This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Dan met the boy he would molest at a swimming pool.

He was 51. His victim just 12.

The boy didn't tell anyone about the groping. Dan asked him not to. And so it went for two years.

Until the boy's mom found out. Until police arrested Dan. Until he pleaded guilty. Until he went to prison for eight years. Until, until, until — it's the sinuous chorus that runs through Dan's mind even today, years later.

Now 68, Dan has a difficult time talking about the sexual abuse he perpetrated. He doesn't expect sympathy — he knows he won't get it. And he doesn't forgive himself — he feels he won't ever deserve it.

So he staggers forward, clinging to the small way he's found to contribute since serving time that offers him a sliver of self-worth. Dan spends his days managing a special affordable-housing unit run like a hotel in downtown Salt Lake City. It houses former felons, sex offenders and homeless individuals, providing clean sheets and a sense of purpose for up to $330 in monthly rent.

Home and work

On the pale pink wall in the lobby of the HomeInn Hotel hangs a small poster: "Don't judge me by my past. I don't live there anymore." It's the philosophy Brent Willis had in mind when he and his wife, Naomi, started the unit in 2010.

Willis doesn't ask prospective residents to complete a background check or mark a box on the application form for criminal history, though most have one.

"We know the direction they're moving, not where they've been," he explains.

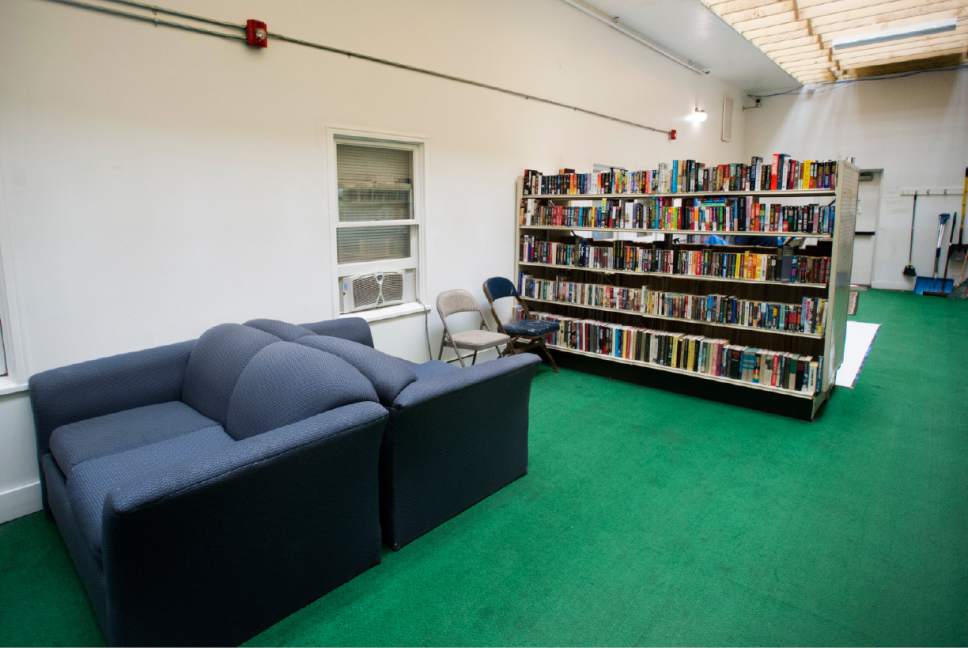

To get and keep a room, the 53 tenants — Willis calls them "guests" — are required only to work or volunteer in some capacity. For about 15 residents, that employment is at the hotel itself. Every janitor, night watchman and plumber who works at the HomeInn also lives there.

In scrubbing the floors, washing the windows and taking out the trash, Willis says, those coming from prison, shelters or the street develop responsibility. They learn commitment and how to maintain a clean home.

For a building first opened in 1911, it's immaculate.

In its early days, the facility housed low-income railway workers near Salt Lake City's two depots. Today, the old Rio Grande Hotel electric sign still hangs over the facade at 428 W. 300 South, reminiscent of that past.

A chance

Dan hesitated at the brass numbers fixed to the hotel door — 217 — before pressing it open and walking inside.

"It's bigger than my cell I had," he explains.

The room, hardly larger than a walk-in closet and crowded with a twin-size bed and sink, is the home he's created since leaving Utah State Prison. Eleven lighthouse figurines sit on top of the window, reminding him of his childhood in Rhode Island. A signed poster of Red Sox legend Ted Williams hangs on the wall. And a wooden Geppetto doll he picked up at a thrift store smiles from its perch on a shelf.

"I got him for a buck," Dan says with pride and a thick East Coast accent. "One buck."

When Dan got out of prison, most everything he'd owned was gone except for a few Christmas ornaments from his mom.

Though he clings to the few reminders of his past, Dan doesn't like to tell people his last name. He worries they might recognize him from his years as a swim coach and know how he came to lose that job. Also skittish about anything that could damage his final parole hearing in two months, he asked to be identified only by his first name.

Dan, who looks like a younger, thinner version of Anthony Hopkins, left prison with just two things: the first, a handful of memorized statistics about sex-offender recidivism that he rattles off upon introduction.

"Some 96 percent don't ever go back [to prison]."

He's not far off. The federal rate for offenders returning to prison for a repeat sex crime hovers around 3.5 percent to 4 percent. It's slightly lower, 3.3 percent, for those who commit sex abuse of a child. Dan doesn't mention that number, but it's easy to see that he trusts in the statistics. He believes the data and the hotel will save him from hurting another kid.

"There's an opportunity to change your life here," he says.

That commitment requires the second thing he left prison with — a devotion to routines.

Rhythm and meaning

As the facility manager, Dan is charged with overseeing the hotel's custodial staff. He makes the rounds every day to check their work, walking around the building with a white rag in search of dust or dirt. He rarely finds any. That makes him proud.

When he's not working, Dan spends his time walking outside: 25 miles every week — 12 on Sundays — to stay fit.

And once a month, Dan walks down the steep set of wooden stairs to the basement of the HomeInn to attend a "self-reliance course," which is required for all residents. They learn life skills, like budgeting, and ways to mend.

These walks are the rhythm that make up Dan's life. They keep him busy. They keep him determined. They keep him distracted.

Finding meaningful routines and employment is the hotel's model for all guests. And it works.

Some 85 percent of residents move on to better housing, says Brent Willis, the owner.

Willis began leasing and repurposing the downtown hotel from the city about seven years ago after working in the real estate business that he says was "never fulfilling." He runs a similar, smaller facility in Kearns.

For former inmates, particularly felons and sex offenders, finding landlords who don't discriminate can be like a game of Minesweeper without the clues. About half the residents of the HomeInn Hotel fall in that category.

The guest manager spent six months in prison on a felony charge for yelling at a passenger on an airplane. The downstairs janitor pleaded guilty to six counts of sodomy and rape of a child. The admission specialist served 12 years for attempted aggravated abuse.

"The people that we have in here can't find anywhere else to live," says Leesa Garner, the hotel's financial controller.

Under the federal Fair Housing Act, there are seven protected classes for tenants, including race, sex and disability. Having a criminal record is not one of them.

Private landlords can legally choose not to rent to a person based on his or her past convictions — which some 20 percent to 30 percent of the population have.

Until recent legislation passed, Utah property owners received breaks on their licensing fees for refusing to house individuals with criminal backgrounds. Though these "good landlord programs" have since been stripped of that incentive, Salt Lake City, West Valley City and Ogden — where most former inmates in the state relocate — were exempted.

This presents a challenge for reducing recidivism.

"It's very clear that having stable housing is a critical component of success for anybody that's leaving prison and entering into society again," says Ron Gordon, executive director of Utah's Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice.

Without a place to stay, former inmates may break the terms of their probation, attempt to speak to their victims in a search of shelter or wind up homeless.

The HomeInn is rare, then, in its targeted effort — not as a halfway house or a treatment center — to take in people with criminal records, offering rooms and second chances when many apartment complexes in the state (and country) don't.

"If there were another building we could get," Garner says, "we could fill it tomorrow."

About four of the 53 tenants transition to better housing each month. Still, 90 names often are scribbled on the waitlist.

Homeless in Salt Lake

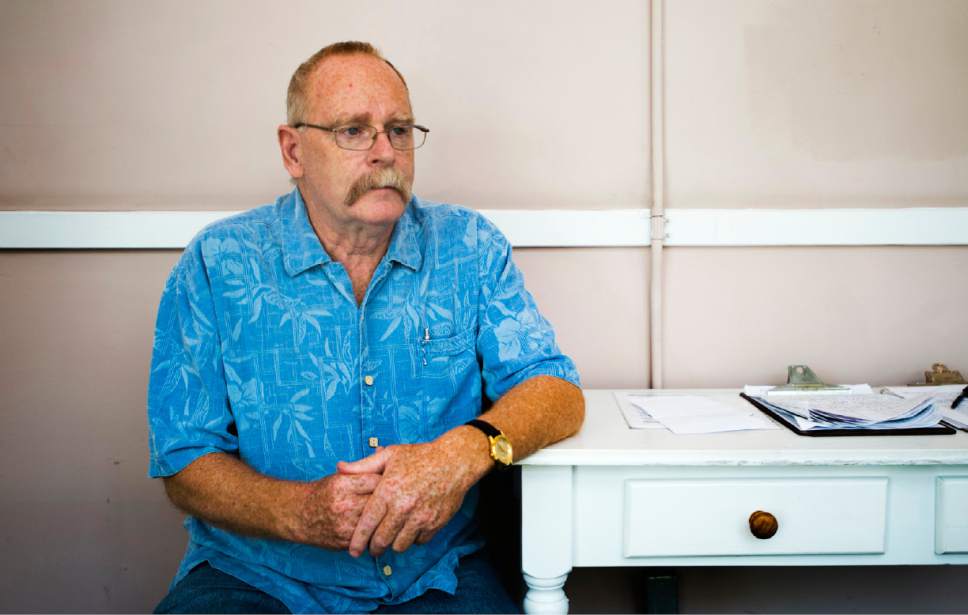

Jim Head sits at a white wooden desk no more than 3 feet wide, reading out a phone number "8, 0, 1 …"

The other man in the room, who goes by Ellis, slowly dials. "I can't see without my glasses on," he says.

After three weeks of waiting, Ellis is about to get a room at the hotel. He's been living out of his car for much longer than that because he can't afford any place else. That dilemma is evident in the blocks surrounding the HomeInn.

A room with a single bed at the hotel across the street, Homewood Suites, starts at about $169 a night. A studio at one of the handful of apartment buildings in the area ranges from $800 to $1,000 per month.

For those working a minimum-wage job or living off of disability checks, even the HomeInn's rate bottom of $225 a month for a double room can be unmanageable. But it's at least within reach.

Head, who's lived at the hotel since he left prison in 2013 after serving time for a three felony sex offenses, helps people in "various situations that came upon them" find housing with the HomeInn. As the admission specialist, he sits in his office, watching homeless individuals stride past the front windows on their way to the shelter around the block, and talks with those who wander inside.

The hotel doesn't use a simple first-come, first-served rule to fill its rooms. Instead, applicants have to continually check in with Head to show they're willing and motivated and committed.

When somebody is ready to change, Head says, "you can recognize it."

He sees about 30 people a week, moving promising candidates higher up on his clipboard and filling rooms the same day they're vacated.

"It gives me a purpose," he says. When asked about their jobs at the hotel, many other residents have the same answer.

As leaders develop plans — including the construction of two new shelters in Salt Lake City and one in South Salt Lake — to address the swelling homeless population, it's possible the efforts will include purchasing run-down motels along State Street and North Temple to convert into temporary, transitional housing.

The HomeInn Hotel is "a general model of how that could work," says Mike Reberg, Salt Lake City's director of community and neighborhoods. Despite recent pushes to develop more affordable-housing complexes, Reberg says, there is a shortage of 7,500 units for those on the lowest end of the low-income scale.

The HomeInn caters to that population, but it started on a whim. The city's Redevelopment Agency bought the property as a temporary replacement for another historic hotel it demolished and planned to rebuild. That was never completed. So the hotel has continued its lease.

A reminder

Dan points down the hallway at the rooms of each person he lived with in prison.

"Now we're neighbors again," he says with a grin.

Many of the hotel's formerly incarcerated guests have formed support groups to talk about their crimes when guilt or shame resurfaces. Gordon, with Utah's criminal-justice commission, says it's a productive way for former inmates to "police one another." The conversation often comes back to family and relationships.

Dan talks about his daughter, how she won't speak to him, not since he pleaded guilty anyway. It only makes him more remorseful for what he did.

The 12-year-old boy Dan abused is identified in court documents as R.B. Those initials appear every time Dan did something inappropriate: He would "regularly kiss R.B. on the mouth." He "pulled down R.B.'s underwear." He "touched R.B."

Dan's daughter had tried to defend her father but ultimately found that she could not.

Dan includes her name in a list of his regrets and keeps a picture of her on his bulletin board. It's surrounded by scraps of paper — a quote from Albert Einstein, a reminder from his boss, a Christmas card.

There's one note taped off to the side just outside the brown cork frame. In a mix of capital and lowercase letters it says: "What have I learned?"

"I read it every day, several times a day," Dan says. "Sometimes I start to forget what I have gone through and what I have caused other people, the pain."