This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

It's not exactly the Schramm Johnson Tea Room, but hot caffeinated beverages are again being purveyed on the northwest corner of Salt Lake City's Main Street and 100 South.

Two weeks ago, Starbucks opened shop on the ground floor of the 120-year-old Crandall Building in the exact spot where, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Utah "gentiles" huddled in the Tea Room to pass the time and maybe a little scuttlebutt.

Parked just down Main Street from the newly opened City Creek Center, the seven-story gray sandstone masterpiece — named to the National Historic Register in 1977 — will be kitty-corner from the Utah Performing Arts Center, scheduled for a March 2016 opening at 137 S. Main.

If walls could talk the Crandall Building, originally known as the McCornick Building, would have a lot to say. It's seen Utah's entrance into the Union, women's suffrage and the Great Depression — even the Olympics. It's seen trolley tracks come and go and come back. It's seen the horse and buggy give way to the Tin Lizzie, the sedan, and, finally, the SUV.

And fashion? Imagine turn-of-the-20th-century customers dropping into the Chalk Garden clothing store, which opened in August, in the second-level space where bank tellers once took deposits. Old vaults now act as dressing rooms.

"We love being here," said Chalk Garden proprietor Deborah Kotter Barkley. "It's a fun place. Tourists come by and say they just want to see it."

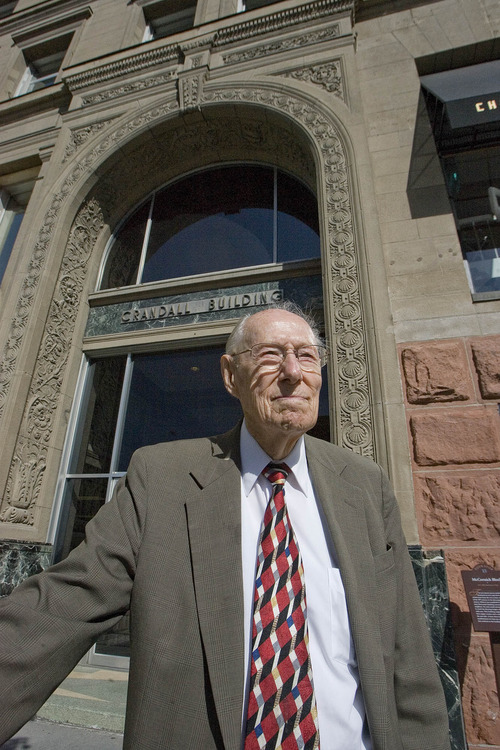

The structure, built by banker and industrialist William Sylvester McCornick, cost $300,000 and was completed in 1892. With its seven stories, it was billed as Salt Lake City's first "skyscraper," recalled David H. Epperson, whose father-in-law, Robert E. Crandall, now owns it.

"It was one of the first buildings in the state with elevators," Epperson said. "They finally decided they could build more than four stories because they didn't have to climb stairs."

Canadian-born and Presbyterian, McCornick saw business potential in Utah before 1890, when the federal government, as part of its war on polygamy, was impeding Mormon business interests. But unlike some non-LDS Utah industrialists of the day, McCornick got along with Mormons, Epperson said. Later, when the LDS regained financial strength, they helped push business McCornick's way.

By 1909, The Salt Lake Tribune declared McCornick & Co. Banking House the largest bank between Denver and San Francisco.

After McCornick's death in 1921, the building was home to several banking interests. In 1955, Crandall and his father, Earl Crandall, bought it from Pacific National Life Insurance. Robert Crandall has owned it ever since and, at 94 years of age, continues to keep regular hours in his sixth-floor office.

"I'll be ready to retire in about 10 years," he said last week.

Salt Lake City's early planning policies encouraged the placement of prominent buildings on corners, explained Kirk Huffaker, executive director of the Utah Heritage Foundation.

"That building still holds great significance from that period,"he said. "It's important to keep the flavor of what things were like 100 years ago."

That flavor was altered a bit in 1909 when it was widened by two window-widths, Epperson explained.

Crandall and Epperson have spent the past 10 years or so bringing the building back to its former glory, including tearing off exterior siding from a 1959 remodel and restoring the red sandstone at street level.

City Creek and the Performing Arts Center will help bring a new era downtown, Epperson said, and the Crandall Building will be part of it. "With Chalk Garden and Starbucks, we've gotten the corner back to its original appeal and vitality."