This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

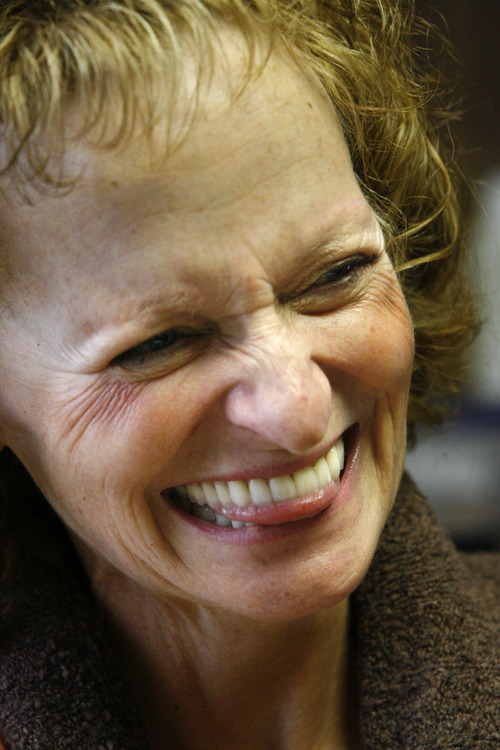

Debra Brown — found innocent of murder and freed after spending nearly two decades in prison — says time stood still for her while the rest of the world, and her children, grew and changed.

"Try to imagine being frozen, then waking up 17 years later," Brown says.

Coping with her new-found personal freedom has been a daunting novelty.

"Getting up that first morning and having choice," she adds. "I was blown away by a lot of things. Just figuring out little decisions. I was in my room for over an hour changing my clothes because I could."

It's been nine months since Brown, 54, was released from the Utah State Prison by 2nd District Judge Michael DiReda, who found her factually innocent of the November 1993 shooting death of her friend and employer, Lael Brown (no relation).

Brown's murder case was the first to be revisited under a 2008 statute allowing convicts to challenge the facts of their cases when new evidence is discovered, even if there is no new DNA evidence.

Brown wants to move on and leave her past behind. But the Attorney General's Office is challenging DiReda's decision to set her free, questioning whether the judge had sufficient proof of "clear and convincing evidence" to exonerate Brown.

Tuesday is the deadline for the AG's Office to file their appeal with Utah Supreme Court. The AG's Office has said they do not want Brown returned to prison if they win the appeal; they merely want prevent the establishment of a "fatally flawed" legal precedent.

Brown remains apprehensive. "I have nightmares where I wake up and I am back in that prison," Brown says.

Starting over:

Brown, the mother of three and grandmother of seven, has been reacquainting herself with the world she left behind: from the mundane activities of riding a bike or taking a bath, to the more challenging adjustments of finding her role in the lives of her grown children.

Playing with her granddaughter recently, Brown turned to see her youngest daughter, Alana, watching them and crying.

"What's the matter, baby?" Brown remembered asking.

"I'm just seeing what kind of mom you would have been," her daughter responded.

Such moments break your heart, Brown says during a recent interview at her home in Richmond.

Brown suddenly stops talking, distracted by a noise she doesn't immediately recognize.

Then she realizes it's just the refrigerator and smiles.

She resumes, saying: "I thought I was going to get out and pick right back up where I left off. And that's not realistic, but I did think that at the start."

Instead, she says, her new life has been one reality check after another.

When she went to prison her children were 11, 12 and 17. Now, grown and married, they have children of their own.

"They did what they had to do. They moved on because it is the only thing they could do. I'm not the mom they knew," Brown says. "So it's this total stranger knocking at the door trying to get back in their lives."

The family interactions are awkward at times. In a way, she has learned that interacting with strangers is easier.

In prison, you numb up, you keep boundaries as a survival mode and you really don't get close to anybody because you can't, Brown says, who beat breast and cervical cancer while incarcerated.

Now, as a free woman, Brown realizes what that once necessary survival mechanism has cost her.

"I forgot what it is like to have family and how to deal with people that you love," she says.

Brown's biggest fear is that they will never become a normal family. And just as much, she hopes for the comfort of not feeling like a visitor.

"I want it now — I feel like I waited 17 years for it — let me be the mom and grandma," Brown says, adding how difficult the idea of patience is to her. "But I can do this. We have fought bigger battles than this."

Baby steps:

After her release, Brown moved in with her brother, David Scott, who lives in Idaho, where she says her first two months were all about making baby steps.

She's been on a learning curve when it comes to technology. During one of her first trips to the supermarket, she stood for a while waiting for a cashier, unaware she was at a self-service station.

But she now has an e-mail account and has used Skype. Then there is the texting, which she doesn't like because it's so impersonal.

Riding her bicycle on country roads for hours at a time became a way to ease the anxiety of all things new.

And she tries to never miss a sunset or a sunrise.

One of her first outings after being freed was with her brother, who took her fishing to a spot he had often talked about.

She refers to her brother and sister-in-law as the people who carried her weight, watching over her children and grandchildren in her absence.

"They have been filling this void all these years," Brown says. "I'm the newcomer into this and I have to take whatever it is that they [her children and grandchildren] can give me and be grateful for that."

She faced another reality check once she set out to find a job.

Her first attempts were not successful. "I went through a lot of doors being slammed shut," Brown says, recalling her feeling of doom when she found out that "not even Deseret Industries" would hire her because of her prison record.

Job applications posed the question, "Have you been convicted of a felony in the last seven years?"

Technically, the answer is no, Brown believes. "However, you've got to be honest," she said. "So I wrote, 'Yes, will explain during interview.' "

When she did get interviews, she said, potential employers knew about her conviction, but nothing about her exoneration.

"That devastated me," Brown says.

Last summer, she moved to Richmond, in Cache County. It helped that more of her family live in the area.

The area also had more employment opportunities, and she finally landed a full-time job in the deli department of a grocery store.

What's next?:

Brown, who has compiled a long to-do list, recently checked off being baptized.

She had given up on the prospect after an initial rejection because of her pending court appeal. "I was pissed," Brown says remembering her conversation with an LDS Church stake president and feeling like she was still being judged.

Months later she got better news from a church official in her new community.

A bouquet of flowers from the recent baptism ceremony sits in the kitchen table of her aunt and uncle's home.

In an effort to figure out what comes next in her life, Brown has planned a week-long trip to northern Idaho. Her car sits in the driveway packed and ready to go.

"Everyone has aspirations to do something really great," Brown says. Then, referring to her own sense of the future, adds, "I just don't know what that is. I wish I knew."

After 17 years of following others' rules, she says, she has no practice steering her own course.

As she finishes her thought, the phone rings, presenting her with yet another decision to make.

It's her daughter, Alana. Brown's granddaughter is sick. She speaks for several moments taking in the information and gauging the gravity of the situation.

"Gosh. I probably should stay here and take care of the little one," Brown says to herself after getting off the phone. "Dang it. I'm just mixed about this whole trip now. I'm not sure what I should do."

rorellana@sltrib.com —

The case so far

At Debra Brown's 1995 trial, prosecutors claimed she shot and killed her friend and employer, 75-year-old Lael Brown, at his Logan home at 7 a.m. on Nov. 7, 1993 — the only time when Debra Brown had no corroborated alibi. She was convicted of murder and sentenced to prison for up to life.

Rocky Mountain Innocence Center attorneys, who began working on Brown's case almost a decade ago, last year presented witnesses who said they saw Lael Brown alive after he had supposedly been killed. One witness was on the defense's witness list but was never called to testify.

Second District Judge Michael DiReda found Debra Brown "factually innocent" of the homicide and ordered her released from prison on May 9, 2011.

The Utah Attorney General's Office initially said they would appeal DiReda's decision, but Attorney General Mark Shurtleff quickly countered that there would be no appeal. A week later, Shurtleff reversed himself, saying an appeal was needed to prevent establishment of a "fatally flawed" legal precedent.

Tuesday the AG's Office is expected to file its appeal with the Utah Supreme Court.

The AG's Office has questioned whether DiReda had sufficient proof of "clear and convincing evidence" regarding Brown's innocence. —

HB307 • Factual Innocence Amendments

Sponsor Rep. Brad Dee, R-Ogden • Dee says his bill "tightens things up a little" in Utah's 2008 Factual Innocence statute by clarifying certain language.

Scott Reed with the Attorney General's Office said the clarifications ensure that any evidence brought to a factual innocence hearing is clearly new and not a rehashing or second-guessing of the trial evidence.

Opponents of the bill say the amendments to the bill leave out language that gives a judge the discretion to consider evidence that should have been found at the time of the trial, as well as new evidence.

The bill, as is stands, could negatively affect cases like that of Debra Brown, where a judge relied on both types of evidence, opponents say. On Friday Rep. David Litvack, D-Salt Lake, proposed adding language that addresses the opponents' concerns.

The bill is currently on hold on the House floor.