This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Eunice, N.M. • Local leaders here are polishing their pitch to attract a type of business most places would shun: storing the nation's high-level nuclear waste.

They've already teamed up with an international nuclear company to get an edge on any competition. They've bought land and built a Web page. They've even met with the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

"We're pushing it real hard," said Eunice Mayor Matt White, whose small community envisions a national nuclear megamall.

This is exactly the sort of inspiration that President Barack Obama's Blue Ribbon Commission on America's Nuclear Future was hoping for last January, when it suggested a new, nationwide search for communities interested in hosting nuclear waste. With the demise of the Yucca Mountain repository in Nevada, the U.S. Energy Department needs to redouble its efforts to find a permanent disposal site for about 71,000 tons of spent reactor fuel.

And, until that's a reality, the commission suggests a search for a place to consolidate waste now scattered at reactor sites around the country and to store it "temporarily" — such as the site proposed by Private Fuel Storage and the Skull Valley Band of Goshute Indians in Utah.

An Air Force retiree who used to pilot F-16s over the Utah Test and Training Range near Skull Valley, White said his community in New Mexico formed the "Eddy-Lea Energy Alliance" and joined the French global nuclear company Areva last fall in unveiling its storage-site bid. The plan would repurpose 1,000 acres bought for a different atomic energy project to build a storage pad for the ever-growing volume of reactor waste.

The mayor describes the storage site as the next logical step in the diversification of a local economy that spent decades suffering the rise and fall of the oil and gas industry.

"It is more dangerous to work out there in that oil field than this plant will ever be," said the mayor, who met with reporters recently in the conference room of the new Urenco uranium-enrichment plant that his community invited to the area a few years ago.

—

Nuclear megamall • The growing nuclear complex includes the $3 billion enrichment plant, the federal nuclear-waste repository at the Waste Isolation Pilot Project in Carlsbad and the new Waste Control Specialists' low-level radioactive waste site just over the New Mexico-Texas border, across the highway from the enrichment plant. In addition, federal regulators have just approved a depleted uranium de-conversion plant nearby.

White credits the facilities with a local unemployment rate of 5 percent when the national economy was tanking. There are new businesses: a restaurant, a bank, a drugstore, a dollar store and proposals for a flower shop and apartments, said White, whose town has 3,000 residents.

And Urenco has established a foundation that distributes $50,000 a year among community programs, like the Girl Scouts, the Boy Scouts, a teen pregnancy program and school science and math initiatives. Plus, 20 students have received "free-ride" scholarships for the nuclear technical training at New Mexico Junior College.

"They have definitely lived up to what they said they would do," said Ella Jackson, president of the nearby Hobbs NAACP.

She recalled how she was a little suspicious of uranium before Urenco sent her and other local leaders to their separation plant in Almelo, the Netherlands. She spent an afternoon talking with a neighbor of the plant, taking note of the flowers in the garden, the birds in the trees.

"By the time I left," said Jackson, a nurse and grandmother of three, "I was convinced it was safe."

The president's Blue Ribbon Commission, co-led by Utah native Brent Scowcroft, had visited the Eddy County community of Carlsbad before issuing its eight recommendations for dealing with the nation's nuclear waste backlog. In contrast, the January report, cited Utah's experience with the PFS-Skull Valley Band of Goshutes plan as an example of how not to handle nuclear-waste projects.

—

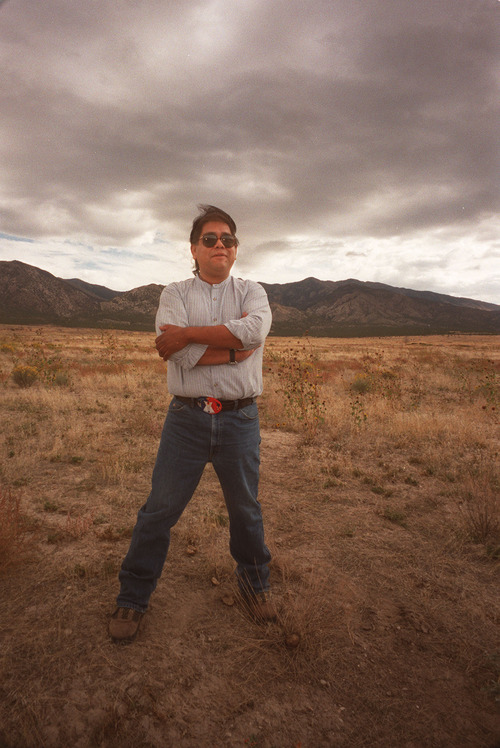

Skull Valley • The 100-member Skull Valley Band saw nuclear storage as an opportunity to bring sorely needed economic development to the isolated community. And the nuclear-company consortium behind it saw a way to move reactor waste off the grounds of more than 60 power plant sites.

But Utah leaders, including three governors and the state's congressional delegation, spearheaded the successful fight to derail the project, which is still under review by the Interior Department. The Utah public strongly opposed it, according to polls.

Federal regulators approved the $3 billion Skull Valley project in 2006 after 10 years of licensing review, but the Interior Department blocked further development through a couple of administrative rulings that were later overturned by the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Blue Ribbon Commission put "a new, consent-based approach to siting future nuclear waste management facilities" at the top of its recommendations list.

"In practical terms, this means encouraging communities to volunteer to be considered to host a new nuclear waste management facility while also allowing for the waste management organization to approach communities that it believes can meet the siting requirements," Scowcroft and co-chairman Lee Hamilton told a Senate committee this fall.

—

Lingering interest • Whether Utah might still be in the running for a new site is unclear at this point.

But the legal wrangling about the Skull Valley site isn't over. And Skull Valley Chairwoman Lori Bear says discussions are ongoing with the Interior Department. Asked if the Skull Valley Band might revive the project if Congress sought proposals, she said: "The Band will review and consider all options if and when federal legislation is enacted."

Other communities might be interested, too. San Juan County leaders advanced a proposal around 20 years ago as part of the same government incentive program the Skull Valley Band used. Then-Gov.-elect Mike Leavitt lumped it together with the Goshute idea and declared, "over my dead body."

Former San Juan County Commissioner Lynn Stevens said he still thinks it would be a good idea to use state school trust lands for that sort of economy-boosting enterprise.

"The possibility would certainly be worth a discussion," he said, noting the area's history of uranium mining and milling. "I think it has more than a 50-50 likelihood of being well received."

But Matt Pacenza, policy director for the Healthy Environment Alliance of Utah, said his group sees high-level waste storage as a safety issue, whether it's being moved around or possibly stranded forever in what was intended as a short-term answer to high-level waste. "It's just not a long-term solution," he said.

Meanwhile, Ally Isom, deputy chief of staff for Gov. Gary Herbert, said the Governor's Office was unaware of any Utah community besides the Skull Valley Goshutes that has publicly expressed interest in hosting a storage site.

"Governor Herbert is unquestionably committed to ensuring the safety and welfare of Utahns," she said in a statement. "So, he believes a state should not only have input in any siting process but [also] that the governor of a host state must have a decision-making role, regardless of whether the proposed location is on public, private, or tribal lands."

Twitter: @judyfutah