This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Art imitates life, the saying goes. In rare cases, it also imitates politics.

Salt Lake Acting Company's 2011 musical satire, "Saturday's Voyeur," turned inward — and onto the stage of the most contentious topic to hit Utah theater in years: Salt Lake City Mayor Ralph Becker's proposed $100 million, 2,500-seat, "Broadway-style" theater.

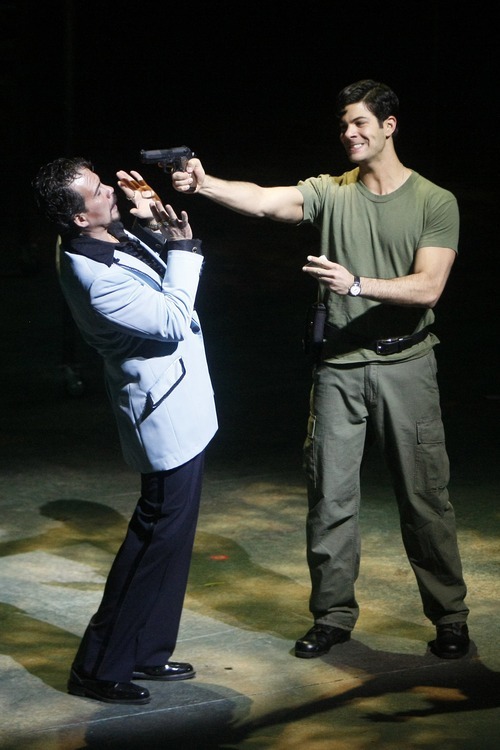

The shot comes when Becker, wearing a bicycle helmet and played "smugly calm and slim" by Alexis Baigue, crunches numbers with the play's calculator-wielding "Bimbo."

"Do you really think it's feasible for people to give 10 percent of their income to your pet project?" she asks.

"Hey, the [LDS] Church has been getting away with it for more than 150 years," the mayor answers.

Those lines draw snorts galore. Behind the curtain, however, Utah's theater community isn't laughing. Nor are some taxpaying skeptics who wonder why Becker seems bent on tossing that kind of money at such a large, even lavish, project.

"It feels as though this is an attempt by well-meaning leaders to keep up with neighboring cities such as Phoenix or Denver," says Royce Van Tassell, vice president of the Utah Taxpayers Association, who notes the price could swell by an additional $10 million in interest between the theater's planned 2013 construction and 2015, when the city's funding mechanisms would become available.

The proposal brings to the fore myriad questions, including whether other venues would survive the introduction of a Utah Performing Arts Center (UPAC) on Main Street, whether audiences here would embrace a wider array of traveling Broadway productions and whether such shows would drive up interest in the arts as a whole.

Those at the helm of established arts organizations worry that city officials have overplayed the power of the arts as an economic tool, especially during a time when funds for all arts organizations come at a premium.

"This may be inevitable and is something that should be considered," says Melia Tourangeau, CEO of Utah Symphony | Utah Opera. "But regardless of what's said about it being a self-sustaining venue, I'm highly skeptical of that being the case."

—

"What is the need?" • It's not the first time Becker has drawn controversy over a proposal to redraw downtown's map. After public outcry, the mayor opted to place a planned $125 million Public Safety Building just east of his first choice, Library Square.

By contrast, he seems resolved to see a Broadway-style playhouse at or near 135 S. Main. If all goes as planned, the building would bear the imprint of Moshe Safdie, the same architect who designed downtown's showcase library. Part of his motivation, Becker says, is driven by the desire to link a long-dormant part of Main with the LDS Church's $2 billion City Creek Center to the north and Gallivan Center and office towers to the south.

"We do not have a catalyst for blocks in between," Becker says. "This will pull parts of the city together and add to our proud tradition of supporting the arts."

The effort is also something of a Becker family affair — with the 2008 enlistment of brother Bill Becker, a Tony-award-winning producer, to help guide the project.

"The last thing I want to see — and I've told this to my brother — is to go into a project that everyone's going to call a white elephant five years later," Bill Becker says. "That's the last kind of legacy I want."

Whether the theater would be a boon or a boondoggle is impossible to predict. Even taking into account population growth and market research, there's no sure-fire way to measure how many seats in existing venues — Kingsbury Hall, Capitol Theatre and Pioneer Theatre Company chief among them — would be left full or empty if UPAC joined the scene.

"None of the arguments for this theater I've heard address the central question. That is, 'Really, what is the need for this?' " says Chris Lino, PTC's managing director. "First of all, every major tour that's been put out on the road has come here eventually. Second, a theater of that size is — with minor exceptions — only usable by for-profit presenters."

—

New theater, old story • Few items on Salt Lake City's wish list have had such a long life.

"It was talked about so often, for so long and in so many guises at Salt Lake County that [County Councilman] Randy Horiuchi used to call it 'The Big A— Theater,' " says Joe Hatch, a former council colleague.

The city's 1962 Second Century Plan listed a number of projects — including the LDS Church's Main Street Plaza — worthy of future implementation. Almost 50 years later, a UPAC-type venue remains a holdout. The Salt Lake Chamber reminded civic leaders of the theater's promise with its 2007 Downtown Rising plan. Out of eight "signature projects" the plan outlined, UPAC was identified as key to downtown vitality.

"We look at a lot of projects with cynicism," says Natalie Gochnour, the chamber's executive vice president. "We've gotten to the point where the vast majority of business leaders support this project."

John Ballard, president of Utah-based presenter MagicSpace Entertainment, has also been a proponent of a larger theater space. Proof the venue would succeed, he says, is manifest every time someone asks him when the Tony-winning "Book of Mormon" musical will hit Salt Lake City.

Ballard also points to Broadway's smash season of more than $1 billion in box-office sales, with 12.5 million people attending plays such as "War Horse," "Jerusalem" and musicals such as "The Scottsboro Boys." And with the renegade humor behind the thriving "Book of Mormon," some say the way has been paved for a new generation of musicals appealing to younger theatergoers.

"Two years ago, our subscription rate went up 30 percent, even during a recession," Ballard says. "On average, every season I miss a show I'd like to book but cannot because there's no venue available."

Hatch, who helped oversee Salt Lake County's Cultural Facilities Master Plan, says countywide polling shows solid support for a Broadway-style venue. Moreover, he believes it would help bridge the cultural and political divide between Salt Lake City and its southern neighbors.

"We've been looking for common ground forever between the gentile, liberal community of Salt Lake City and the devout, Republican Mormons of south Salt Lake Valley, and we've found it," Hatch says. "It's musical comedy."

—

If we build it, will they come — sooner? • But if support among civic leaders has grown, selling the public is another matter. Two studies draw seemingly contradictory conclusions.

A $200,000 county study by AMS Planning & Research reported in November 2008 that the valley's stage-entertainment needs were already "adequately met."

But a $741,000 city study released this year by Swisher Garfield Traub predicted a new theater would "pave the way for the planned cultural core district as a regional attraction and economic development engine for Salt Lake City."

Conflating the two studies would be wrong, says Steven Wolff, founding principal of Connecticut-based AMS Planning & Research. (Wolff's firm acted as arts marketing consultant for the later study.) The county study was not commissioned to evaluate the need for a Broadway-type theater in Salt Lake City proper, Wolff says. Instead, it sought to evaluate countywide cultural needs.

UPAC backers point out that touring Broadway shows have needs, too, and those needs align with those of future Utah audiences. According to their accounts of interactions with national promoters, existing county-run venues such as Abravanel Hall, the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center and Capitol Theatre no longer suffice.

Abravanel is the domain of the Utah Symphony | Utah Opera, a premier acoustic venue that also sees occasional comedy and concert productions. Rose Wagner is designed for smaller-scale theater and dance productions, currently filled by Plan-B Theatre Company and Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company.

The main problem of the third facility, Capitol Theatre, is that its size hasn't kept pace with market growth, say UPAC supporters. For touring Broadway troupes, including the spring showing of perennial Utah favorite "Les Misérables," it has served as venue of choice.

A more fitting description might be venue of default. Melinda Cavallaro, the county's Center for the Arts events director who works with promoters nationwide to book shows, estimates the county loses six to 10 touring shows a year because existing venues fail to provide the seats necessary to cover production costs.

"They still call," Cavallaro says. "But they know it's a shot in the dark."

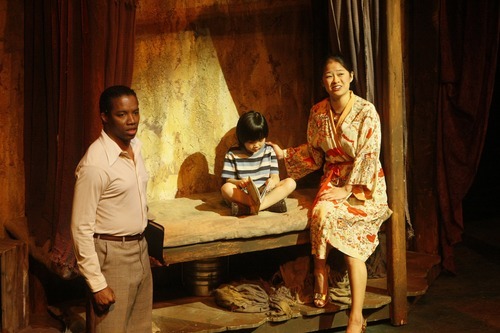

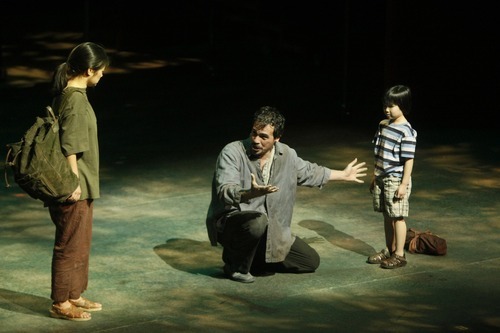

Touring productions also complain of Capitol's capacity — or the lack thereof — for loading and unloading sets. Its cramped quarters result in smaller-scale productions of less grandeur. The touring show of "Miss Saigon," for example, lacked the helicopter set piece that graced the original.

But it's not the performance alone that suffers, Ballard says.

"There's bigger economic benefit to having touring shows come here sooner than later," he says. "As shows get older, in terms of touring runs, they leave more and more trucks behind. By that time, too, people will have traveled to other markets to see the show."

At Pioneer Theatre, Lino challenges the notion that the benefits of a first- or secon-run touring show outweigh UPAC's price tag. It's clear, he says, that demographics and market size, not venue size, drive decisions to stage a show in one city over another.

Lino cites the national tour of Andrew Lloyd Webber's "Phantom of the Opera." It played at San Francisco's Curran Theatre, which holds 1,667 seats, four years before coming to Salt Lake City's Capitol Theatre, with 1,940 seats.

"We've watched the evolution of arguments in favor of this venue change several times over the years," Lino says. "First, they argued that touring productions don't come here because of our small venues. But that's clearly not true because 'Wicked' and 'Lion King' have played here. Then they changed their argument to one of first runs being superior to a third, fourth or fifth tour."

—

Venues and vital stats • Greg Geilmann, executive director of Kingsbury Hall, also scoffs at pro-UPAC arguments.

In a frank March 22 memo from the county's Center for the Arts to D.J. Baxter, executive director of Salt Lake City's Redevelopment Agency, the county predicted "significant reduction" to the future revenues of Capitol Theatre and Abravanel Hall if UPAC is built. Total revenue losses would run about $1 million the first year, but could be reduced over time to about $600,000 if the Center for the Arts developed "new strategies" to book events at Abravanel and Capitol as certain shows migrated toward the new theater.

Unmentioned is Kingsbury. Owned and operated by the University of Utah, the venue schedules its musicals in ways that don't interfere with similar productions at nearby PTC.

"They still have their head in the sand," Geilmann says. "The county has said it will affect revenue at Capitol and Abravanel to the tune of at least $600,000. We've done our own analysis and feel strongly that Kingsbury Hall could lose as much as $400,000 annually from competing rentals and lost ticket sales. Put those two together and you've got a $1 million hole."

Even UPAC would need years to reach full operating capacity. Touring Broadway productions are projected to fill up 10 weeks of scheduling, plus one three-week span of a "blockbuster" every other year for a total of 135 "venue days." The remaining dates, according to the city's study, would be filled by holiday productions, nonprofit events, commercial promoters, opera, ballet and symphony performances.

Granted, not all these shows would make "Book of Mormon" musical-type money. But UPAC proponents say decision-makers should never underestimate the length, or strength, of Broadway's coattails.

"When people look at a season-ticket package, they look at whether or not they get to see a blockbuster the first time around," Bill Becker says. "You really need that spark. Right now, we don't have a theater that can generate that."

Halsey North concurs. His New York-based company, The North Group Inc., has developed arts-center and theater-restoration projects for almost 40 years. Big Broadway shows are "transformative," North says, so much so that they can subsidize a venue's money-losing productions and even spur greater public interest in all the arts.

"It's really a spurious argument to say, 'We can't fill the seats we have now,' " North says. "It's all a matter of interest and having the interest of your audience. Small theaters always struggle for that spark. But if you get people in the habit of going downtown to see the big shows, that's one of the best ways to get them interested in everything else in the local theater world."

—

How family-friendly is Broadway? • Making Salt Lake City more theater-centric would come at a cost — one paid, ultimately, by ticket buyers.

The "Saturday's Voyeur" scenario of Utah families paying "10 percent" to finance UPAC serves the play's satire. Closer to reality is a harder question: Given Utah's larger-than-average families and lower-than-average incomes, how many would pry open their wallets for shows in the starting range of $100 and up?

Lino and Geilmann doubt it, citing touring Broadway productions in Salt Lake City that left plenty of seats cold.

"If you look at the attendance of lesser-known or regular productions that come in, they're not operating at capacity," Geilmann says. "Sometimes they're in the 70 percent range."

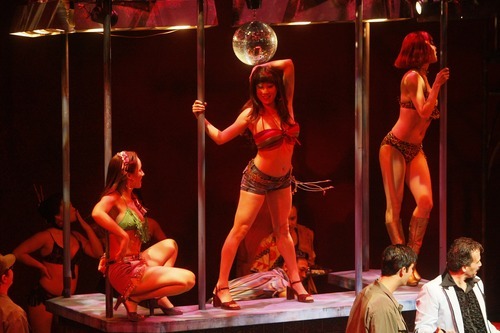

Empty seats aplenty greeted "Spring Awakening" when MagicSpace brought the highly touted musical to Kingsbury. Not even the show's sultry soundtrack by indie rocker Duncan Sheik prevented some from leaving at intermission.

That a show about adolescents in the throes of sexual maturation failed to enchant a Utah audience pivots toward another question: Once the crowds for "Les Misérables," "Lion King" and "Wicked" in the larger, roomier confines of UPAC have dispersed, would they return for riskier productions that draw East Coast raves?

Patrons would at least get that chance. City Hall insists the LDS Church, which is selling the theater parcel to the city for an as-yet unknown amount, has agreed not to interfere with any content control. What's more, the city would never allow it.

"Absolutely not," Becker says.

That means Broadway's bawdy "Book of Mormon" could be offending Utah audiences as soon as presenters take it on the road. In March, co-creator Trey Parker wrote in an online chat that his profane play "will play there in some form at some point."

"We've been advised by experts in the industry," says Becker's senior adviser Helen Langan, "that 'The Book of Mormon' would be a sellout in the Salt Lake City market."

"Saturday's Voyeur" has not brought Salt Lake City's "gentile, liberal" community and the suburbs' "devout, Republican Mormons" into one theater. But no one can deny the near cultlike following it has developed over more than two decades — even if it requires a rotating cast of characters that, this year at least, lobs arrows toward the mayor and his sibling.

"My brother Bill says the appetite for overcooked French musical melodramas in Utah is still huge," says Baigue, playing the mayor's alleged naiveté to its dramatic hilt.

"If SLAC wants to put me in a script, that's fine," Bill Becker says. "I've got thicker skin than that, but there's probably a point at which you could prick me."

Until UPAC is built and proves its success, the mayor's brother may have to endure many more pricks.

bfulton@sltrib.comTwitter: @Artsalt

Tribune reporter Derek P. Jensen contributed to this story. —

Tale of two venues, Durham, N.C., and Salt Lake City

A key part of downtown sagged. You wouldn't think its demographics, largely conservative with incomes nowhere near East or West Coast levels, would support touring Broadway productions. And yet, when the Durham Performing Arts Center cut its opening ribbon in 2008, the 2,712-seat venue went on to prove the naysayers wrong.

So is the idea of Salt Lake City embracing a similar project really so wild-eyed?

If the Durham theater is any indication, the answer could be a qualified "not at all."

"A lot of people were skeptical," says Aaron Greenwald, promoter for Duke Performances at nearby Duke University. "Now I think even those who run the venue would never have sanely projected the success they've had."

Greenwald says promoters in North Carolina's tri-city area of Raleigh, Durham and Chapel Hill were also surprised at how well people responded to the steep ticket prices, which climbed as high as $120.

"We learned the community would rather be in a 2,500-plus seat venue and pay $80 to $100," he says, "than be in a hockey arena and pay less."

Ted Conner, vice president of economic development for the Durham Chamber of Commerce, says maintaining a private operator and promoter for the venue was crucial to its success. Durham owns the $48 million center, contracting with New York City's for-profit Nederlander Producing Company of America to book shows. The city shares in the profits, Conner says, and received a $400,000 check after the venue's first year.

Not everyone ended up a winner. Raleigh's Memorial Hall, Greenwald says, had to "seriously retrench" its own series of traveling Broadway productions.

"They've eaten into everyone's ticket sales to some extent, some more than others," he says. "But in some ways it's foolish to complain about, because no one's stealing anything from anyone. They [DPAC officials] are just doing their job of selling the best shows possible in the most seats possible at the best price possible."

Ben Fulton