This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Heber Valley • Paula Trater's business card says she is a biological technician for the Utah Reclamation Mitigation and Conservation Commission.

But she's really "the frog lady."

It's a simpler, more affectionate moniker — one fishers and other frequent users of the middle Provo River bestowed on her sometime during the past 20 years when she was wading, walking and poking with sticks as she looked for frogs in the Heber Valley.

"It is much easier to remember frog lady," she said on a recent rainy morning during her annual excursion to count Columbia spotted frogs.

Trater works with biologists from the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (DWR) along the middle Provo River to monitor the population of the native Utah frogs.

Columbia spotted frogs are one of the state's 15 native amphibians and one of the five considered a Utah sensitive species. The spotted frog, which ranges from northern Utah to Millard County, has been petitioned for federal protection on the endangered species list in the past, warranting the sensitive species status.

A multiagency conservation agreement for the Columbia spotted frog in Utah, the southern extent of the frogs in the United States, serves as a guideline to "ensure the long-term persistence" of the species within its historic range.

"Frogs are a very important part of the ecosystem. Even if you are not a big fan of frogs, you may be a fan of something that eats frogs," said Chris Crockett, a native aquatics project leader for DWR. "They also do people a great service by eating insects like mosquito larvae."

Amphibians also have been called an "indicator" species: If they're healthy, chances are the environment is, too. Frogs, toads and salamanders are a sensitive bunch; minor changes in their surroundings can wreak immediate havoc on localized populations.

"Research indicates that many of the compounds which cause health issues in amphibians cause similar issues in humans. One could think of them as a proverbial early-warning system or an ambassador of water quality," Crockett said.

Frogs are important for another, more personal reason.

"You would be surprised how many people tell me how much they enjoy hearing frog calls," Crockett said. "Many relate the sound to a childhood experience and find the sound relaxing."

Hearing frogs may be pleasant, but finding them often is not. They blend in with their natural surroundings and, because they can absorb oxygen through their skin, can remain submerged as long as they have enough in their blood.

Adult frogs most often are seen in the spring, when they congregate to lay and fertilize eggs. But even then they can be hard to spot, so precise counts are virtually impossible.

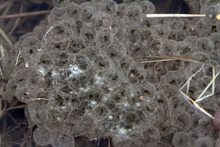

Biologists instead determine how the population is faring by tallying fertilized egg masses left by the frogs.

Trater became a frog counter, working for Utah, in 1992 as work on the Jordanelle Dam began on the Provo River. She said the frogs seemed a little desperate to find places to deposit their young.

"After the dam was constructed," she said, "there were eggs in the tire ruts left from the machinery."

Biologists worked to determine Columbia spotted frog numbers below the dam before it was completed to track how the reservoir and, more importantly, how the restoration work that took place on the Provo River below it affected the population.

The commission hired Trater in 1999, when work on the Provo River Restoration Project between Jordanelle and Deer Creek Reservoir began. The Provo River had been channeled into a fast-flowing water-delivery system rather than a meandering and natural river with wide bends and occasional wetlands along its course. The project returned it to a river and not an irrigation canal.

It took time for Trater to learn the ins and outs of finding egg masses, but there was no doubt more of them sprang up after the Provo restoration began.

"The numbers were pretty low, around a few hundred, but we were up to 400 to 500 in the late 1990s," she said. "We had more habitat coming online, and there were just more places for them to lay eggs. I remember seeing eggs in places where the land had been dry just two weeks earlier."

The highest population ever counted in the Heber Valley came last year when 1,091 egg masses were tallied, compared with an average for all years of 664 masses.

While the Heber Valley population appears to be thriving, some across the state are holding steady — such as the frogs on the upper Provo River above Jordanelle — and others may be dwindling.

"We have seen a decline in some localized areas," said Mark Grover, a native aquatic biologist with the DWR. The loss of wetlands has been a factor in some cases. Populations also fluctuate with the changing weather from year to year.

Other threats to Utah native frogs include amphibian diseases and non-native species — such as bullfrogs — that compete for habitat with and feed on smaller frogs.

Grover said Columbia spotted frogs seem to be holding on in Utah, but he emphasized that continued monitoring is vital to preserve the population.

With wildlife budget cuts ordered by the Legislature still scheduled, Trater said her job as the official "Frog Lady" may be coming to an end. But she is unlikely to stop scanning every inch of water for eyeballs and eggs.

"This population is doing well, so it seems like a good place to cut," she said. "Maybe I'll need to join Frogs Anonymous. I just can't walk by a pond and not count eggs. There is something about the treasure hunt of it. I just love the hunt."

Native Utah amphibians

Utah is home to eight native toads, five frogs and one species of salamander. Here's a list of native Utah amphibians with a note about collecting each. Even in cases where it is allowed to keep them, wildlife officials say it is always better to leave amphibians where they are found to prevent spreading diseases and endangering local populations.

Canyon treefrog (Hyla arenicolor) • Noncontrolled

Columbia spotted frog (Rana luteiventris) • Prohibited

Northern leopard frog (Lithobates pipiens) • Controlled

Pacific treefrog (Pseudacris regilla) • Controlled

Western chorus frog (Pseudacris triseriata) • Noncontrolled

Great Basin spadefoot toad (Spea intermontana) • Noncontrolled

Mexican spadefoot toad (Spea multiplicata) • Noncontrolled

Plains spadefoot toad (Spea bombifrons) • Noncontrolled

Tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) • Noncontrolled

Arizona toad (Bufo microscaphus) • Controlled

Great Plains toad (Bufo cognatus) • Noncontrolled

Red-spotted toad (Bufo punctatus) • Noncontrolled

Western toad (Bufo boreas) • Prohibited

Woodhouse toad (Bufo woodhousii) • Noncontrolled

Relict leopard frog (Lithobates onca) • Prohibited

Visit http://wildlife.utah.gov/rules/R657-53.php for detailed rules on collecting native amphibians in Utah.

Prohibited: no collection without special permit from Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (usually only for research or outreach purposes).

Controlled: need a permit, referred to as a COR (certificate of registration) from DWR. Collection/possession still requires a permit, but for many species its not very difficult to obtain. Cannot "re-release" individuals back in to the wild.

Noncontrolled: Can collect and possess without permit. Cannot "re-release" individuals back into the wild.

Source • Utah Division of Wildlife Resources