This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Salt Lake City has not elected a Mormon mayor in nearly 30 years.

But during those three decades, Utah's capital has maintained a majority of Mormons on its City Council, usually five seats to two, sometimessix to one, and occasionally, seven to zip.

Most council members are moderate, even progressive. Yet popular LDS councilmen who made mayoral forays flamed out — spectacularly.

This pronounced political dichotomy surprises some. Do city voters suffer split personalities? Are the outcomes in these nonpartisan races simply a coincidence? Or is something deeper and manifestly religious at play in Salt Lake City politics?

Former city officeholders and politicos argue the dynamics are different between district races and citywide contests. But, they add, there is something more straightforward: No Mormon gunning for mayor since the mid-1980s has had the "right" politics — meaning they weren't far enough "left."

"A progressive, LDS person right now can win in the city. There's no question about it," contends Deeda Seed, an "extremely progressive" former councilwoman and an agnostic. "They haven't stepped up to run yet.

"In the mayor's race, it's been about the politics of the person first," Seed says. "There are religious bigots out there, but that is not the thing that drives elections here."

—

Mormon majority • Dating back decades, the makeup of the City Council is the best example of religious tolerance in Utah's liberal capital.

Mormons have long enjoyed healthy majorities in City Hall's legislative branch despite the fact that Mormons are now a minority in the headquarters city of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

"It illustrates that Salt Lake City residents aren't necessarily caught up in labels," says Jill Remington Love, current council chairwoman and a Latter-day Saint. "Mormons are voting for non-Mormons, and non-Mormons are voting for Mormons. Otherwise you wouldn't have that dynamic."

In 2001, when Eric Jergensen ran for a council seat from the Avenues — while serving as an LDS stake president — observers warned him his bid was doomed, especially since his District 3 predecessors were non-Mormon.

"People said to me, 'There's just no way you can win, because you're Mormon, a stake president and a Republican,' " Jergensen recalls. "But we did win. We didn't talk about labels; we talked about issues."

What's more, city polls showed the council's approval rating during Jergensen's two terms never dropped below 80 percent. And during five of those years, six of the seven members were Mormon.

"The idea that Salt Lake City residents will not vote for a Mormon," Jergensen adds, "is really highly overblown."

Another factor, culturally ingrained, helps explain the council's Mormon mathematics. Latter-day Saints are encouraged to engage in their neighborhoods, community groups and political races, though, Jergensen stresses, they are not directed how to vote.

"It's probably why there's a greater percentage of Mormons who run."

And once they do, they enjoy built-in bases of support in their LDS congregations, or wards. Indeed, the church serves as the chief organizing element, according to Jim Gonzales, a veteran political consultant who has worked on two mayoral races and a council campaign.

"In [council] elections, it's the wards that show up, unless there's some overriding issue that pushes people to the polls," Gonzales says. "It's the epitome of [late U.S. House Speaker] Tip O'Neill's 'all politics is local.' "

The LDS Church, Gonzales adds, is a powerful communications tool. He recalls giving city candidates a list of 900 moderate, Mormon women to call, "because these people are going to talk on Sunday at church. It's the one place where people gather every week and receive some kind of message."

Seed seconds the premise that Mormon wards frequently play council queen and kingmaker.

"If you are active [in the religion], you come in automatically with a constituency you know — a network that's built in," Seed says. "It's just sort of a basic numbers game."

—

It's the politics, stupid • Faith aside, neighborhoods often get comfortable electing — and re-electing — one of their own. But it's crucial in blue-hued Salt Lake City that those candidates, Mormon or otherwise, are not too conservative.

"It's a nonpartisan election, but that's really superficial — it really is a partisan environment," explains Quin Monson, associate director of Brigham Young University's Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy. "The political and partisan dynamic really is what sets the agenda."

Monson notes it would "shock me if you had a bunch of Mormon Republicans on the City Council."

"The religious divide is something that creeps up when there's a big issue like, say, [the LDS Church's] Main Street Plaza. But when there's not a big issue, it's not that big a deal. It's a subtext of a partisan and ideological divide."

Council candidates emphasize they are asked about party and ideology on the stump, rarely about religion. And those views, according to Jergensen, hold the key.

"The politics of the Mormon candidates who win are palatable to the city," he says. "If you had a Mormon candidate who was spouting things that were nonsensical, I think they would lose. People are pragmatic enough that just because the moniker is there doesn't mean they have a cakewalk into the election."

Gonzales, who notes council contests hinge on the most motivated 30 percent of residents, says LDS voters see likenesses in family-oriented progressive candidates.

"Mormons view themselves as being well-educated, moderate folks who do things for the right reasons. For the most part, they are," he says. "Dave Buhler may have been the last gasping remnant of a conservative coming from the east bench. I don't know that you are going to have a lot of conservative, active Mormons elected to the City Council. That's changing rapidly."

Mayor Ralph Becker trounced Buhler, a moderate two-term councilman, in the 2007 mayor's race.

Carlton Christensen and Van Turner, the current council's most conservative members, are Mormons from the city's west side. Both would be considered political moderates in many Utah locales.

—

Monopoly on mayor's office? • 1983. That was the last time an active Mormon captured City Hall. But after leaving midway through his third mayoral term in 1985, Ted Wilson was succeeded by a Catholic, followed by a Presbyterian, a baptized-but-not-practicing Mormon, and now, a nonactive Episcopalian.

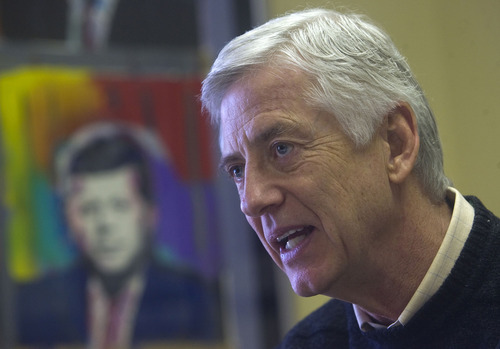

Stuart Reid, a Mormon and a former Salt Lake City councilman who lost his 1999 mayoral bid to Rocky Anderson by 15 percentage points, says that trend will continue.

"It's unlikely that you'll ever have a Mormon Republican mayor in Salt Lake City," says Reid, a GOP state senator from Ogden who ran for mayor as a Democrat. "And you may never have another mayor who is Mormon — regardless of their political affiliation. The Democrats, and those who are not LDS, view that office as the only substantial office that's left to them. So they make a real effort to get out. There is a real religious issue."

Love, the council chairwoman, and Seed dispute that. "In both Stuart Reid and Dave Buhler's case, it wasn't their religion" that cost them, Love says. "It was their politics."

So why do Mormon mayoral candidates have such trouble?

Besides the progressive nature of the city, Gonzales points to a wrinkle in the election process itself — that four of the seven council districts are not on the ballot in mayoral years.

"You take away half the motivation for those folks," he says. "Those church structures are great at that local level. But at the citywide level, it's the major organizations that take over."

Reid, who told Buhler he had "no chance to win," insists most Salt Lake City residents are predisposed to play the Mormon card at the polls.

"There are even LDS members where there's a sense that they want to reserve that for someone who is not Mormon," he says. "Popularity does not have a whole lot to do with it. It's definitely anti-establishment."

Perhaps. But Monson can point out an exception who breaks the mold.

"It wouldn't surprise me at all if [Democratic state Senator] Ben McAdams could succeed in a Salt Lake City mayoral election," he predicts. "He's got the politics right. He's unabashedly a liberal Democrat. And he's also a Mormon.

"There are not very many of them who have the right politics. I don't think Jim Matheson could get elected mayor of Salt Lake City."

Sounding off on SLC's Mormon/non-Mormon political split

"You've got a city where the majority of the residents aren't LDS but the majority of the [council] candidates are. In the local races, people don't worry about that."

Eric Jergensen

Former City Councilman

"It would shock me if you had a bunch of Mormon Republicans on the City Council."

Quin Monson

Associate director of Brigham Young University's Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy

"Salt Lake City as a whole ... won't elect somebody who's conservative, regardless of what their religion is."

Deeda Seed

Former City Councilwoman

"The [LDS] ward members may not be very familiar with their politics, but they know them as a person. On the other hand, the members of the church in Salt Lake City are also more progressive."

Stuart Reid

Former City Councilman