This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

If there's anything the Utah Jazz have mastered through the seasons, it is this: They are good at being good.

They are not so good at being great, but they are better at being good, and staying good, than almost any other NBA franchise.

Since 1984, the Jazz have qualified for the playoffs all but four times, which is to say they are 25-for-29 in that pursuit. In two of the nonqualifying years, they were .500 or better. In a league as competitive as the NBA, that's remarkable consistency, especially for a small-market team. And they've done it by perpetually reinventing themselves.

"You don't ever, I mean ever, want to develop a culture of losing in your franchise," says Kevin O'Connor, the Jazz's vice president and general manager. "We always want to win."

The Jazz have never won an NBA title — they swung and missed during two trips to the NBA Finals in 1997 and '98 — but they have successfully maintained their competitive edge, while bridging the gaps between, in three different and distinct periods: The John Stockton-Karl Malone Era, the Deron Williams-Carlos Boozer Era and now the Era of Evolving Promise.

They've greeted each change with shrewd moves and a shrug.

Even during the Stockton-Malone years, a span supposedly earmarked by its steadiness, the Jazz were constantly spinning the spare pieces to keep the invitations to the postseason coming. After the Hall of Famers left, the club was down just a few seasons before it started another resolute playoff climb, with Williams, whom the Jazz moved up in the draft to select, and Boozer, whom they signed as a free agent, and a slew of other new parts.

Compare that with what often happens to NBA franchises when star players leave. They face-plant for years. Even NBA's glamorous teams stumble and bumble. Look at the Boston Celtics after Larry Bird, Kevin McHale and Robert Parish left, or the Chicago Bulls in the aftermath of Michael Jordan. They had clusters of their worst seasons ever.

The Jazz, though, rebounded nicely.

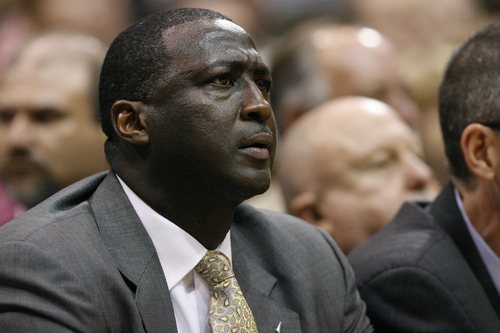

And now, they've done it again, after last season's playoff absence. In fact, the current makeover might be more audacious than anything before. Franchise pillars Larry H. Miller, Jerry Sloan and Williams are all gone, but Greg Miller, O'Connor and Tyrone Corbin have re-imagined the club yet again — this time with a group of young, talented players mixed with a few seasoned veterans.

Nobody expected the Jazz to be a playoff team again so soon. Some experts predicted they would be one of the worst teams in the Western Conference. But here they are, opening the postseason on Sunday against the San Antonio Spurs.

"We started out 27-13 last season," O'Connor says. "And then, we had half a bad season. It went to hell, basically."

Two of the keys in hauling the Jazz back out so quickly were O'Connor's moves to get Al Jefferson essentially out of Boozer's departure (through a trade exception) and trading Deron Williams to New Jersey for Derrick Favors, Devin Harris and two first-round draft picks, one of which turned into Enes Kanter. He saved the franchise the headaches and distractions of dealing with Williams' coming free agency, which was headed in the same direction as Cleveland's ugly situation with LeBron James, Denver's with Carmelo Anthony, New Orleans' with Chris Paul and Orlando's with Dwight Howard.

After Sloan's sudden resignation a year ago, Corbin utilized players like Paul Millsap, Jefferson and Harris, meshing them with youngsters Gordon Hayward, Favors, Alec Burks and Kanter, all of whom are 22 years old or younger.

"If you look at the players we have, they weren't given enough credit," O'Connor says. "Devin has bounced back, Al's played in almost every game, Paul's been a cornerstone and the younger guys have improved. We hope all that continues. I feel good that the guys on this team care about winning."

That's been the team mantra since it relocated to Salt Lake City from New Orleans more than 30 years ago, according to Scott Layden, who once was the team's vice president of basketball operations and now is Corbin's assistant coach.

"The Jazz are a group effort," he says. "They're about doing what's best for the organization. That's trickled down from my dad [Frank Layden] and Larry Miller, and it's kept the team in good shape. Everything is sound and organized, and we're all on a mission for the same thing. There are small egos here. Everybody's in it to help the team win. It's as tight-knit an organization as you'll see in pro sports. That's a big key to the team's success."

There have been failures, too, but the Jazz have kept them to a relative minimum, enabling the club to stay good, always good. And good is good. It's good for business, good for ticket sales and sponsorships, and it's much better than bad.

The question remains whether the team in Salt Lake City will ever blow past good. A couple of years ago, owner Gail Miller was asked about that, and she said: "If you're satisfied with not quite getting there, then you're doing everybody, all your players, a disservice. In reality, that's why you play the game, to get the championship."

Getting that would be … great.

GORDON MONSON hosts the "Gordon Monson Show" weekdays from 2-6 p.m. on 97.5 FM/1280 AM The Zone.