This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The area is flat, white and desolate, a giant expanse of salt crystals where not even a blade of grass grows.

For Ab Jenkins — Utah native, race-car driver, safety advocate, and for a time during World War II, the mayor of Salt Lake City — it was a second home. The Bonneville Salt Flats was a place he made famous, as well as a place that made him famous.

Now, Jenkins and his triumphs on the salt flats are being celebrated in a documentary, "Boys of Bonneville," which has been screened at film festivals and now will receive a two-week run at the Megaplex Theatres in Salt Lake City, Sandy, South Jordan and Ogden, starting Friday, Aug. 26.

A century after Jenkins first rode his motorcycle on the salt flats, and more than 60 years after he set land-speed and endurance records — some of which still stand — the wide desert west of Salt Lake City "is the place to do land-speed," said Curt Wallin, the film's director.

Last week's annual Speed Week, which just concluded, drew some 15,000 racing enthusiasts — some of whom were treated to an advance screening of the movie at Wendover's Peppermill Concert Hall.

"They're just so glad somebody put all this together, all this stuff that's in everybody's heads," said John Greene, editor and co-producer of the film.

—

'The Mormon Meteor' • Ab Jenkins, born in Spanish Fork and raised in Salt Lake City, discovered the Bonneville Salt Flats in 1910, riding his motorcycle to Reno to see Jack Johnson fight Jim Jeffries in the "Fight of the Century."

In 1925, when the first highway was built through the west Utah desert, Jenkins raced the train in an automobile — and won by five minutes.

Starting in 1932, Jenkins set out to make Bonneville the place to race. He started with a 12-cylinder Pierce-Arrow that he ran for 24 hours, stopping only to refuel but never leaving the driver's seat. He set an average speed of 112.916 mph, but the AAA refused to sanction the record. In 1933, with AAA's blessing, Jenkins did it again. Then he lured British racers like Sir Malcolm Campbell, E.T. Eyston and John Cobb to Bonneville.

"In Ab's day, when he brought the British in 1935, they had run out of room," Greene said. "Cars were better, cars were faster, and there was absolutely no place on Earth that they could go as fast. They had to build new tracks, but asphalt hadn't been invented, really, so that's not going to work. They had tried on Daytona, but people were getting killed, because as good as the surface was, they still had to go under piers and along hotel fronts. So Ab's out here going, 'Guys, I've got the answer.' … Not only was it just bigger, it was a lot safer, because you can't dig in, you can't flip, you can't run into anything."

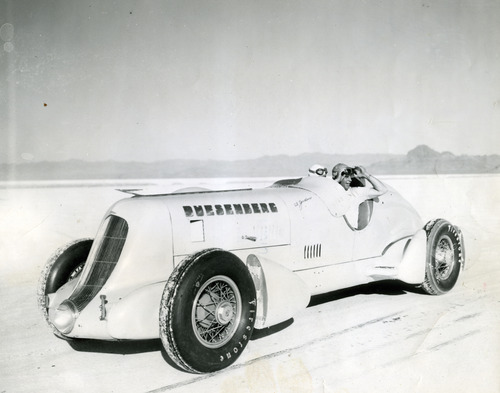

The Brits broke Jenkins' speed records, and Jenkins turned around and broke them again in 1935 in his "Duesenberg Special," aka the Mormon Meteor II, a racing car with a 1924 Curtis airplane engine.

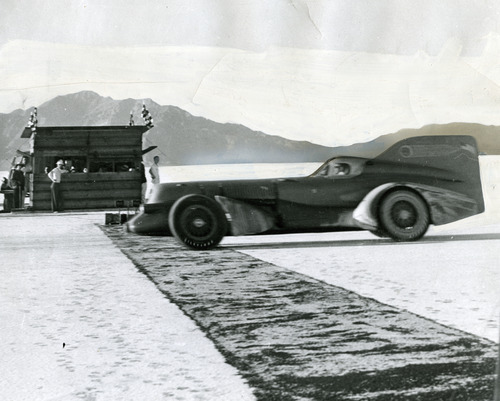

In 1938, Jenkins and Augie Duesenberg, the legendary automotive engineer, worked together to create a new racer, the Mormon Meteor III. For the next two years, Jenkins ran the Mormon Meteor III at Bonneville regularly. In 1940, at age 57, he set another 24-hour speed record, an average of 161.180 mph — a record that held up for 50 years.

When he set the 1940 record, Jenkins was holding down another job: Salt Lake City mayor. He was elected in 1939, without spending a dime on campaigning or giving a single speech.

—

'A pile of film' • Making a movie about the Mormon Meteor III wasn't supposed to be such a big deal.

John Price, the Utah philanthropist and former ambassador to Mauritius and the Seychelles, asked Wallin to make a short movie — between 10 and 20 minutes — about the car. The film was planned to play on a loop at the Price Museum of Speed, scheduled to open in 2012 in downtown Salt Lake City. Price had purchased the Mormon Meteor III from Marv Jenkins for the museum.

"I went down [to St. George] to meet with Marv and just found a pile of film," Wallin said. The footage included hours chronicling Ab Jenkins' racing career, including the 1933 Pierce-Arrow run and color footage of the 1940 drive in the Meteor. Still images of the 1932 Pierce-Arrow run showed there were film cameras shooting the event — and when Wallin requested footage in online chat forums, a DVD arrived in the mail.

Watching the film, Wallin and Greene marveled at the dangerous camerawork involved. Some footage was shot hanging out of a biplane flying parallel to Jenkins' car, while other scenes were taken by a camera strapped to the car itself. "How they got the camera under the car to look at the driveshaft and the tires, I have no idea," Greene said.

The film features interviews with plenty of racing lovers, from British Col. Andy Green (the current world land-speed record holder) to comedian and car enthusiast Jay Leno. And, perhaps most important, Wallin (who is also the film's cinematographer) captured the painstaking restoration of the Mormon Meteor III, overseen by Ab Jenkins' son Marv — who worked alongside his dad throughout his record-setting days and arguably logged more hours in the Meteor than his old man.

The filmmakers had so much story that the film became unwieldy, and a rough-cut ran to 3 1/2 hours. Wallin and Greene went to editor-writer Michael Chandler and screenwriter Jennifer Jordan (who became a co-producer) to trim the footage into a manageable length.

Chandler and the filmmaking team combed through newspaper interviews with Jenkins — as well as a ghost-written memoir and a 1937 article in The Saturday Evening Post — to create a first-person narration in Jenkins' words.

"Ab did not leave a diary, and he wrote very few letters," Jordan said. "Here's this man who lived on the road. He must have had quite a phone bill."

Thanks to connections of the Salt Lake City Film Center's Geralyn White Dreyfous (who, along with Price, is the film's executive producer), Wallin landed actor and race-car driver Patrick Dempsey to provide the voiceover of Jenkins' words.

Wallin sent Dempsey a cut of the film, and Dempsey called back late one night gushing about an animated scene illustrating Jenkins' night-driving hallucinations. "He said, 'I've been through it, when I've done the 24 Hours at LeMans,' " Wallin said. "A few weeks later, Jennifer and I were down there [in Los Angeles] working with him. He was great."

—

Restoring the 'Meteor' • After Ab Jenkins stopped racing, he donated the Mormon Meteor III to the state of Utah. For decades, the car was on display in the Utah Capitol.

The state wasn't always the best caretaker.

"It wasn't properly protected, and kids were scratching their names into the tires and putting paper and gum into the exhaust pipes, stealing the gauges out of it," Wallin said. In the 1970s, the state started taking the Meteor out for the Days of '47 parade, and sometime in the early '70s let it sit outside for three months exposed to the elements.

"All those years go by, people start forgetting what the importance of it was," Wallin said. "There was no intentional malice."

In 1991, Marv Jenkins got so fed up with the state that he backed a flatbed truck up to the Capitol and took the car to St. George. Eventually, master mechanic Roger Brasier, with Marv Jenkins as a consultant, oversaw an extensive engine restoration.

The Mormon Meteor III is now in as good shape as it was when Jenkins first drove it. It will be part of an exhibit, "Speed: The Art of the Performance Automobile," opening next June at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts at the University of Utah. After that, it will take up permanent residence at the Price Museum of Speed.

Jordan believes the movie helps further one of Price's goals: to make the world recognize the beauty and importance of the Bonneville Salt Flats.

"He wants to see the Bonneville Salt Flats right next to the billboard of Canyonlands, right next to the billboard of Zion Park," Jordan said. "He, and the world, sees Bonneville as this amazing pristine and gorgeous place, and a resource for people from all over the world, that is forgotten locally in a really ironic way."

She added: "The racing world knows about Bonneville. It's going to be interesting to see how the world reacts to this gem."

Twitter: @moviecricket

facebook.com/themoviecricket; facebook.com/tribremix —

A timeline: Ab Jenkins, the Meteor and the Bonneville Salt Flats

1845 • John C. Fremont makes the first recorded crossing of the west Utah desert.

1883 • David Abbott "Ab" Jenkins is born on Jan. 25 in Spanish Fork.

1910 • Riding his motorcycle, Jenkins becomes the first person to run a motorized vehicle on the Bonneville Salt Flats.

1914 • Daredevil Teddy Tezlaff drives a Blitzen Benz 141.73 mph to set the first unofficial land-speed record on the Bonneville Salt Flats.

1925 • To inaugurate a new highway through the salt flats, Jenkins races a train in an auto across the desert — and wins by five minutes.

1926 • Jenkins drives from New York to San Francisco in 86 hours, 20 minutes.

1932 • Jenkins drives a 12-cylinder Pierce-Arrow auto for 24 hours (without ever leaving the driver's seat) on the salt flats. AAA refuses to sanction the record.

1933 • Jenkins races another Pierce-Arrow to another record on the salt flats — this time with AAA approval. The same year, top British racers Sir Malcolm Campbell, Capt. E.T. Eyston and John Cobb visit the salt flats for the first time, setting records and launching the site's global reputation.

1935 • Jenkins drives the Mormon Meteor II, also known as the "Duesenberg Special," with a 12-cylinder Curtis airplane engine, setting a 24-hour average record of 135 mph.

1938 • Working with the legendary auto engineer Augie Duesenberg, Jenkins develops the Mormon Meteor III, a racer specially designed for the salt flats.

1939 • Jenkins takes the Mormon Meteor III to the Bonneville Salt Flats, again setting land-speed records, and accidentally catches himself on fire. The same year, Jenkins is cajoled into running for mayor of Salt Lake City and wins the election without campaigning.

1940 • While mayor, Jenkins sets the 24-hour speed record, averaging 161.180 mph — a record that would stand for 50 years.

1944 • Jenkins completes his term as mayor.

1950 • Jenkins takes the Mormon Meteor III for a last long run, setting 26 American and world records. Soon after, he donates the Meteor to the state of Utah, which displays the car at the state Capitol for many years.

1956 • Jenkins dies on Aug. 9 during a trip to Milwaukee.

1970 • Gary Gabolich's rocket car, "Blue Flame," attains a speed of 622.4 mph on the salt flats.

1985 • The Bonneville Salt Flats is designated an Area of Critical Environmental concern by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

1991 • The Jenkins family, led by Ab's son Marv, reclaims the Mormon Meteor III from the state of Utah for a much-needed restoration.

2005 • "The World's Fastest Indian," a movie about New Zealand racer Burt Munro (played by Anthony Hopkins) and his efforts to race his modified motorcycle in the late '50s and early '60s, is filmed, in part, on the Bonneville Salt Flats.

Sources • "Boys of Bonneville," Barracuda magazine; Bureau of Land Management; Utah History Encyclopedia —

'Boys of Bonneville'

P The documentary "Boys of Bonneville" will have a two-week run at the Megaplex Theatres — the Megaplex 12 at The Gateway, Salt Lake City; the Megaplex 17 at Jordan Commons, Sandy; The Megaplex 20 at The District, South Jordan; and the Megaplex 14 at The Junction, Ogden —from Aug. 26 to Sept. 8. It's also available on DVD at http://www.boysofbonneville.com.