This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

St. George • In one case, a dinosaur's thumb claw was thought to be a horn. In another, the fossilized skull of a dinosaur was mistakenly placed at the tip of its tail.

In paleontology, bloopers happen.

A new exhibit at the Discovery Site museum in St. George explores some myths and mistakes in the context of the history of paleontology. "Dino Right, Dino Wrong," open through March 1, was the brainchild of Rusty Salmon, director of the dinosaur track site discovered in 2000. The museum houses fossilized tracks and even slither marks left by creatures that inhabited the shores of Lake Dixie 198 million to 195 million years ago.

"What we want [for the museum] are temporary exhibits showing things people are interested in," said Salmon "This idea just bubbled up."

She said special activities are planned Wednesday for National Fossil Day.

The new exhibit includes several examples of how conclusions drawn by early paleontologists were later proven wrong as identification techniques improved and knowledge increased.

"They [early scientists] had some pretty quirky ideas," said Salmon.

Besides misidentifying the thumb claw, scientists wrongly believed the tail of the spine of elasmosaurus was the top of its neck and worthy of a fossilized skull. They stood by their claim until it was proved that the other end of the long spine was where the head really belonged.

Other "dino wrong" trivia has to do with names.

"One dinosaur named syntarus in 1869 had to be renamed after it was realized the name had already been given to a beetle," said Salmon.

Anyone who believes that birds are direct descendants of dinosaurs, however, is "dino right." The exhibit offers an elaborate fossil that supports the current theory.

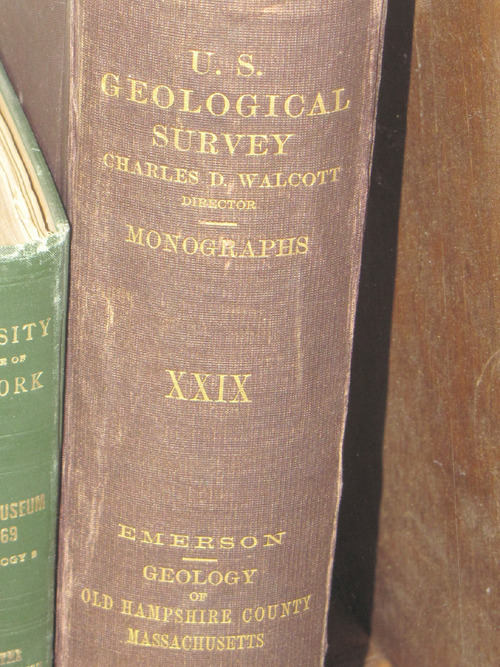

Also on display are early geology textbooks along with toy dinosaurs and novels featuring the giant creatures, including The Lost World and Jurassic Park, which were later made into popular films.

Salmon said the movie Jurassic Park took artistic license by portraying a poison-spitting lizard as much smaller than it was. And its velociraptor, the human-sized meat eater that terrorized the film's characters, was really rather puny compared with a person, said Salmon.

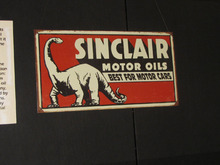

Displays also feature signs and posters bearing the logo of Sinclair Oil Co., which in the '30s turned the image of a lumbering apatosaurus into a smiling icon named Dino who still creates the impression that the big lizards had a crucial role in the creation of oil. "Many people think oil comes from squashed dinosaurs," said Salmon. "But it doesn't. It comes from [squashed] plankton."

The darker side of paleontology is also examined through what was known as the "bone wars" of the mid-19th century. The dispute involved Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope, two highly regarded American paleontologists who competed to be the first to discover, identify and publish names of new dinosaurs. The ego battle resulted in the former friends slandering each other in journals, stealing and destroying each other's fossils.

The exhibit notes that the rush to be first meant sloppy site work, poor documentation of data and haste to publish, issues that are still being sorted out.

Andrew Milner, a paleontologist at the track site who helped create the exhibit, said clashes among paleontologists still occur in the pages of scientific journals, but no longer include the wanton destruction of bones. "Usually it's over issues like plagiarism," he said.

He's betting visitors will be most surprised to learn that some familiar looking animals largely considered dinosaurs by many are really not.

Among the examples are a dimetrodon, a meat-eating beast that has what looks like a sail running down its spine, but lacked characteristics typical of real dinosaurs, such as a skeletal structure.

Plesiosaur, a creature that lived and fed in the water and resembles popular renditions of the legendary Loch Ness Monster "Nessie," is another example.

"They are identified as dinosaurs, but are not," said Milner, who noted both species existed before the appearance of dinosaurs and developed along independent branches of the evolutionary tree, with some possibly even becoming mammals.

He said even mammals such as mammoths and mastodons, which more recently roamed the planet, are often miscast. "Just because they are labeled dinosaurs, people assume they are," he said. "That's not always true."

Steve Stephenson, the director of the southwest Utah chapter of the volunteer group Utah Friends of Paleontology, said the exhibit complements what can already been seen at the track site museum.

"It's good," he said of the exhibit. "It will give people something extra to know who come in to look at the tracks."

The real truth about dinosaurs

P "Dino Right, Dino Wrong" exhibit at Discovery Track Site is open at Johnson Farm.

Where • 2180 E. Riverside Drive, St. George.

When • Exhibit runs to March 1. Museum hours are 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., Monday through Saturday.

Cost • $6, $3 for children 4 to 11, free for kids under 4. Group rates are available.

More info • nature.nps.gov —

Notable names in paleontology

Robert Plot, 1640-1696 • A chemistry professor at the University of Oxford claimed a fossilized bone came from an elephant brought to England by invading Romans in A.D. 72. But it later was determined to have come from a megalosaurus.

George Cuvier, 1769-1832 • French zoologist was the first to recognize that past life forms had become extinct.

Sir Richard Owen, 1804-1892 • English anatomist, biologist and paleontologist who established the British Museum of Natural History and created the taxonomic group Dinosauria or "terrible lizards."

Joseph Leidy, 1823-1891 • Considered the father of modern paleontology, he is credited in 1858 with publishing a paper on the first dinosaur skeleton identified — one from New Jersey. He identified the bones as a duck-billed hadrosaur. He became so frustrated by the "bone wars" of the mid-19th century that he abandoned the field.

Source: Discovery Site museum