This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

It isn't seeing her tribe's name or sacred symbols on underwear that hurts Monique Thacker the most. It isn't the occasional images of Utah Ute fans in headdresses partying in makeshift tepees that grate on Cameron Cuch.

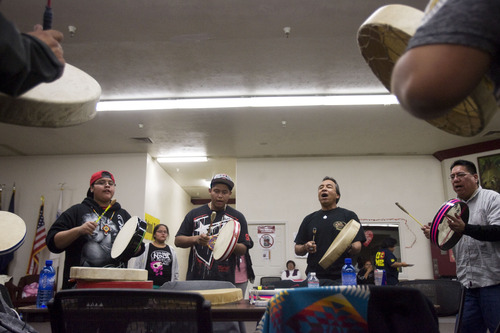

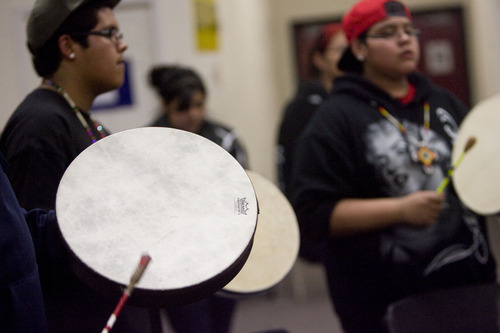

It isn't even the beating of drums, the Utes' sacred symbol of Mother Earth, during University of Utah sporting events that stings tribal Utes.

As insensitive as these portrayals of their culture seem, they're not what cause the most damage.

Most damaging, they say, is their belief that the U. embraces their sacred symbols but not them.

More and more, Utes such as Thacker and Cuch say their tribal name and the drum and feather emblazoned on U. athletic apparel symbolize an uncomfortable compromise their tribe believes it made to gain mainstream exposure it hoped would help keep their flagging culture relevant.

The U., they say, isn't keeping its part of the deal.

The school has a "moral obligation" to do more, Cuch said. "They profit off our name, but we don't see much in return."

—

Uneasy compromise • The Utes' growing frustration stems from the most recent in a series of agreements the tribe has negotiated with the U. over use of its name and symbols.

Reached in 2005, the agreement came after the NCAA identified Utah as one of 18 colleges that still used American Indian names and symbols.

In an effort to avoid NCAA restrictions or a logo change, the school sought approval from the Utes for continued use of the symbols. The tribe endorsed the team name and drum-and-feather logo, and the U. received NCAA approval to proceed.

Why the tribe offered its endorsement remains a point of contention, however. Utes such as Cuch maintain the tribe granted permission with the understanding Ute students would receive scholarships and other opportunities in exchange for use of the name and logo.

"We were told they talked to alumni and were putting together a fund," Cuch said. "We've been disappointed. We should have the support of the college for our culture and language. That was one of the business deals."

Utes growing up on reservations in northeastern Utah need the scholarship opportunities the U. could provide, said A.J. Kanip, director of operations for Ute Tribal Enterprises in Fort Duchesne.

Of an estimated 300 American Indian students at the U., only a handful are Utes.

"It would be a goal for the native community that once they complete high school, there are a lot of options through the tribe," Kanip said.

Utes want to be singled out among other minority student groups as a culture deserving of being the school's namesake, according to Kanip and Cuch.

"We want to build meaningful relationships," Cuch said. "We want the leaders to know who these students are."

In addition, the tribe seeks more involvement on campus, said Renia Willie, a Ute Tribal Enterprises accountant.

If the Utes are going to be the Utes, she said, then really be the Utes.

"I remember when there would be cultural dances there before events," Willie said. "Now we aren't invited to anything. They should come out to powwows and get to know us and what the symbols really mean, and we should go there and have opportunities for dances and things like that and take kids to the football games."

The school welcomes continued interaction and discussion with the tribe, U. Vice President Fred Esplin said, but emphasizes the agreement was never a commercial one.

"It's our view in the administration we will only use the Ute name with permission from the tribe," he said. "If that permission is withdrawn, we would cease using it. It was never meant as a financial transaction. That isn't what we wish it to be."

The U. sets out to help Utes and all American Indians, he said.

The College of Engineering is training tribal members in oil and gas technologies.

Esplin also pointed to a housing project the U. is involved in with the town of Bluff on the Navajo reservation and said the language department has been proactive in preserving American Indian languages.

"We welcome all Native Americans and want students from all tribes to come to the U."

—

Not just a Ute issue • The controversy runs deeper than questioning whether the U. should do more for the Utes. Some ask whether the school should continue to use the drum-and-feather symbol at all.

The drum and feather are sacred to many tribes, not just the Utes. To see them flaunted is an aberration to many who say the Utes have no right to give universal permission for their use.

The drum symbolizes the heartbeat of Mother Earth and its people. Feathers, particularly eagle feathers, are valued as pathways for the wearers to express themselves to the creator. The white and dark parts of the eagle feather are said to represent daylight and darkness and summer and winter. Birds carry the messages between Earth and the spirits above.

Misuse of the drum and feather is an issue for all American Indians, said Matthew Makomenaw, a member of the Odawa tribe and director of the American Indian Resource Center at the U. of U.

"You can't control images and names and how it impacts the climates on campus," he said. "We want to help the climate."

Still, others say sensitivities can be overblown.

"Everyone is entitled to their opinion, but I don't see that having the symbols on a coffee mug or lanyard around someone's neck is something I take issue with," said Sage Cesspooch, a Ute who earned a sociology degree at the U. in the 1990s. "So much has been commercialized. Look at Cinco de Mayo and Corona beer or how much money Guinness makes on St. Patrick's Day and those are days of honor, too."

—

Beginning of the end? • As outside pressure from the NCAA and other groups has grown for schools to abandon American Indian symbols, the Utes are gradually phasing out the drum-and-feather logo.

In late 2008, the U. of U. said the logo would no longer be used on items or buildings deemed as permanent, or those lasting for more than a year, and it would be referred to officially as the "circle and feather."

The logo remains on uniforms, apparel, media guides and promotional bits, but more often, the less inflammatory "Block U" stands as the symbol for the Utes.

U. Athletic Director Chris Hill said the decision was made to go with the "Block U" on a national level because it is the universal symbol of the university.

"We hope to reinforce that our entire university is a member of the Pac-12 Conference," he said, "not just our athletic teams."

Meanwhile, Hill said, the school has met with tribal representatives to address concerns about inappropriate use of symbols. Those meetings resulted in a 90-second video posted on YouTube and social media cautioning fans to be more respectful in using symbols.

Administrators also met with coaches, staff and student athletes regarding proper use of symbols on uniforms and in marketing materials.

Football coach Kyle Whittingham said he felt it was important his team know of the Utes' culture and tries to have a tribal representative speak to his team every year. Utah's football media guide also includes an explanation of "What is a Ute," and Hill said the staff and athletes are educated on the Utes.

Such information hasn't yet made it to all U. athletes, though.

Jason Washburn, a senior on the men's basketball team, said he has pieced together the story of the Utes but acknowledged he knows little of the culture or of the symbols' significance.

"There is a lot of pride in the name and in the drum and feather, and if there is that much pride, then we should be willing to take 10 minutes, and whoever wants to teach us, let us learn it," he said. "It would benefit us in a lot of ways."

—

Marketing boon • Even as it phases out the drum-and-feather logo, the U. remains in a minority of schools that maintain American Indian names and symbols.

Of the 18 schools the NCAA identified in 2005 as possibly subject to bans for their use of logos and mascots, 14 removed all references to American Indians.

What would happen if the Utes changed their identity?

While some administrators believe some fans would protest — citing the outcry a few years ago when the school decided to use the "Block U" in favor of the drum and feather — others say there is no better time to make a change.

"If it is done right and if you have a new name and new colors, I think there would be a surge in people buying new merchandise," said B. David Ridpath, a professor of sports administration at Ohio University. "There is a newness to it and, if it is marketed right, they could make a lot of money."

Today's climate almost encourages schools to have a variety of uniforms and color schemes, said Tony Weaver, assistant professor for sport and event management for Elon University in North Carolina.

"It's almost a time when we expect schools to change uniforms," he said. "We have this Oregon effect where it seems like every weekend there is a new helmet or team. Maybe now would be a good time to introduce a new brand and logo and move away from the sensitive topic. It could be good for everyone."

It wouldn't be easy, however,

Esplin sees "a very strong sentiment among many of our fans and alumni that these are important athletic traditions."

Fan Scott Monson said the U. wouldn't be the same to him without its ties to the Utes.

"A Block U and the red-tail hawk just don't have the universal recognition that comes with the drum and feather," he said. "If the Ute tribe were not supportive, I would feel differently."

Twitter: @lwodraska —

Use of Native American names and imagery at the U. of U.

1950s • Utah, which used "Utes" and "Redskins" interchangeably from its earliest days, also starts using a boy named "Hoyo" as its mascot.

1972 • The dual team name is dropped in favor of the "Utes."

1975 • Utah begins using the drum-and-feather logo

1980s-90s • The Utes adopt the "Crimson Warrior" as a mascot. The horseman rode onto the field before football games and speared a hay bale.

1996 • The Utes adopt a red-tailed hawk as the new mascot.

2005 • The NCAA subjects Utah and 17 other schools to restrictions for using Native names, mascots or images. The Utes win an appeal after the Utes agree to the school's continued use of images.

November 2008 • U. Athletic Director Chris Hill acknowledges the school has started to phase out use of the drum-and-feather logo on all items deemed as permanent. The school also starts referring to the "drum and feather" as the "circle and feather."

December 2008 • Fourteen students protest on the U. campus with shouts of "we want scholarships" and "pay the bill, Chris Hill." Dissatisfaction with the university's decision to give up $2.1 million in federal grants for teacher training for American Indian students sparks the protest. The U. said it didn't have $1.5 million in matching funds for 10 students as required. Instead, it hired a director of American Indian teacher education.

2012 • The U. announces on Jan. 5 it will retain the Utes name and the circle-and-feather logo. The decision follows discussion with students, administrators and tribal representatives."We have to be careful and sensitive," Hill said, "to both the American Indian tribes and our fans." —

Use of American Indian names and imagery nationwide

1968 • The National Congress of American Indians launches a campaign to address stereotypes in films and on TV.

1970 • The University of Oklahoma retires its Little Red mascot. Protests against the Cleveland Indians baseball team's name intensify.

1972 • A student petition leads Stanford University to discontinue use of Indian names and logos. Pressed by Seminole leaders, Florida State retires the use of "Sammy Seminole," and "Chief Fullabull."

1979 • Syracuse University retires its mascot "the Saltine Warrior."

1992 • Five American Indians petition to remove the trademark status of the Washington Redskins team name to prevent sale of branded merchandise without royalty payments. The D.C. Court of Appeals in 2005 rules there was insufficient evidence to support the removal. The U.S. Supreme Court refuses to hear an appeal.

1994 • St. John's University changes its nickname from the Redmen to the Red Storm.

1994 • Wisconsin urges all state schools to discontinue use of names and logos.

1999 • Three Utahns who claimed to be Washington Redskins fans received vanity license plates that read "REDSKIN," "REDSKNS" and "RDSKIN." American Indians challenge the plates' issuance under a code forbidding the use of vulgar or derogatory terms. The Utah Supreme Court reverses the Utah Tax Commission's ruling that the term "redskin" was not offensive and the vanity plates are revoked.

2001 • The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights calls for use of American Indian imagery and names by non-native schools to end

2005 • The American Psychological Association issues a resolution that declares the "use of American Indian mascots, symbols, images and personalities undermines the educational experiences of members of all communities — especially those who have had little or no contact with indigenous peoples."

2005 • Utah is among 18 schools the NCAA vows to restrict for using American Indian names and symbols.

2007 • William & Mary is allowed to keep "The Tribe" nickname but eliminates the use of feathers in its logo.

2007 • The University of Illinois, under pressure, retires use of Chief Illiniwek as a symbol.

2010 • Wisconsin passes the nation's first law regulating the use of American Indian names in public schools.

2012 • Oregon bans the use of native symbols and names in public schools. An estimated 15 schools affected by the ban have until 2017 to comply.