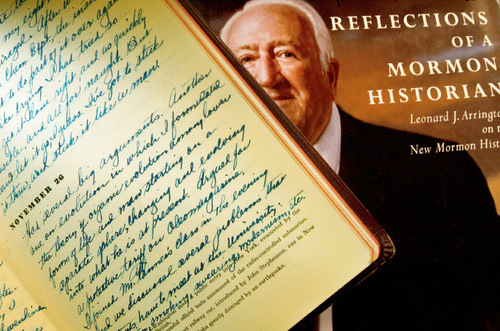

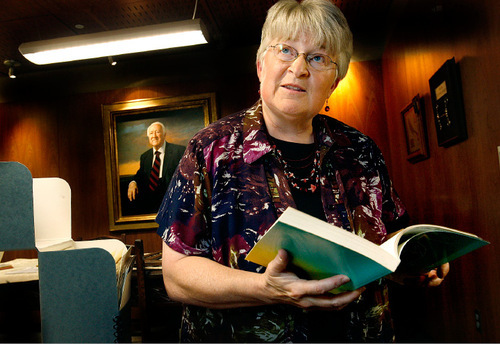

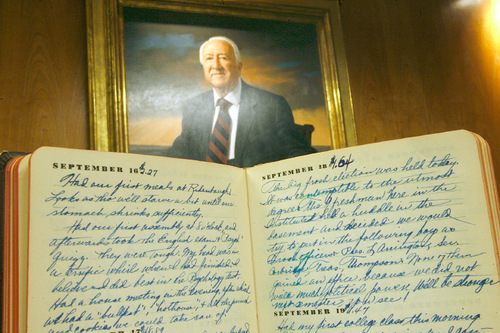

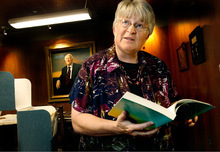

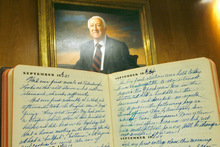

The diary — or, more precisely, the scrapbook — fills 50 boxes at Utah State University's Special Collections and Archives, where it was sealed for a decade after Arrington's death in February 1999.

Thursday's annual Arrington Mormon History Lecture, to be delivered by two of the late historian's three children, marks the official opening of the diary.

The diary is not a juicy trove of gossip from the man who presided over The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' aborted attempt at a professional church history division in the 1970s. Nor does it dwell on Arrington's disappointment with the leaders who pulled the plug.

Rather, historian Ronald W. Walker says, the diary is "an annal of the intellectual life."

"It's an extremely important historical document in terms of life, letters and thought in the 20th century," says Walker, who worked in the historian's office under Arrington.

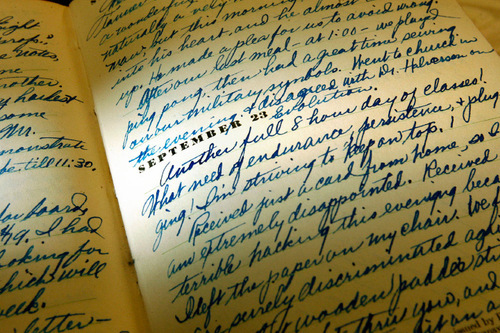

For Arrington's children, the opening is a chance to tell about the father they loved — and understand even better after surveying his 30,000-page diary, including thousands of pages he pounded out on a manual typewriter as well as miscellany such as opera programs, birthday cards and, tellingly, yearly photocopies of his LDS temple recommend, signifying faithfulness to the Utah-based church.

"We're focusing on Leonard Arrington, the man," son Carl Arrington says. "He spent half his life living and the other half writing down what it was he lived."

The gregarious historian mentored hundreds and had 5,000 people on his Christmas card list, Carl Arrington says, but few knew much about his early years as an Idaho farm boy.

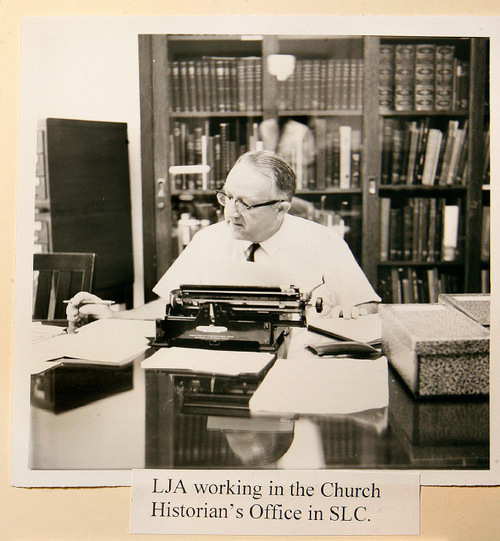

Nor did they necessarily realize that when they chatted with Arrington, he would type long into the night, recording the conversations for posterity. His children remember light from under the door of his office in the wee hours, the sound of his fingertips tapping on keys.

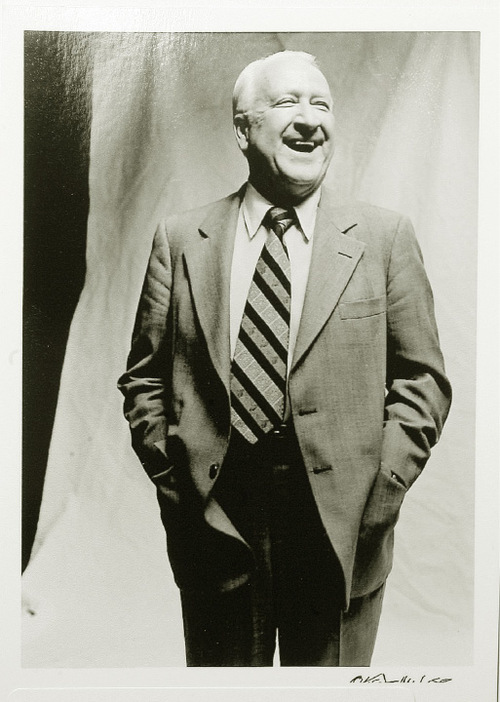

"He was something of a sphinx," Carl Arrington says. "There was a brilliant mind there at work, even though when you were talking to him, he just seemed like a guy ... who was interested in what you were saying."

Arrington's humor, his son adds, was not always evident in his scholarly writing. He liked puns and often saved jokes for the family dinner table. Peeved by secretaries who asked his name when he telephoned their bosses, he would claim the name of a long-dead U.S. president – Grover Cleveland.

"Some of the stories we have," Carl Arrington says, "are every bit on the level of James Thurber and Woody Allen."

—

Survivor • Arrington's conviction that he was chosen for a special work began early in his life, daughter Susan Arrington Madsen says.

He was born July 2, 1917, and reared on a 20-acre Idaho farm near Twin Falls by parents who were LDS converts.

By age 4, Arrington had survived typhoid fever, smallpox, pneumonia and the deadly flu epidemic of 1918-19. His mother — who had helped a nurse anoint him with consecrated oil (commonly used by LDS male priesthood holders in blessings) during his bout with flu and pneumonia — instilled the notion that he was spared for a reason.

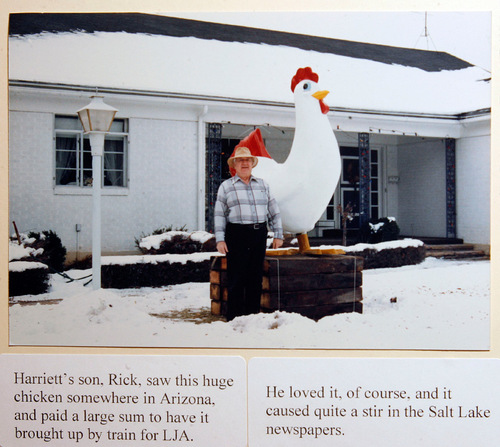

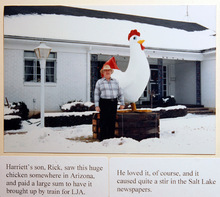

Arrington, the third of 11 children, began recording his life at age 10 and showed an entrepreneurial bent by raising chickens to feed and make money for the family. Later, the chicken would be the self-effacing Arrington's mascot; it adorned his stationery and his lawn in the form of a supersized Fiberglas bird.

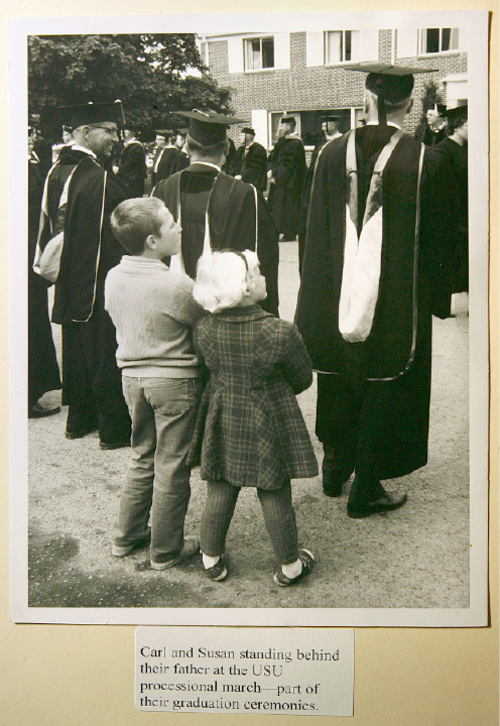

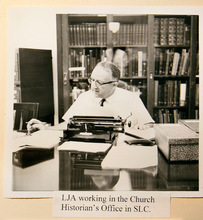

The young scholar earned a bachelor's degree in agricultural economics at the University of Idaho and met his bride, Grace Fort, while a graduate student at the University of North Carolina. The couple settled in Logan after he served three years in the Army during World War II. He taught at USU for 26 years and, after his church history stint, for five years at Brigham Young University.

In 1950, while finishing his doctorate in economics at North Carolina, Arrington had what he called a "holy, never-to-be-forgotten encounter" that confirmed his belief that God wanted him to "carry out a research program of his peoples' history," according to his 1998 memoir, Adventures of a Church Historian.

—

'Cried all the way' • Grace Arrington, according to son Carl Arrington, is the "unsung hero of Mormon history because she made it all possible," rearing the children — James, Carl and Susan — and maintaining the home and yard while Arrington devoted himself to work.

Both were thrilled when Arrington, in 1972, was named the church's first professional historian in the newly organized Church History Division. But Grace "cried all the way from Logan to Salt Lake City" when they moved, Madsen says. She already missed her friends and the Logan home she had designed.

Grace Arrington suffered, the siblings say, as she watched some in church leadership undermine the historical endeavor and her husband. He was replaced unceremoniously as church historian in 1980, but still managed the history division.

"My mom absorbed a huge amount of pain from all that," Carl Arrington says. Depressed and suffering from heart disease, she died three weeks before the history division finished moving to BYU in 1982.

"He [Arrington] maintained a cheerful countenance ... even as the ship was sinking," Carl Arrington says. His diary does note, however, a "final indignity." Arrington's requests for new carpet long had been rejected, ostensibly for lack of money. The day after he vacated the office, carpet-laying crews arrived.

"Our great experiment in church-sponsored history has proven to be, if not a failure, at least not an unqualified success," Arrington wrote in his diary. " ... One aspect that will be personally galling to me will be the gibes of my non-Mormon and anti-Mormon friends: 'I told you so!' "

Arrington remarried in late 1983 Salt Lake City resident Harriett Horne.

Madsen says that, although the diary includes some rich nuggets that will interest researchers, her father did not record history "warts and all."

"He had this wisdom," she says. "He was cautious what he put in there [the diary] because he knew it would be read."

—

His legacy lives • Jan Shipps, an eminent non-Mormon scholar, sees his fingerprints on the LDS Church's increasing openness to scholarship in the past decade.

She cites the enormous resources the church put into the five-story Church History Library in downtown Salt Lake City and the publishing of The Joseph Smith Papers. The church's cooperation with Walker and his two co-authors on the 2008 history Massacre at Mountain Meadows, is another example.

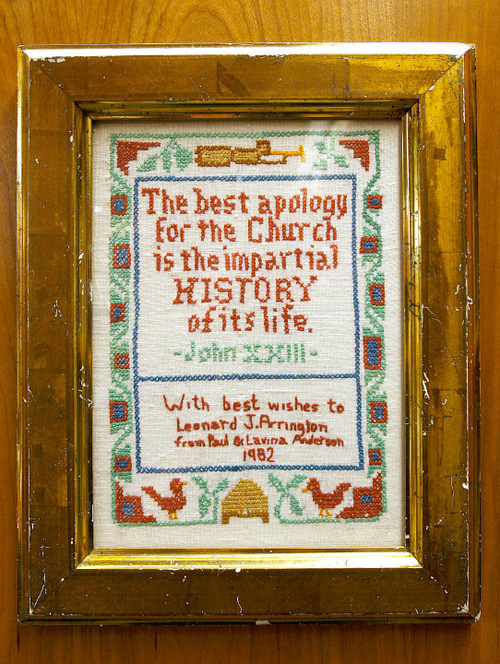

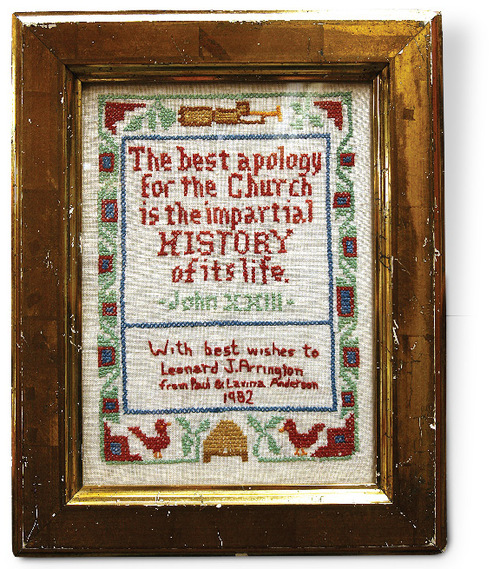

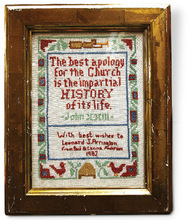

"Now, people at all kinds of institutions are studying Mormonism and it really is a change," Shipps says. "I don't think it would have happened if you didn't have that period when Leonard said history has to be told how history should be told."

Walker agrees. "It's a product of a generation of church leadership that understood that honest inquiry is not incompatible with faith."

Arrington's children say their father would be happy with recent developments.

"He won a few battles. He lost many more. But, finally, he's won the war," Carl Arrington says. "If he is looking down, and I'm sure he is, he's smiling from ear to ear."

About the lecture

Two of Leonard Arrington's children will deliver this year's Arrington Mormon History Lecture, the 16th annual lecture in the series bearing the historian's name.

Hyde Park resident Susan Arrington Madsen and New York's Carl Arrington will deliver "A Paper Mountain: The Extraordinary Diary of Leonard James Arrington" at 7 p.m. Thursday at the Logan LDS Tabernacle, 50 N. Main. The free lecture is sponsored by Utah State University's Special Collections and Archives.

Arrington donated his personal papers and historical collection to USU upon his death in 1999 and directed that his diary be locked away for a decade. Thursday's lecture is the formal opening of the diary to the public. —

Who was Leonard J. Arrington?

Leonard Arrington was an Idaho farm boy who became a leading LDS historian before dying at age 81 in 1999. He is considered, along with B. H. Roberts in the early 20th century, as one of the LDS Church's two most influential historians.

Author • He wrote or co-authored 36 books and dozens of articles and essays. His 1958 book, The Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, is considered his best, while his biography Brigham Young: American Moses and his memoir are popular as well.

Historian • He was the first professional to be appointed church historian, in 1972, but watched as church leaders dismantled the history division and moved it to Brigham Young University within a decade.

Founder • He was a founder of the Mormon History Association, an advisory editor of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought and encouraged hundreds of scholars through personal letters.

'Beloved mentor' • Arrington is buried in the Logan Cemetery next to his first wife, Grace, who died in 1982. Of all his accomplishments, his children chose one to be etched on his gravestone. It reads "beloved mentor."

– Kristen Moulton —

From his diary

On general conference • "The women presidencies ... sit near the front on the farthest right side facing the stand. Why couldn't those sisters be placed in the center, behind the regional representatives and in front of stake presidents? Why do they have to be shunted over to the far right? Or, why not find a place for the three presidents — Relief Society, Young Women and Primary — on the stand or front row? Another thing that must seem peculiar to some observers is that all of the special guests on the first two rows all the way across the Tabernacle, are men. Don't we ever have any special guests who are women? If not, why not?"

On Benson's 'blacklist' • Arrington spoke Italian and loved all things Italian. An advisory editor of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, he once was poised to be called as president of the Italy Mission when an article appeared in the journal that offended then-apostle Ezra Taft Benson. "The article was not friendly. I knew it would cause trouble. It did. Seeing that my name was connected with a publication so anti-church, as Elder Benson viewed it, he removed my name from the call, and from that time my name has been on his blacklist."

On the history division • "Our great experiment in church-sponsored history has proven to be, if not a failure, at least not an unqualified success. … One aspect that will be personally galling to me will be the gibes of my non-Mormon and anti-Mormon friends: 'I told you so!' "