This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

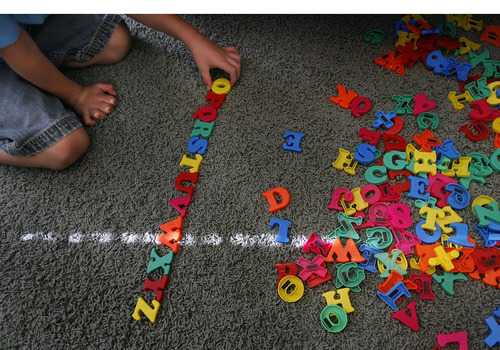

The adorable little boy wearing the backpack is 6 years old, but Logan Hilton can't hold a conversation and doesn't understand how to make friends.

A website designed to raise $12,000 for two years of Applied Behavior Analysis autism treatment for him explains that without help, "Logan would require constant costly care for the rest of his life."

Utah's two-year autism treatment pilot, which launched this year, is intended to help kids like Logan. His mom works for the Department of Corrections, and as the child of a public employee, he can now receive up to $30,000 worth of behavioral treatment each year.

The problem is that families covered by the Public Employees Health Program still need to contribute $6,000 annually to take advantage of the maximum state benefit.

"I'm grateful for it, but at the same time it's not enough," said his mom, Michelle Hilton. "They haven't made it affordable enough."

The Eagle Mountain mom believes more families would have participated if the requirements — paying 20 percent of the cost, and open only to children from age 2 to 6 — had been more flexible.

Only 25 children are signed up for the 50 autism pilot slots in the PEHP portion.

"I think because of that age limit we don't capture all of the autistic kids in our population," said Toan Lam, the PEHP medical director.

When the Legislature passed funding for the autism treatment pilot last spring, it was heralded as Utah's solution to the community's simmering demand for state-mandated insurance coverage for autism. The pilot provides a limited number of slots to children covered by PEHP and Medicaid. Additional state funding and private donations are expected to create openings for other children.

Supporters say any funding is better than none, because Utah does not require insurers to cover autism treatment.

But frustrations have already arisen from parents, as the program's limitations emerge and $1 million in private donations remains elusive.

Rep. Ronda Menlove, R-Garland, who sponsored the bill to create the pilot, said the money is still in the pipeline. The problem, she said, was bureaucratic, and an Aug. 15 press conference will reveal the donations.

"The entities that are contributing are waiting for the autism treatment fund to put the rules in place," she said.

Without the money, the state would be able to fund only 30 autistic children in that portion of the pilot. The private donations would expand the benefits to several dozen more.

The Medicaid portion of the pilot is set to launch this fall and will serve slightly more than 200 children. Enrollment has not yet begun, but families can sign up for electronic updates.

"We're anticipating that we'll have more people apply than we have openings," said Michael Hales, the state Medicaid director.

Children will be chosen at random — not based on their level of autism — though slots will be distributed statewide.

The children who are selected will have their progress measured over time to see whether the treatment is effective.

For now, the family's plan is for Logan to start attending a treatment center in Draper full-time this fall. His mom agrees that contributing $6,000 a year toward his treatment is far better than the more than $20,000 many families pay out of pocket for their children.

But if she had understood the actual cost, she might have made different choices.

"Had I known I probably wouldn't have applied, either," Hilton said. "We just don't have that kind of money."

Want to help Logan?

O Visit his website and his family's effort to get him treatment at http://loganstreatmentfund.com/