This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The square-jawed toddler holds a small baseball bat upright and waits for his father to throw a little red ball. The kid hits it and the dad chases it into the Jersey City streets, hustling back to the sidewalk where he and his 2-year-old repeat this exercise.

The Jims McMahon repeat this exercise day after day.

"This kid is going to be in the pros!" the elder McMahon tells his wife, Roberta.

"Don't say that," she warns him sternly.

The family moves to California. By the time young Jim is 9, he is the starting center fielder and cleanup hitter on a team of 12-year-olds.

"This kid is going to be in the pros!" the father exclaims.

"Don't say that," his wife says.

The father will always believe in the son, one of his six kids. He will move his family from California to Utah, where he will approach an unsuspecting high school football coach and say, "Do you have any quarterbacks?"

He will teach his son the fundamentals of the games he plays, he will skip out on work to attend practices. He will repeatedly say, "You play the game to win."

The son will remember this as a quarterback at a college he hates, where he will become, the father will say, the greatest player in the school's history even if the people there — he will spit the word "people" like it's a profanity — won't allow him into their hall of fame.

The square-jawed toddler will become a superstar, despite a reputation that makes his father cringe, and he'll never run out of bounds or slide to avoid a hit.

You play the game to win.

Even in the decade the son refuses to talk to the father, the old man will adjust the giant satellite dish in his yard to find the right coordinates to watch the son play.

He will be in the pros for 16 years and win two Super Bowls and the father will be so proud that one day, when they retire the No. 9 at the high school, the father will cry.

And the son will say, "I'm happy for my dad."

Son's biggest fan

The relationship between the elder Jim McMahon and his famous son has always been one of great admiration and pride. Mr. Mac, as he is known to his friends and family, asked LaVell Edwards when the BYU coach was recruiting his teenage son, "If Jimmy beats out your senior quarterback, will you start him?"

He was, after all, going to be in the pros.

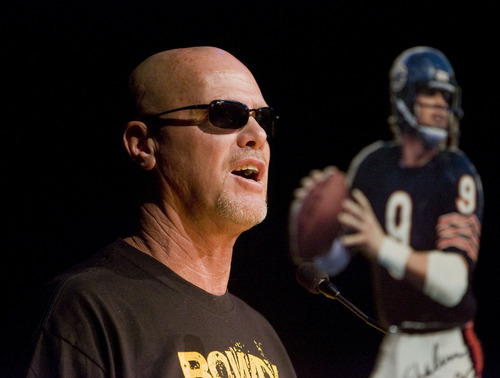

Thirty years later, after McMahon won Super Bowls with the 1986 Chicago Bears and the 1996 Green Bay Packers, traded in his mullet for a shaved head, and slipped into a philanthropic post-football career, his father still beats the drum for the quarterback.

In 2008, he launched a letter-writing campaign against BYU, from his home on a golf course in Mesquite, Nev., demanding to know why the school wouldn't allow Jim into its Hall of Fame (the long-held answer has been because he never graduated, a requirement implemented when the non-Mormon McMahon was playing for the Cougars).

"I can only hope," McMahon wrote, "that before I die this miscarriage of justice is corrected and Jim's jersey is retired and he is inducted into your Hall and his name is placed on the ring of honor on your stadium. If this is not done, then you should rename your Hall of Fame the Hall of Shame."

The son doesn't care.

"I tell pops, 'It's not a big deal to me,'" McMahon said. "But it is to him. You know, he's like, 'You deserve to be in there.' "

So McMahon this spring signed up for a correspondence math class. The textbook sits unopened on the table of his Scottsdale, Ariz., home. But he might finish it. If he does, he'll be one class closer to graduating from BYU and, presumably, the school's hall of fame in Provo.

It takes little prompting to get Mr. Mac fired up about the issue, even now.

"How can you have a hall of fame," the 75-year-old said, the gravelly words still glued together by a thick Jersey accent, "and have the greatest player ever to play at BYU not be in it?"

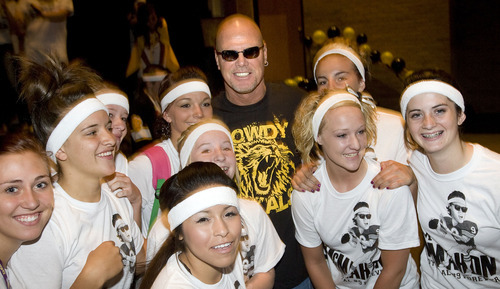

He wore a white T-shirt with a black-and-white cartoon image of his son throwing a football, wearing his trademark sunglasses and headband. The iconic accessories were all over Roy High on Sept. 16 for McMahon's induction into that school's hall of fame. Everyone wore them because, it seemed, they understood something BYU, in the elder McMahon's mind, refuses to acknowledge.

"It don't make sense," Mr. Mac said.

Getting punked

By the time he was 12, Jim McMahon was smoking two packs of cigarettes a day. He and his friends would break into the school and graffiti the walls. And they would smoke cigarettes.

He was old enough and tough enough to smoke but not yet savvy enough to know that two packs of cigarettes sitting out on the dining room table was a trap.

James F. McMahon, the father, coached the baseball team James R. McMahon starred on. It had won three straight championships and in the summer of 1971 was surely going to win a fourth.

Then Mr. Mac placed the smokes on the table and when one pack disappeared he kicked Jim off the team.

"I don't want a little a——— on my team," McMahon remembers his father saying to him.

In Utah last week for the retirement of his No. 9 uniform at Roy High School, McMahon said the summer he was denied the chance to play baseball corrected his path.

"Once he kicked me off the team and I realized I couldn't play anymore," McMahon said, "I straightened up."

Mostly.

McMahon always exhibited a hard-partying persona during his NFL years, going as hard off the field, it seemed, as on it.

You play the game to win.

He called himself "the punky QB" in the "Super Bowl Shuffle," the brazen music video by the 1985 Chicago Bears.

"I didn't like it," his father said. "It wasn't Jim. I thought he got a bum rap in the press about this 'punky QB' stuff and all that.

"I didn't write those lyrics," McMahon said simply, a golf-ball-sized wad of Skoal having long ago replaced cigarettes.

Mended relationship

The father and the son seem so happy now, so comfortable in this relationship. They get together a few times a year and play golf. The son travels the country playing in celebrity tournaments and the old man plays five days a week and has shaved his handicap to a 12.

In Mr. Mac's mind, there's no question who's the better player.

"Jimmy, of course!" the father said. "He can do anything."

They will live out the rest of their relationship this way, it seems. The father forever an advocate for his son, the son forever doing things that make his dad proud. Jim McMahon has traveled to Iraq to visit the troops, he has donated to St. Jude Children's Hospital, and is starting a literacy foundation in the name of his sister, Lynda, who died three years ago.

"I want that story told," Mr. Mac said, "the Jim McMahon that does so much for the children and the Wounded Warriors and so much for our military people. That's the story I want out there."

He doesn't want to talk about the days he and his son weren't talking. When he felt like the quarterback of the Super Bowl XX champion Chicago Bears blew him off the night of championship win.

McMahon said he stopped talking to his parents when he got married in 1982 to Nancy, whom he had four children with and remained married to for 28 years.

"I think my dad felt, he wanted me to be like Joe Namath," McMahon said. "Be a bachelor, do all this stuff. It didn't happen that way."

McMahon didn't think his parents treated his wife the way a daughter-in-law should be treated. So they didn't talk.

But those days are gone. They retreated to their Davis County hotel the night of the ceremony at Roy. The Royals lost to Box Elder in front of their greatest alum, but no one seemed to mind. McMahon drank beers and greeted his guests, most family or friends from the days at Roy. His father did the same.

They were back-slapping and happy. Just like a father and a son. James F. McMahon has never looked at James R. McMahon like the rest of the world does. His pride doesn't stem from his son's athletic success, it seems, just from the fact that he has had success.

"He's just one of the kids," Mr. Mac said. "He was no better than Mike or Rob or Lynda or Stacy. They're all equal as far as my wife and I are concerned. But Jim is Jim. He's a good kid."

And the father will run through the streets, chasing balls or whatever it takes, to be there for his square-jawed son.

boram@sltrib.comTwitter: @oramb —

Jim McMahon

Age • 52

Home • Scottsdale, Ariz.

Pro career • 16-year NFL quarterback with the Chicago Bears, Philadelphia Eagles, Minnesota Vikings, Green Bay Packers, San Diego Chargers and Arizona Cardinals. Won two Super Bowls.

College • BYU quarterback, 1977-1982. Winner of the Sammy Baugh and Davey O'Brien trophies and was two-time MVP of the Holiday Bowl.