This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

There is no forgetting the fall.

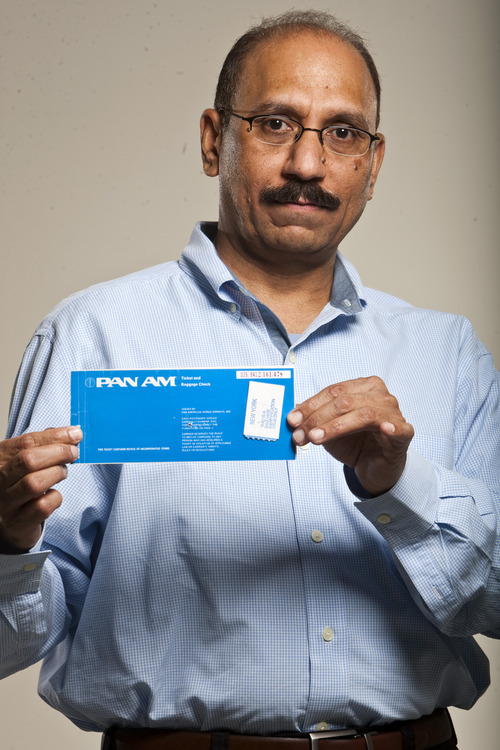

It was a bone-chilling, two-story drop from the wing of a grounded Boeing 747. But Javaid Majid, now of Millcreek, didn't hesitate a second before jumping.

It was the only escape from the gunfire and grenade blasts that marked the violent end of the Pan Am 73 hijacking, in which four terrorists with Libyan ties opened fire on a crowded airline cabin full of hostages after a 16-hour siege that left 20 dead.

"What they did to us," Majid began, his voice wavering. "You can never forget those moments — every second of those 16 hours. I have tried to forget for 25 years."

As Majid approaches the 25th anniversary of that hijacking — on Sept. 5 — his sentiments are bittersweet.

On the one hand: The regime led by Libyan strongman Moammar Gadhafi, long believed to be responsible for the hijacking, has crumbled. Rebels have stormed the capital and effectively deposed the 42-year dictator. Gadhafi's whereabouts remain unknown, and U.S. President Barack Obama has declared his rule over.

"That will be such a closure to me," Majid said, "to have the terrorists get out of this country and bring peace to these people."

On the other: Majid has fought unsuccessfully for two years for a portion of the settlement between the U.S. and Libyan governments for $1.5 billion in outstanding terror-related claims — some of which was set aside for Pan Am 73 victims.

Despite a letter to Obama, pleas for help from Utah's congressional delegation and a formal claim through the U.S. Department of Justice's Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, Majid hasn't seen a dollar of that settlement. That money, the commission said, is reserved for passengers who were U.S. citizens at the time of the hijacking.

Majid said he isn't interested in the money — he talks about donating it if he ever receives a check — but he is interested in justice.

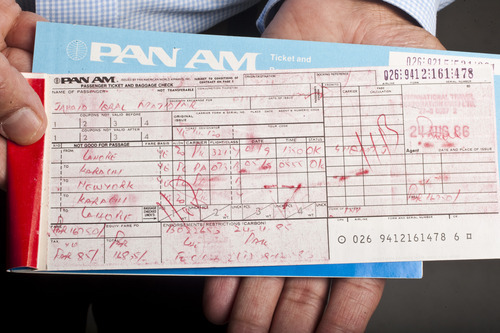

The hijacking happened early on Sept. 5, 1986. At the time, Majid was a young Pakistani with an airline ticket and dreams of studying in New York. Before takeoff in Karachi, Pakistan, four hijackers dressed as security officers boarded the plane with automatic weapons and explosives.

The pilots escaped, leaving the plane and its 360 passengers grounded during a daylong standoff punctuated by the execution of an American.

The hijacking reached a grisly end around 9 p.m. when the airplane's power went out. The attackers unleashed an indiscriminate barrage of bullets and grenades into the cabin, forcing passengers to flee through a side door onto the wing. There, they dropped 36 feet onto the tarmac below.

Although Majid escaped the jet, he hasn't escaped the memories. They were so painful after the attack that he immigrated to America — and ultimately to Utah — to distance himself from them. His father begged him not to go, but Majid said he needed to "break free."

"I wanted to move on," he said. "I didn't want to think about it. I didn't want to connect with anything. Utah was perfect for that."

In 1994, eight years after the hijacking, Majid became a U.S. citizen. He now works as an associate fiscal administrator for Salt Lake County.

Majid continues to mark the anniversary of the hijacking in silence. He seeks solace in the mountains. He takes walks near his Millcreek home.

Even now, he speaks reluctantly about the events that transpired inside the airplane. At times, his eyes grow wet. The images are still too vivid:

Flight attendants hiding American passports as terrorists take control of the plane. Hijackers uttering Muslim prayers, the same ones Majid prayed as a child, before turning their rifles on men, women and children. Passengers scrambling through seats to get to an exit door. Him running across the tarmac on a broken foot, without shoes, after an excruciating drop from the wing. A little girl in his arms as he lifted her, despite his own desperation, over a wall separating the airstrip from safety.

"I was not sure whether I would survive or not," Majid said.

Now, Majid faces another uncertainty. He wonders whether his hours aboard that Pan Am flight will ever be recompensed. His appeals to the federal government have been unsuccessful.

"The commission has held that in order for a claim to be compensable, the claimant must have been a national of the United States," Foreign Claims Settlement Commission attorney Jack Guggenheim wrote in a letter to Majid.

What weighs on Majid's mind are reports that the U.S.-Libya settlement is being shared by noncitizens as well. If the funds are restricted to the estimated three dozen U.S. citizens aboard that flight, so be it, Majid said. But if they are available to noncitizens, then they should be distributed fairly.

"I became a victim twice," Majid said. "Once at that time and now again due to the system. I'm still hopeful that America will take care of this injustice."

Alyson Heyrend, spokeswoman for Rep. Jim Matheson, said the Utah Democrat's office looked into Majid's case. Although it was true that compensation had been given to noncitizens, she said it was awarded "in error and in violation of the statutes and rules set forth by the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission."

Now, with the change in Libya's government, Majid hopes that justice will come to every passenger — citizen or not — aboard Pan Am Flight 73. Perhaps a new government, he said, will help repair those old wrongs.

Pan Am 73: A look back

On the morning of Sept. 5, 1986, four men wearing security uniforms stormed the stairway of Pan Am Flight 73 with assault rifles, grenades and plastic explosive belts. Flight attendants managed to alert the cockpit, allowing the pilots to escape through an overhead hatch. With the plane grounded in Karachi, Pakistan, a 16-hour stalemate ensued during which an American was executed. When the plane's power failed that evening, the hijackers turned on the passengers, firing rifles and lobbing grenades into a crowded cabin. Many passengers escaped through a side door, dropping nearly two stories onto the tarmac. Twenty people died that day and more than 120 were injured. The hijackers were arrested, sentenced to death and later released.