This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

For five months, the offensive coordinator of the Eastern Washington football team lived alone, sleeping on a mattress in the dining room of a mostly empty house.

The set-up was about convenience: Troy Taylor could reach the light switch and the thermostat from his bed, then walk into the kitchen when he was hungry. Other aspects of life in Cheney, Wash., were more complicated.

"I was trying to steal my neighbor's Wi-Fi, but that didn't work out," he said. "That was pretty depressing."

Eight hundred miles away, his wife and three children were living in a house that wasn't selling — a problem, since Taylor had taken less money to move back into the college coaching ranks after 13 years building a Sacramento high school powerhouse.

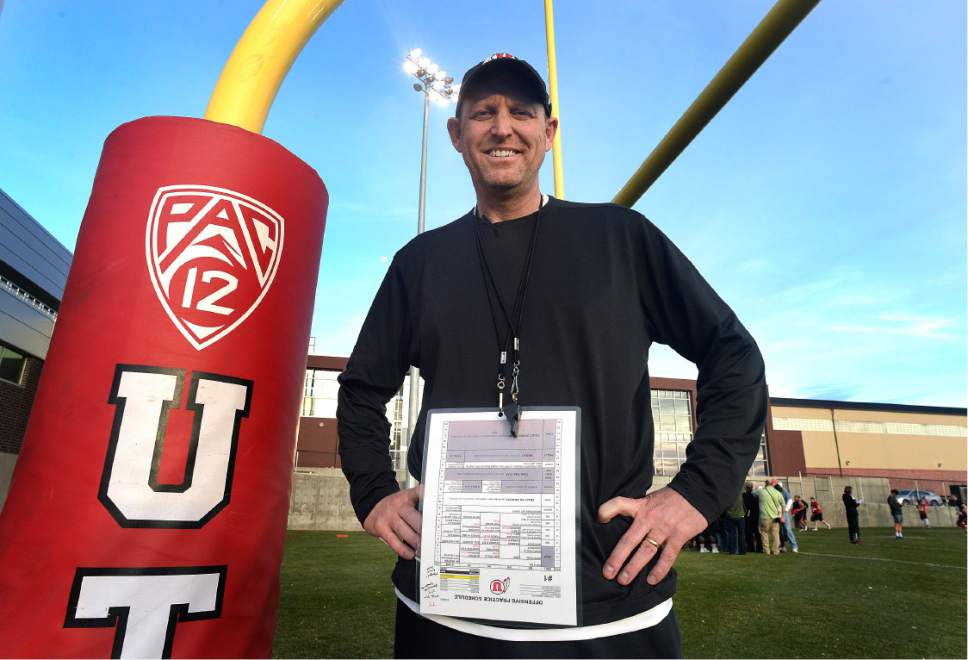

This year, Taylor, 48, will overhaul Utah's offense with an up-tempo scheme and fearless play calls. But no play he's drawn on his volumes of legal pads will be bolder than the gamble he took on himself and the offensive system he believes in.

"I'm just going to try to be me, because that's the only chance I really have to be successful," he said. "I'm going to bring my energy, positive enthusiasm, cutting it loose, trying to build quarterbacks' confidence and being dynamic. Hopefully it's good enough."

Building a philosophy

Here are a few things others observe about Troy Taylor: He's a doodler, constantly scribbling and drawing up plays on legal pads. He'll talk football with anyone; 20 minutes into this interview, he is showing play diagrams in his office, drawing on his TV with erasable marker. He's not one to rip players in practice: He prefers the positive, build-you-up aspect of coaching.

"At the end of the day, we're all coaches, and we have a bit of fire to us," said Utah running backs coach Kiel McDonald, who coached with Taylor at Eastern Washington last year. "But he's positive. He wants everything to be positive. He's not one of those coaches who goes old school, dog cussing you a little bit."

These were all characteristics Taylor developed over a career that spans more than two decades, finding the best version of himself.

As Taylor explains his offense, it's apparent that everything in it has a purpose. The quarterback progressions are designed to allow the passer to look at every receiver in one sweep of the head, and motion to one side of the field helps shift defenses away from where the progression is going. The tempo is designed to wear defenses out. The option routes are designed to give receivers the ability to find open spaces.

Taylor didn't learn that at Cal or Colorado, where he says he copied plays he liked and tried to emulate others. It wasn't until he was at Folsom High in Sacramento, after he and his wife decided to settle down, that he started putting thought into what he wanted in his own system.

That isn't to say he didn't borrow concepts: He visited schools across the West to observe practices of coaches he admired — Chris Petersen at Washington, Chip Kelly at Oregon, Mike Leach at Washington State. He incorporated their schemes but built a cohesive offense that was his own.

"I had to figure out a way to be successful with not necessarily the most talented guys," he said. "I think it drew out my best ability to coach. Then we started getting better talent, and that changed. I believed things when I was younger that I take a completely different view now. That's experience."

Under his guidance and along with his co-head coach, Kris Richardson, Folsom became known for its dynamic passing attack, shattering state and national records with plays called in 13 seconds or less. Between 2012 and 2015, Folsom went 58-3.

His success was noticed in the college ranks.

"Even before he came to Eastern Washington, I had known Troy for two or three years and knew the mind he has," McDonald said. "I believe his confidence comes from years of learning and years of seeing his scheme work. He's in that one place for years and years, and it just allowed him to continue to work and process through what he wanted to do."

Risky business

The thing about winning consistently at any level, from high school to the pros, is once you do it, the bar starts to get higher.

That happened at Folsom, as Taylor's teams won two state titles in four years, and built a 40-game winning streak at home. A Bulldogs loss was rare, but when it did happen, it felt like an enormous letdown. Both Taylor and his wife, Tracey, started to get restless in Sacramento.

"I needed a new challenge," he said. "It was time to do something else."

Taylor mentioned offhand to Petersen one day that he would get back into college for the right situation. That situation arose when Eastern Washington looked to replace an offensive coordinator; Petersen called up EWU coach Beau Baldwin, telling him he might want to check out Taylor for the job.

Taylor's interview went well: He called him and offered him a job soon after. But the salary, which Taylor knew ahead of time would be low, was an issue. He would make half as much as EWU's coordinator as he did as a head coach and teacher at Folsom.

"The look in my wife's face, I'll never forget it when I told her the salary," he said. "It was, 'How are we going to live?'"

Their anxieties over money seemed well-founded for a while. As Troy moved to Cheney for spring football and Tracey stayed in Sacramento to finish the school year with the children, they put the house up for sale. It took a while to move. Taylor said he had to borrow money from a friend at one point.

Finally, it did sell. The Taylors all moved to Cheney, with the family filling up what had been a bachelor pad.

"It's funny, when you have kids, there's so much noise — it's kind of like a circus," Taylor said. "But when you get away from it, you miss it immediately. It was good to have everyone in one place."

The on-field results, as Taylor expected, took care of themselves. In his first game calling plays, Taylor helped orchestrate a 45-42 upset over Washington State, which Utah coach Kyle Whittingham said caused him to take notice of Taylor. Eastern Washington led FCS in passing yards behind first-year starter and former walk-on Gage Gabrud.

"Once coach got rolling, I think it just all kind of fit," McDonald said. "Maybe it was the right time. He didn't take long to get acclimated at all."

Next challenge

His new job at Utah pays a lot more than his last, and thus was an easier sell to his family. But nothing illustrated the difference between Big Sky and Pac-12 budgets like when Taylor asked if he could get a slightly bigger television for his office. A 70-inch screen now takes up most of one wall in his office.

"It's kind of embarrassing," he said, gesturing to the monitor.

But the work is the same. Taylor spends most of his time in his office, diagramming plays as he always has. He tries not to rely too much on playbooks — "the most overproduced and underread document in the world" — but does a lot of work with video and mental reps to get his quarterbacks ready for action.

Some of his traits rub off.

"I doodle plays now — as a matter of fact, I was doodling this morning before practice," McDonald said. "But I think honestly the biggest impact that Troy probably had is the positivity piece. Not all coaches have that gene in them. I've modified my coaching style a little bit."

Whittingham has praised Taylor's attentiveness to detail both publicly to the media and privately to athletic department officials. Utah's quarterbacks all seem to be open to change.

"Coach Taylor just wants to make it as simple as possible," quarterback Troy Williams said after the first spring practice. "We can just go out there and play and not think about anything else."

For Taylor, the game is the only thing he has to worry about. His salary is estimated to be well into six digits, and his children have enrolled in Salt Lake City schools. His house is four minutes away from the football facility.

While Taylor declined to comment, a source close to the program confirmed that he turned down an offer to return to Cal, his alma mater, soon after he took the Utah job. The Golden Bears went on to hire Baldwin, Taylor's old boss.

It's interesting, he admits, that the Pac-12 is set up for comparisons. He'll have to coach against his old Folsom quarterback protege Jake Browning at Washington next year, and the Baldwin-Taylor offensive comparisons seem inevitable.

"For me, I will root for those guys every other day except when we play them," he said. "You just keep your focus on what your task is. But you want to beat your friends more than anybody, right?"

Twitter: kylegoon