This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Delane Griffin's yard around his Escalante home is filled with a wild potato that his late wife, Leah, transplanted from nearby sites. For decades, some residents in this southern Utah town have enjoyed these tiny potatoes, which have a nutty flavor when prepared properly.

Now, new archaeological research from the University of Utah shows that prehistoric inhabitants of the Escalante Valley could have been nourishing themselves with this tuber for thousands of years, long before potatoes were known to have been domesticated into one of world's most widespread and vital crops.

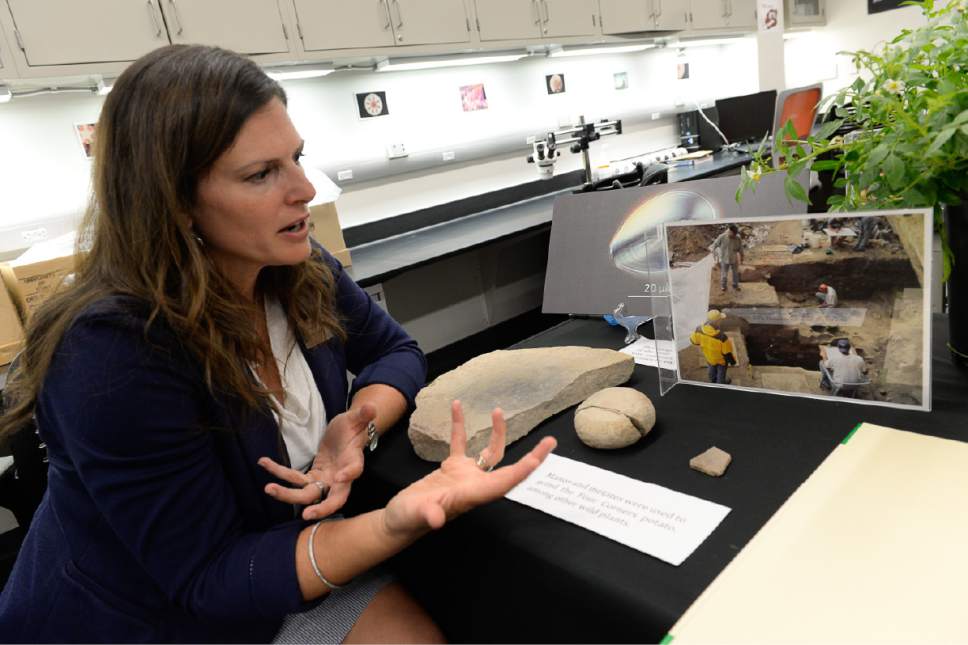

"Our study has found the earliest evidence of potato use in North America," said Lisbeth Louderback, the Natural History Museum of Utah's archaeology curator. "It's about the rediscovery of wild potatoes native to North America and [the plant] being a very important food resource for the past 10,000 years up until today."

She added: "The potato has become a forgotten part of Escalante's history. Our work is to help rediscover this heritage."

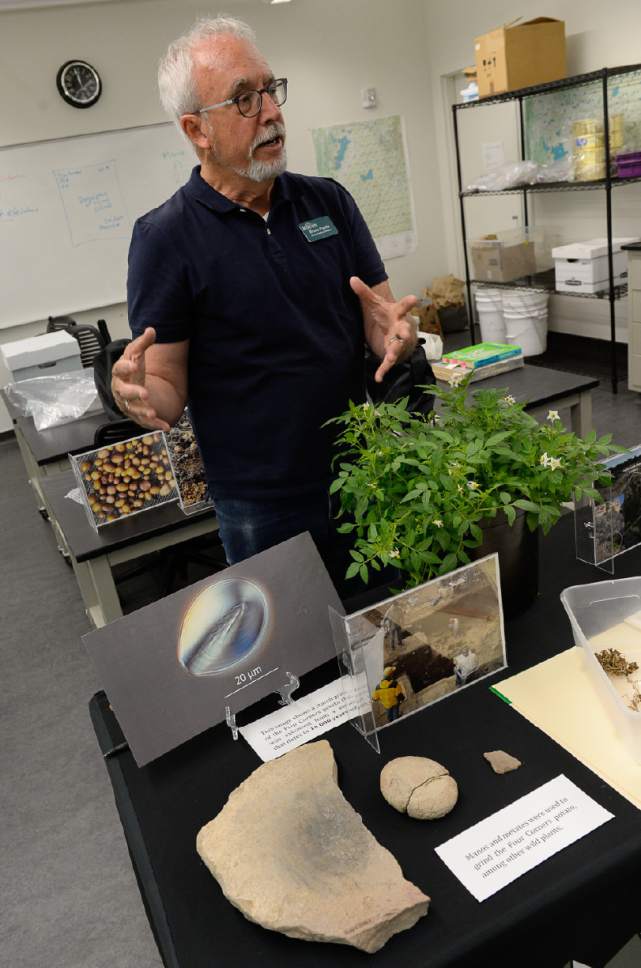

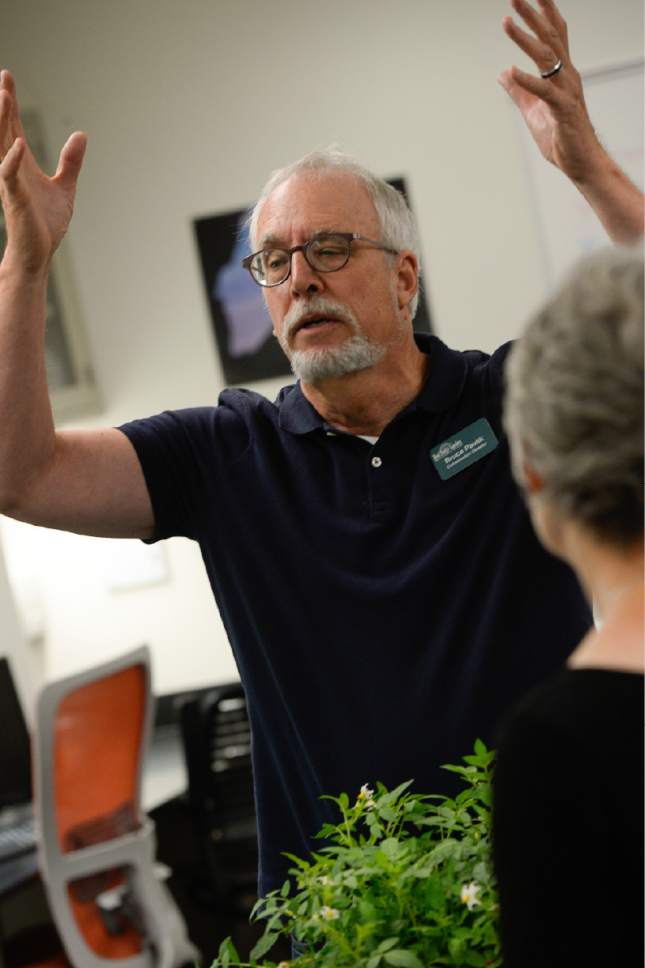

Her findings, based on analyses of plant residues recovered from grinding tools, were posted Monday by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. To develop her hypothesis, Louderback teamed with botanist Bruce Pavlik, conservation director of the U.'s Red Butte Garden, to develop ways to identify potato starch granules and find spots in the Escalante Valley where the Four Corners potato, or Solanum jamesii, grow.

The potatoes the world is now familiar with have all descended from tubers native to South America and bred into thousands of varieties.

S. jamesii, by contrast, is a species native to North America and limited mostly to parts of Arizona and New Mexico. On the Colorado Plateau, it is found in small, isolated populations, according to Pavlik. The tuber is highly nutritious, packing twice the protein, zinc and manganese, and three times the calcium and iron, as the standard Solanum tuberosum.

The Four Corners potato may be relatively tiny, but one plant can yield up to 125 tubers, ranging in size up to a silver dollar.

During the course of the U. research, the scientists discovered these populations are closely associated with archaeological sites. This suggests ancient people brought the potato here and planted them. Genetic analysis backs up this hypothesis, although more evidence must be analyzed, said Pavlik.

Asking today's locals where they could find these plants, U. scientists discovered the trove in Griffin's garden. He is a 94-year-old descendant of Mormon pioneers who settled the valley in 1876. By then, the area already was known as Potato Valley, according to the journals of U.S. Cavalry men who passed through a decade earlier and ate the wild potatoes.

"We have found wild potatoes growing from which the valley takes its name," wrote Capt. James Andrus in 1866.

Griffin's wife was a history buff who was curious why Escalante residents didn't know why the area had been called Potato Valley. Leah Griffin figured the wild potatoes had something to do with it and started growing them.

"It was a rare thing. It wasn't found every place and that was one of the things that made it important to her," Griffin says in a video the U. produced to publicize the research.

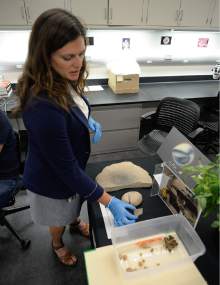

The Griffins' garden was a perfect launching point for Louderback, an assistant professor of anthropology who explores diets of ancient people. Her research interest drew her to the smooth stones ancient people used for grinding plant fibers into something edible.

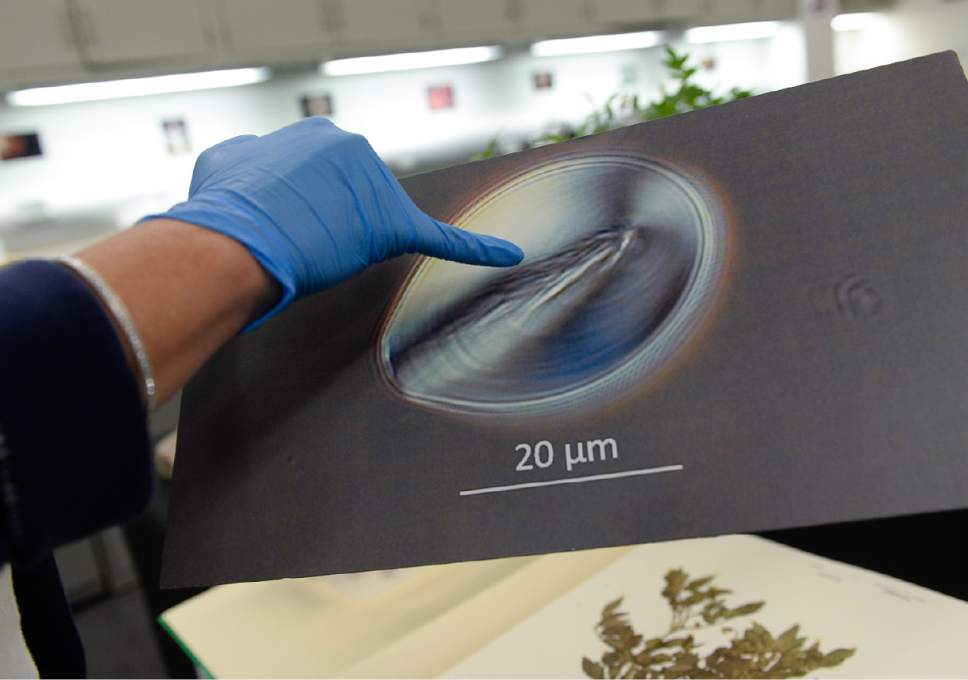

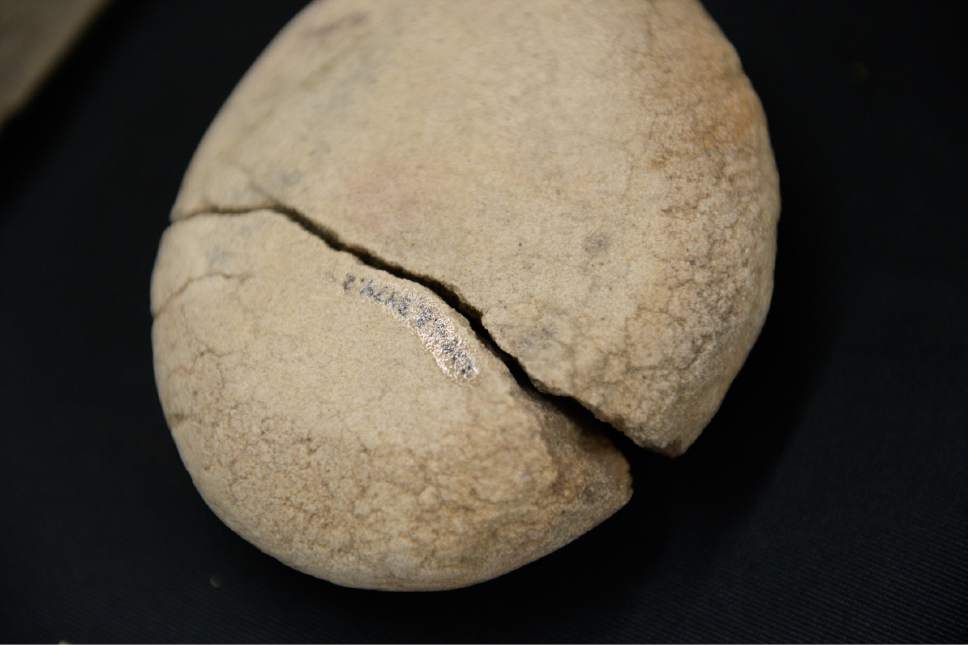

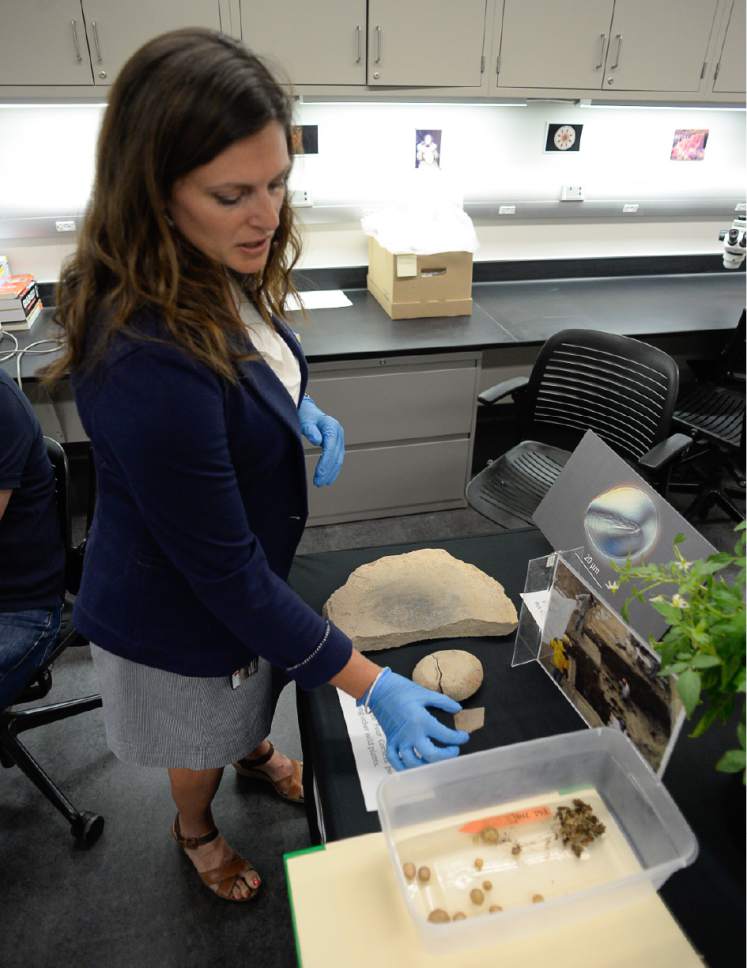

"Grinding plant tissues with manos and metates releases granules that get lodged in the tiny cracks of stone, preserving them for thousands of years. Archaeologists can retrieve them using chemicals, modern microscopy and advanced imaging techniques," she said. "It's a whole other data set that's been untapped all these years because starch grain analysis hasn't been widely used until maybe 10 years ago."

For her doctoral work at the University of Washington, Louderback developed a technique for identifying potato starch grains, which are rare among food plants for having an off-center hila — the point on the granule where the starch layers are deposited. She came up with five criteria for identifying ancient potato starch, then put the methodology to work on the residues found on tools recovered from the oldest archaeological site on the Colorado Plateau.

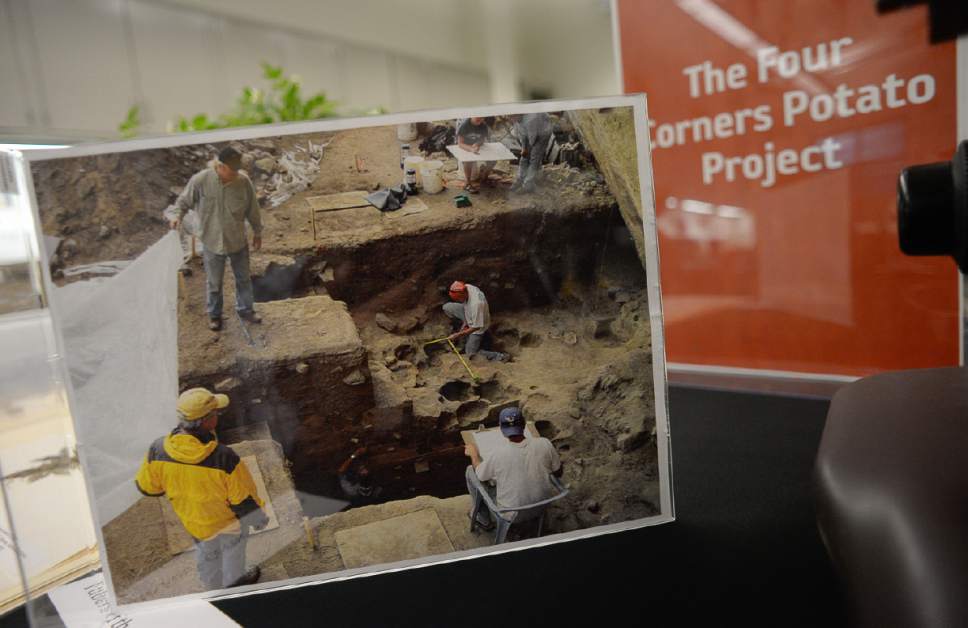

North Creek Shelter is now on property west of Escalante owned by Joette-Marie Rex, who operates the Slot Canyons Inn and North Creek Grill. A decade ago, a team led by Brigham Young University's Joel Janetski excavated the site to find stratigraphic layers indicating continuous habitation dating back 11,000 years. These layers yielded numerous manos and metates that are now housed at the Museum of Peoples and Cultures.

Louderback recovered 323 intact granules from 24 tools in this collection. Nine met all five criteria for the potato and 61 met four, offering proof that the potato was part of the ancients' diet. The oldest tool yielding potato starch dates from 10,900 to 10,100 years ago.

Pavlik explored Rex's land and found the potato growing just a 150 meters from the North Creek Shelter. The team has located four other locations in the valley that harbor small populations of the potato, typically near archaeology. The next nearest known site is 100 miles to the east at Newspaper Rock, a well-known rock art panel in what is now Bears Ears National Monument.

"The fact that it's so unique will help the folks in Escalante want to propagate it. Who wouldn't? This is an important part of why this area was settled, and it deserves to be again," said Rex, who hopes to soon be serving the potato at her bed and breakfast.

Other slow-food and paleo-diet enthusiasts will have to wait. Although Pavlik cultivates the Four Corner potato at Red Butte, he hardly raises enough to sell — but the plant will likely be on display soon at the botanical garden.

—

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. Brian Maffly can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713.

Twitter: @brianmaffly