This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

John came here for a different life, and he quickly found one.

The lanky New Mexican had befriended a Utah man while serving time in a Texas prison and — breaking his own rule — trusted him. On that pal's advice, he'd booked a flight and touched down in Salt Lake City expecting to be pointed toward steady work and sober influences. But the friend hadn't shown.

In fact, the man's sum charity had amounted to texting John an address near the 210 S. Rio Grande St. homeless shelter, where John could buy some heroin that would chill him out.

"Who do I talk to?" John had asked.

"Don't worry," the man said. "You'll find it."

John was a longtime user, but the scene he encountered there was strange to him. Dealers paced among users and brazenly asked "Black or white?" meaning "Heroin or crack cocaine?" John was cited within an hour. A month later, he'd been criminally charged five times and contracted hepatitis C. This was different, all right. This was chaos.

—

And that was the context that Shawn McMillen, executive director of First Step House, was missing last fall when he first saw John at a local treatment center, his face affixed with a broad, toothy smile on the same day that he'd been picked up by Salt Lake City police.

"I'm thinking, 'Is this guy OK?' " McMillen said.

Did John need water? No.

Was he feeling all right? Yes.

He still had that perplexing smile, though.

Was he sure?

"Yeah, I feel like God gave me a gift today," John said.

"I started crying just as soon as it came out of his mouth," McMillen said. "Just the way he said it, the sincerity, and the smile on his face."

Today, John is clean, employed and seeking housing. He was one of four First Step House clients who recently spoke to The Salt Lake Tribune about the residential treatment they received through Operation Diversion, a Salt Lake County-funded law enforcement initiative to open beds for drug users.

The Tribune agreed to omit their surnames so they could speak candidly without diminishing their prospects.

Although Operation Diversion seemed heaven-sent to success stories like John, the jury's still out on the overall effectiveness of the program's first act: three sweeps in which police gave drug offenders the chance to instantly begin inpatient treatment. Of 68 people diverted to treatment in those sweeps, six had graduated and 54 had absconded by mid-May.

Their free beds have been filled by people who self-reported to Salt Lake City Police Department social workers at 511 W. 200 South and received a chance to bypass a six- to nine-month wait for other county-funded beds.

The walk-ins are sticking with treatment at a higher rate, but now Operation Diversion — with uncertain long-term funding — has a growing waitlist of its own.

—

'The weirdest arrest ever' • Ben's early impression of "The Block" — as users know the area where officers wrote more than 65,000 reports in 2016 — was that it was "perfect, honestly."

His path to the vicinity of the Rio Grande shelter was a common one: from meth to prescription pills to heroin, until his parents tired of his abuse and drove him there.

"At first, it's scary, but after a little bit, it's normal," he said. "Seeing people get beat up, shooting drugs everywhere, it's normal."

Ben met Joshua, whose wife left him because of drug use in 2013, while they were staying at the Rescue Mission of Salt Lake, and Joshua began to share some of the heroin that he earned holding drugs and cash for Honduran cartel workers.

Both remember a conversation they had one low day, after cooking up some subpar heroin. Ben had needled him for covering a used syringe with some dirt. Joshua had stared at his damaged veins.

"You know we're going to die down here, right?" Joshua had asked.

"Yeah, of course," Ben said. "That's the plan."

Jail stints had done little to interrupt their habits, though the county jail offers longer-term inmates a 90-day treatment program that has just a one- to two-week wait.

Ben said detoxing in the county jail is only about a third as difficult as willfully detoxing, because "if you know you can fix it, your brain will make it worse for you." That means jail-induced sobriety "doesn't count," he said. "You feel healthy, but you don't feel like you accomplished anything."

The First Step House clients said that often, when addicts are released, they will board a bus for the shelter without having established a supportive network or having addressed the underlying causes of their addiction.

Or, when prosecutors fail to file charges within 72 hours, a heroin-addicted inmate will be freed at the peak of dope sickness, when "you're very desperate and you will do whatever the hell you've got to do to get high," Joshua said.

The day Joshua was apprehended and fast-tracked into residential treatment, rather than jail, he'd resorted to stealing cash from another prospective customer. When that man had pleaded that he'd split his heroin if Joshua would just give him the money back to buy it, Joshua had accepted the offer and apologized, he said. He needed to get help, he'd told the man.

It was minutes later, spotted by police cooking up the dope nearby, that he got his wish.

Ben was caught smoking spice the very same hour, and the two friends ran into each other as they were evaluated for treatment near police headquarters.

They'd been offered sack lunches and candy, and introduced to legal defenders. "It was the weirdest arrest ever," said Ben, who was placed on methadone treatment within four hours. "They were being nice."

By 10 p.m., Ben had checked into First Step House's residential treatment center, where he took a shower and went to bed.

He and Joshua have since graduated from the program and found housing. They're employed, and both hope to advance their education.

Ben said he recently eyed a balloon of heroin on the ground, and even though he felt a wave of anxiety wash over him, he said, it wasn't the "explosion" he might have once felt.

"I could get high now with no consequence, but I don't want to."

—

Living on the list • The three fall sweeps married the best parts of jail and voluntary treatment. Users would make their own choices and take pride in their sobriety — it would "count" — and they would begin treatment right away, without first enduring another half-year of being asked "Black or white?" on The Block.

Although $1.4 million in expected city and county funding would keep those treatment beds open through 2017, they're no longer available for entry en masse.

About 120 walk-ins at the Salt Lake City Police Department's Community Connection Center are waiting for a bed, up from 90 in March. An average wait time isn't available, but residential treatment typically lasts about three months, and some beds remain occupied for longer as clients encounter setbacks or struggles to obtain housing.

"What we've essentially done is created another list," McMillen said. "There's the Salt Lake County list, and now there is the Project Diversion list."

Salt Lake City police social workers — there are now eight after a recent hire — have teamed with providers to identify alternate funding streams for some people seeking treatment. But there is a glut of single men, McMillen said, for whom there are few alternatives to the city and county lists.

To escape the temptation of the shelter, some of them turn to short-term care facilities like Volunteers of America's (VOA) downtown detox center, where clients are turned out every two weeks and must wait a full day before readmission.

Demand has long trickled back down to the VOA's detox center from the brimming residential treatment centers, and addicts often have sat on the bench outside its front door, waiting for a vacancy.

"Most people go out and use" during the 24 hours they're turned out by the VOA, said Russell Gregersen, in his sixth week at the facility. "They've only been clean two weeks, and they're just starting to feel normal, and you get out there and it's just like, 'What do I do now? Where do I go?' "

Clients are meant to re-enter the facility in need of detox services — to "go in dirty," as they call it — but they aren't drug-tested. There's nothing to stop them from pretending they used, and Gregersen implied he's used that tactic. He expressed no remorse: Some clients, he said, occupy the facility's beds with no intention of getting clean.

During 30 years of drug use, Gregersen has entered residential treatment five times and even graduated once. But he attempted suicide after a mid-March relapse.

"I didn't want to exist anymore," he said. "I was tired of fighting using and I was tired of not using, and I just gave up."

For now, Gregersen attends group meetings and fiddles on a guitar while he waits for a chance he feels ready to capitalize on. He calls the Community Connection Center every day.

—

'It's going to continue to be a problem' • The future of Operation Diversion rests in its appraisal by policymakers.

The available measures of its success are imperfect, given the program's lack of precedent, the unknowable future of an addict's recovery and the vagueness of notions about the program's societal cost-benefit offset.

Salt Lake City Councilwoman Lisa Adams asked Police Chief Mike Brown last week what to make of the 54 out of 68 people who left residential treatment after the sweeps last fall.

Brown has pointed to the far better success rate among voluntary clients who've obtained treatment through the Community Connection Center. More than half — 113 of 220 — who secured either inpatient or outpatient treatment through the center have thus far stuck it out.

McMillen said recovery, for many addicts, takes multiple tries. The men entering treatment at First Step House are typically on Rounds Three or Four.

Jason didn't buy into First Step House the first time, in 2002. He'd been "on the fence" and sought out like-minded residents to commiserate with. This time around, he said, he made positive connections and found purpose in a local sober softball league.

But Jason waited only 12 days for a spot after walking into the Community Connection Center this January. If he'd had to wait months, he said, "I could be out using again, and I would've probably been back in jail."

Noella Sudbury, Criminal Justice Advisory Council coordinator for Salt Lake County, said that while the demand for publicly funded addiction treatment is nothing new, the crush of Operation Diversion bed-seekers has at least shed new light on the shortfall.

"Absent more dollars for treatment, it's going to continue to be a problem," she said.

The county will know by July 1 whether the state has accepted a request for $4 million of $6 million in grant money set aside by the Legislature for the Justice Reinvestment Initiative — which lessened penalties for drug crimes with the promise of eventual treatment dollars that would reduce demand for criminal activity.

If the state holds the county to its formulaic share of that grant money, about $1.9 million, the future of those 63 Operation Diversion beds is unknown.

The elephants in the room are Utah's unresolved small-scale Medicaid expansion — $100 million that the state can't spend, as intended, on its most at-risk residents — and the region's dearth of affordable housing.

Joshua said that if treatment beds were unlimited, about half the users on The Block would leave it immediately. Maybe a third of those staying would accept a second offer later, he said.

"And then the other ones are the people that have pretty much made the choice that that's where they want to be, that's where they want to die, and they're OK with that."

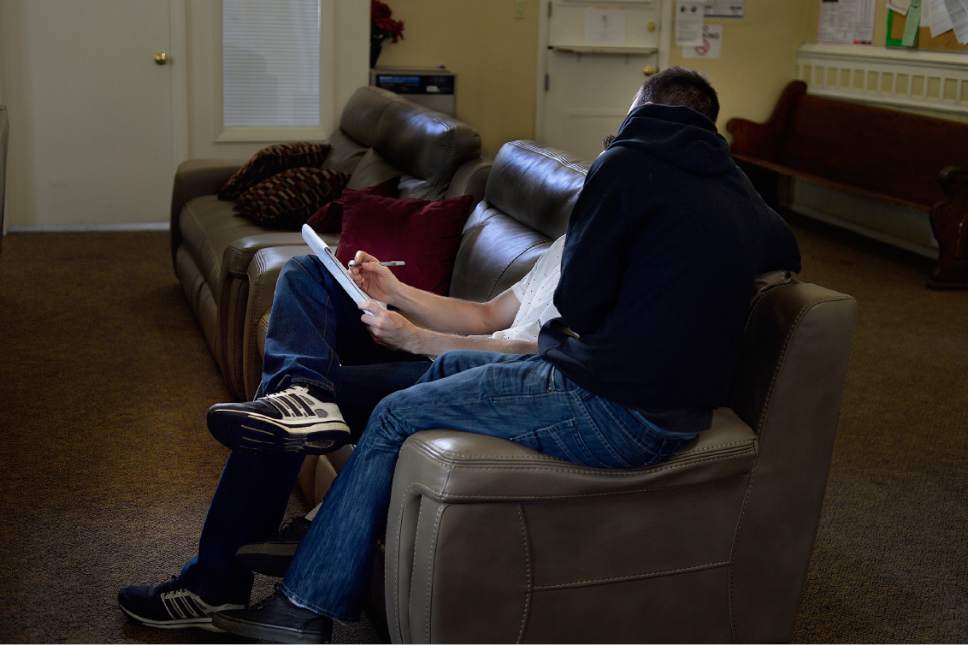

Joshua, Ben, Jason and John all projected a sense of seriousness and duty as they testified about the virtues of Operation Diversion, each listening intently and nodding supportively as the others spoke.

Three of them were also in small groups that recently welcomed Brown and City Councilman Derek Kitchen to the old Mormon meetinghouse on the corner of 400 North and Grant Street.

John began his story by saying his treatment has "done everything that I thought was almost impossible in my life."

He ended it by flashing that big, bright smile.

Twitter: @matthew_piper