This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Blanding • When Hank Stevens' family hunted under Bears Ears Buttes, they always honored the deer whose life they had taken and the place that nurtured it.

"We respect the animal where it dropped," said the Navajo tribal leader Monday while flying over the new Bears Ears National Monument in southeastern Utah.

"We do a little ritual where we leave the intestine, testicles and the antlers there. We only take the meat and the buck hide."

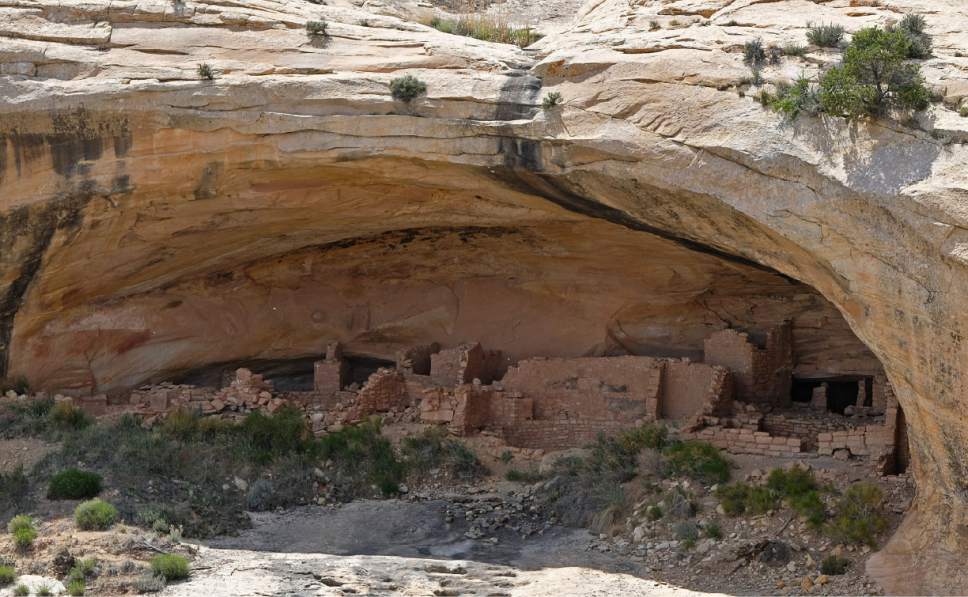

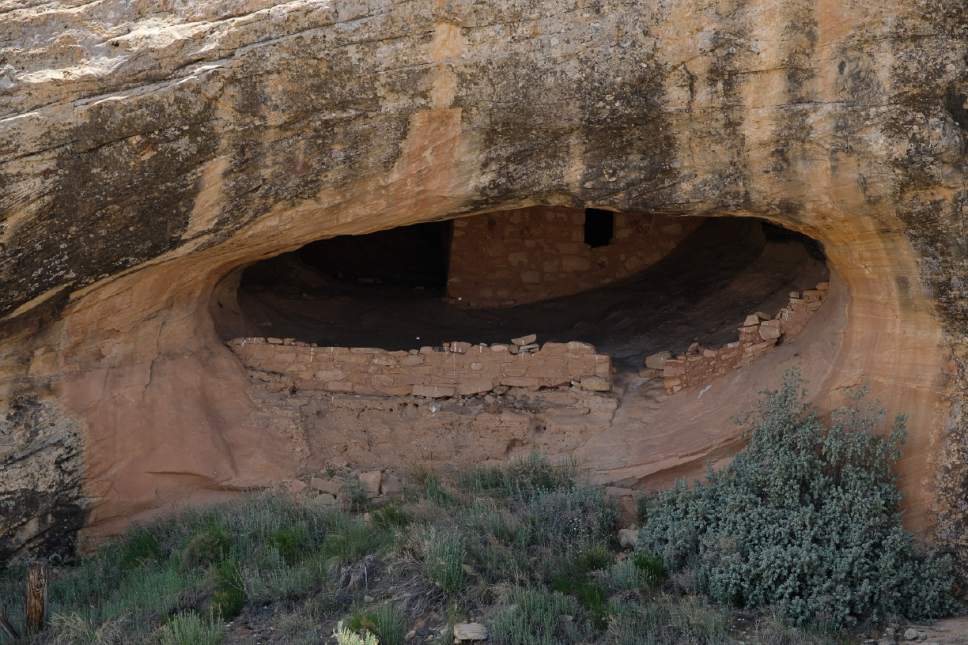

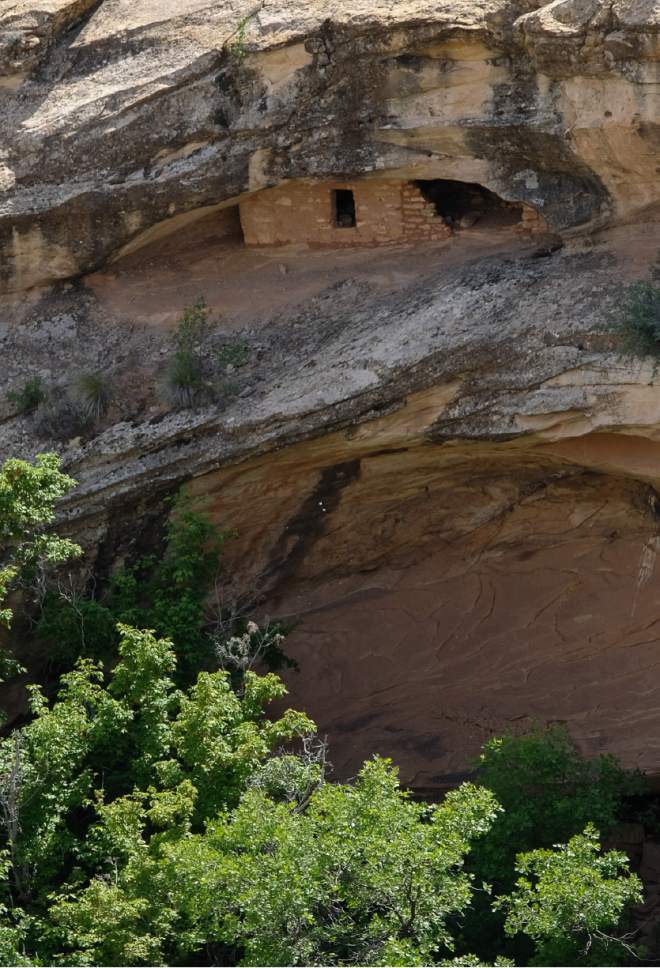

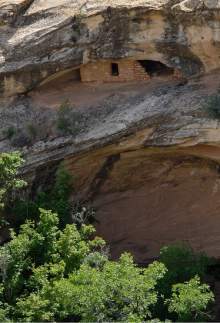

Below, sinuous canyons fell away from the juniper-topped mesas surrounding Bears Ears Buttes, the 1.35-million-acre monument's namesake and home to tens of thousands of sites left by ancestral Puebloans.

The sky view was also enjoyed Monday by Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke who is in Utah this week.

Under orders from President Donald Trump, Zinke is reviewing 27 large national monuments designated since 1996, starting with Bears Ears, which former President Barack Obama designated at the request of five tribes with ancestral ties to these public lands.

The designation has sparked an intense backlash from Utah's political leaders denouncing it as "federal overreach" and a "land grab."

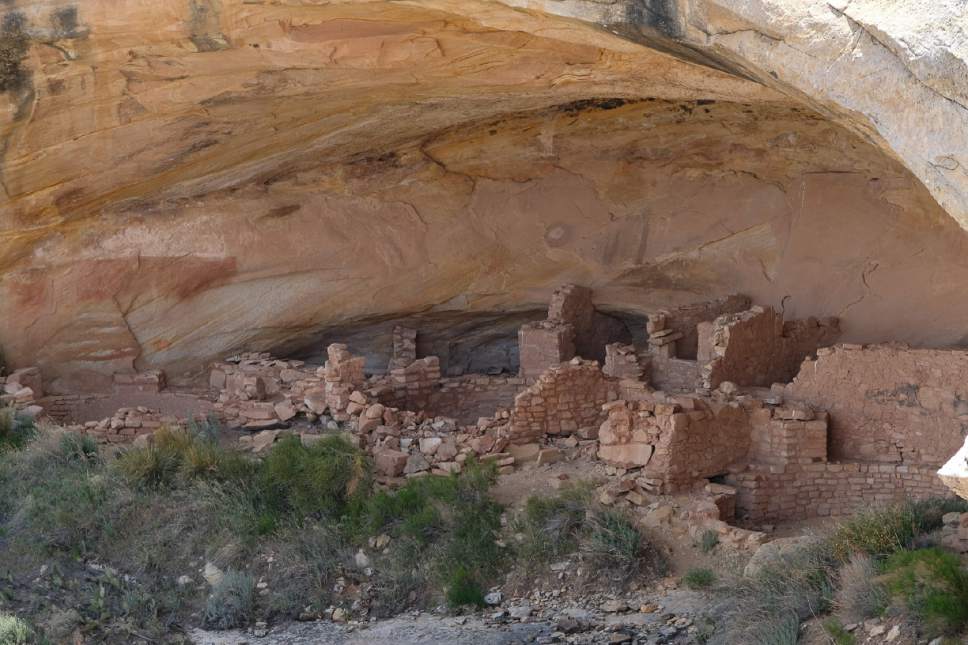

Joined by an entourage composed entirely of anti-monument politicians, Zinke flew over the landscape aboard three Army Black Hawk helicopters and later hiked to Butler Wash, a popular destination overlooking cliff dwellings left by ancient American Indians.

"It's been a while since I flew in a Black Hawk without people shooting at me," said Zinke in joking reference to his stint as a Navy Seal commander.

"The trip today verified it is drop-dead gorgeous country. No question about it," Zinke told reporters gathered Monday at the Butler Wash trailhead. "We want to make sure everyone's voice is heard. A lot of the anger out there in our country is local communities and states don't feel like they had a voice. Washington has done things that seem heavy handed without coordination."

Zinke's remarks echoed criticism of the monument designation leveled by Utah's top political leaders, including Gov. Gary Herbert, who joined the hike.

"We know you are going to take a good look at this with an open mind and unbiased attitude, and I know your challenge is to get some recommendations on what to do to bring us together and resolve some of these conflicts," Herbert told Zinke.

But many pro-monument Navajo, including Stevens, complain that they are being excluded from the discussion.

President of the Navajo Mountain tribal chapter, Stevens was among several members of Utah Dine Bikeyah, the grass-roots Navajo nonprofit that has long lobbied to conserve what it considers a sacred landscape, gathered at the Blanding Airport on Monday morning, hoping for a word with Zinke.

The new secretary, who has earned a reputation for respecting tribal interests as a Montana politician, gathered inside with state and local leaders who want Trump to rescind the monument. Bikeyah board Chairman Willie Grayeyes tried to enter but was barred by Utah Highway Patrol troopers.

"We are asking for equal time and it's not happening," said group member Woody Lee. "It happens all the time."

On Sunday in Salt Lake City, Zinke met with tribal leaders who support the monument, but his staff declined a formal meeting request submitted by Utah Dine Bikeyah. On the street outside the Bureau of Land Management headquarters, hundreds of Bears Ears supporters clamored for equal hearing and respect for tribal sovereignty.

Ute, Navajo and Puebloan tribal leaders are dismayed that the first national monument created at the request of American Indians could become the first undone by a succeeding president. But undoing or reducing the monument would not mean opening Bears Ears to extraction, Zinke said.

"Yes, of course the legacy and what I've seen should be preserved. The issue is whether the monument is the right vehicle," said Zinke, who was trained as a geologist. "What vehicle of public land is appropriate to preserve the cultural identity, to make sure the tribes have a voice and make sure you preserve the traditions of hunting and fishing and public access?"

He said he is concerned about how monument rules would restrict land uses.

"If you live in the county, making a living is a good thing, too," he said. "Having your access limited is a problem."

Zinke is scheduled to continue his tour Tuesday with a ride through Bears Ears Buttes on a towering 17-hand horse provided by San Juan County Commissioner Bruce Adams.

He will conclude his tour Wednesday in Kanab, where he will review the 1.9-million-acre Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, designated 20 years ago by President Bill Clinton.

At the Blanding airport Monday, Adams, a Monticello rancher, passed around white cowboy hats emblazoned with the Trumpian slogan: "Make San Juan County Great Again."

"By getting rid of this layer of this monument, we can get back to the greatness of where we were," Adams said.

He and other monument critics fear restrictions that come with monument status on the 1.35 million acres west of Blanding will thwart economic development, impede public access and undermine local schools by disrupting possible revenue sources.

On Monday, local monument opponents, including American Indians, presented their case for erasing the monument at the Utah State University Blanding campus and later at a park, where Zinke briefly joined them.

"We are concerned by the divisiveness created in our county among the people," Adams said. "We want to see the people unified and want to see them brought together and work together to make San Juan County great."

But Lee, the Bikeyah member, had a different take on Adams' idea of greatness.

"It's great as long as Indians don't say anything," Lee said.

bmaffly@sltrib.com Twitter: @brianmaffly

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. He can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713.

Twitter: @brianmaffly