This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

South Salt Lake is stuck between a rock and Granite.

Nearly three months after residents, by five votes, rejected a $25 million bond to buy and renovate historic Granite High, city leaders still harbor hope of purchasing the property before their June 30 lease expires.

But that plan continues to polarize a city whose residents desperately want to reboot South Salt Lake's image but don't want a tax hike to get there.

"A lot of people still feel pretty strongly that Granite should be something prominent in this city," says Sharen Hauri, the city's urban design director. "But in this economic climate, there's not a lot of ways to pay for it."

Complicating matters: The sales-tax-strapped city has already invested roughly $450,000 into the property, which could not be recouped if it does not buy the 105-year-old school.

For years, City Hall studied what to do with the vacant but venerable four-building campus. Officials promoted the bond as a way to transfigure the 27-acre property into a civic centerpiece where students, seniors, artists, recreationists and families could gather in a mix of public amenities and open space.

On a glossy mailer, advocates warned that, if the bond failed, "the city will terminate the lease agreement." That thinking has since changed, but so has the vision for Granite.

"We respect that vote," Hauri explains. "Even if it had won by five votes, we wouldn't be going out for a bond for $25 million because there wasn't enough consensus."

Now, Hauri says, the "bare minimum strategy" is to buy the property for the $8.7 million asking price, then secure partners to help fund upgrades.

Possible uses include a charter high school — the city has no high school — a preschool, or both. City bosses warn that if they don't snag Granite, it could be sold and then converted into housing projects or some commercial use.

Hauri says roughly half the residents favor the $8.7 million purchase, half want to pay less — but most hope to use "other people's money." There also are limitations on using tax-exempt bonds for the purchase.

"The school is a historic treasure that deserves preservation. Allowing it to fall into private hands is too risky," resident Julia Light wrote on the city's online forum "Open Town Hall." "Our community needs a centralized gathering spot that we can be proud of, and open space is an extremely valuable and highly desirable asset. I agree that any increase in property taxes adds to the growing burden in these rough times, but I strongly believe that this is worth it."

Resident Debbie Snow is less enthusiastic, signifying the election divide that still simmers.

"Even if South Salt Lake could find funding to purchase the property without using a bond process, I still think it would be a mistake to have the city use all 27 acres of the property," she writes. "That property should be purchased, at least in part, by private developers who can build homes in the area. South Salt Lake needs more rooftops. Nothing is going to re-invigorate the area more than more residents — people who own their homes, who will pay taxes, and patronize local businesses."

The city has long suffered from a condensed sales-tax base, sullied by sewage-treatment plants, Salt Lake County jails, freeways, bus barns, light-rail garages and other properties that don't fill the public purse. Mayor Cherie Wood campaigned on revamping the reputation. And the southern neighbor to Utah's capital has a new logo: "City on the Move."

Progress is planned — and partially paid for. The federally funded Sugar House streetcar will bisect the edge of town, stopping at the Central Pointe TRAX station. And a massive redevelopment to greet the trolley is planned between State and Main streets, featuring new housing, shops and eateries.

Still, resident Forrest Webster insists the city continues to suffer as a "tax-free hub" for penal facilities and public buildings.

"Would I be too bold to say that our community has failed to come together with a vision of our future?" he writes. "Overall, we don't compete well with the surrounding cities and governments and, as such, have been picked apart."

Webster voted for the bond but says the $7-a-month cost was rejected "due to the burden the community already bears from the financial and civic culture."

Construction worker Bob LeMone, who lives two blocks from Granite, argues the city's purchase strategy — particularly the nonrefundable "earnest" money — has essentially backfired.

"Because the city signed this lease-purchase agreement seven months before the election, the city officials are caught in the middle," he writes. "If they do not buy Granite, they will forfeit the taxpayers' money. If they do buy it, they will be ignoring the voters and the election. Do you think our democratic process should work this way?"

Despite the divide, Utah Heritage Foundation Executive Director Kirk Huffaker insists there should be a deeper consideration. Granite is a valuable community asset, he says, with historic characteristics that are rare by both South Salt Lake and most small-town standards.

Those characteristics, he adds, "should not be discounted as to the benefits they can generate for the community for decades to come." —

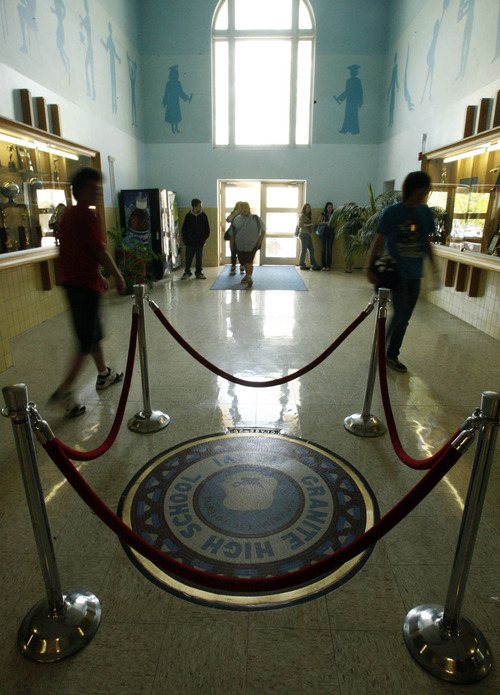

Granite on the block

South Salt Lake faces a June 30 deadline to buy the former Granite High after voters in November rejected a $25 million bond by five votes. Residents remain sharply divided about whether to spend tax dollars on the deal. But if the lease expires, the city would lose nearly $500,000 already invested in the historic school.