This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Like most people in 1984 who saw the first installment of "A Nightmare on Elm Street" in theaters, Angela Smith was a teenager. Like most people, the film scared her out of her wits.

But unlike most people, the Wes Craven film had the added effect of guiding her scholarly career.

"What stuck in my mind was the backstory of Freddy Krueger being burned by angry parents because he murdered children," Smith said. "I've always been interested in what produces the monster."

And why monsters produce such willing revulsion in audiences. One master's degree and a doctoral degree late, Smith, an associate professor of English and gender studies at the University of Utah, concluded that people react to horror films most viscerally when they also fear harm to their own body.

In many horror films, especially the iconic titles of the 1930s, that harm is often represented as a deformity or disability inherent in the creature that repulses us. Director James Whale's monster in the 1931 film "Frankenstein" sports a flat head, moaning and shuffling his way toward victims. Bela Lugosi's Dracula works on the unease many Americans felt toward "tainted" foreign blood, and alien East European immigrants. Most telling of all, Tod Browning's 1932 film "Freaks" called into question the dread people felt toward the "unfit" after the eugenics campaign to cleanse the population of people deemed deformed and unhealthy had captured the public discourse.

Most prior discussion of horror in literary studies treated the monster as a symbol or representation of Freudian concepts such as the id. What seemed obvious to Smith was that the primary mechanism used by horror to elicit audience reaction was right in front of our eyes: There was something different about the way they looked.

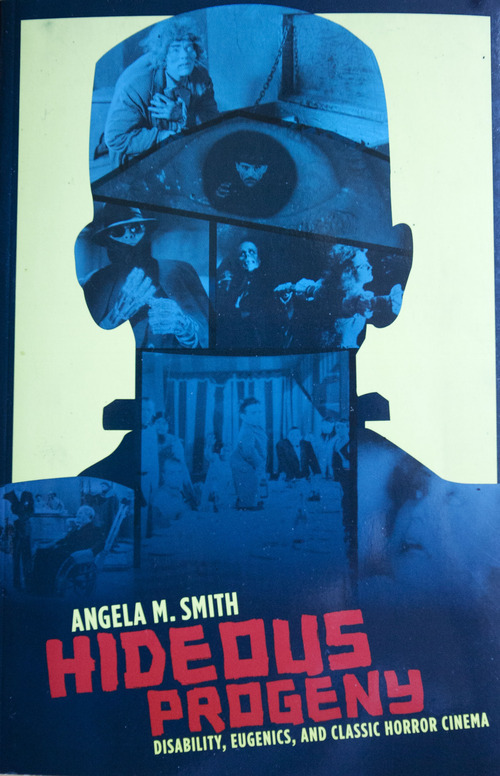

Smith developed the argument in her first book, Hideous Progeny: Disability, Eugenics, and Classic Horror Cinema, published this year by Columbia University Press. "Horror is the only genre named for the effect it tries to elicit from viewers," Smith said. "They're as honest as films can get, in a way. When the rest of society is trying to tell us that we can be perfect, or in complete control of our health, these films remind us how vulnerable and changeable our bodies are. It's a fear everyone lives with, but we deny it as strongly as we can."

Hackles of "politically correct" often arise when English professors invoke a field of study few have ever heard of. Smith said one point of "disability studies" relevant to horror films is that the field reminds us that we all become deformed, disabled, or both, if we live long enough. The shock and discomfort that horror films provoke, then, is quite real. Hence, their undeniable power.

That unease lends itself to interesting parallels in ways that society attempts to control the image of the human body, whether through eugenics, or the way disabled people are treated or viewed in an "ableist" culture.

Michael Bérubé, a literature professor at Pennsylvania State University where he directs its Institute for the Arts and Humanities, called Smith's work, "a terrific book on a fascinating topic that seems, in certain ways, to have been hiding in plain sight."

Smith said she's yet to turn her scholarly attention toward the current zombie craze, but finds it fascinating the way the genre of "the undead" lets the good guys struggling against the zombie horde indulge in such amazing levels of violence. The anything-goes tactics used to combat zombies also erases any moral ambiguity in the struggle against them.

"You almost don't want to be the survivor in the zombie apocalypse because those still alive are having so much sadistic fun," she said. "The zombies are almost symbols for the rest of us, sometime. They just shuffle along the best they can. ... It's always a little more interesting to identify with the monster. They're the ones who don't conform or measure up. Everyone feels like that at one time or another."

Twitter:@Artsalt

Facebook.com/fulton.ben —

'Hideous Progeny'

Author Angela Smith presents her book, at an event that includes a film screening of Tod Browning's "Freaks," as part of the Utah Humanities Council's Fifteenth Annual Book Festival.

When • Tuesday, Oct. 16, 7 p.m.

Where • Salt Lake Main Library Auditorium, 210 E. 400 South, Salt Lake City.

Info • Free. Call 801-359-9670, 801-524-8200 or visit http://www.utahhumanities.org for more information.