This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Carolyn Tuft starts her morning with a pain pill.

She takes more throughout the day to take the edge off her constant companion: Suffering from a shotgun blast that tore away flesh, nerves and muscles in three places, and the lead poisoning from the buckshot still in her body that leaves her bones throbbing.

"I wouldn't be able to get out of bed or function without it," said Tuft, 50, a victim of the 2007 Trolley Square shootings, where her daughter and four others died.

Roy Bosley lives with a different kind of pain: Memories of arriving at his Ogden home to find his wife of 38 years, Carol, dead from an overdose of the pills she took for back pain.

It was the day before Thanksgiving, Nov. 25, 2009.

"I had been running around the valley looking for bread crumbs for the stuffing she was going to make. The holidays were her big thing," said Bosley, now 65. "It was horrible. My whole world came to an end right there."

If Carol Bosley and Carolyn Tuft illustrate polar ends of an ongoing debate over the safety and effectiveness of opioids, their former doctor, Lynn Webster, is among the physicians whose aggressive prescribing triggered it.

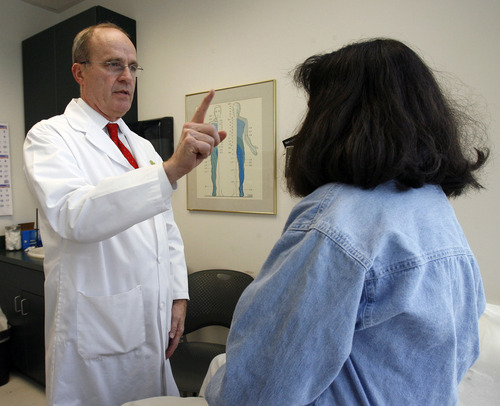

The Utah anesthesiologist has spent the past decade writing and lecturing about how to safely prescribe opioids, as use of the drugs exploded in the U.S. He created a widely used screening tool to identify patients at risk for abusing them. Last week, he spoke to a federal panel about proposed limits on medications containing hydrocodone that he fears might hurt patients like Tuft.

But the 62-year-old is also under federal scrutiny. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration is investigating overdose deaths of patients of his former pain clinic. And a U.S. Senate Committee on Finance is examining payments he's received from opioid manufacturers as president-elect of the industry-backed American Academy of Pain Medicine.

"There's no area of medicine that's more challenging today. [As a pain doctor] you're damned if you do, and you're damned if you don't," said Webster, downplaying the investigations. "Everything I have done over the last decade has been about trying to help patients and ensure safety in our field."

Webster was recently quoted in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel acknowledging that many as 20 of his former clinic's patients died of opioid overdoses — which, he said, "has driven me to push for safer prescribing."

On Wednesday he denied saying that.

"Like most practices we had patients who died. There were people who died from cancer, heart and lung disease and people who committed suicide and used their medications to overdose. It's always a tragedy when that occurs," he said. "All of their care was as good as it could be at the time. If anyone had an adverse outcome we all shared in that tragedy."

—

Who benefits? • One expert says the safety precautions Webster promotes — flagging patients at risk for abuse, frequent office visits and urine drug screens — make sense, but haven't been proven to stop addiction.

"The problem is, in real life practice these things don't get done consistently and we don't really know if these precautions work," said Michael Von Korff, an epidemiologist in Seattle and a member of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing.

The academy and other physician groups "understated the risks and overstated the benefits" of narcotic pain killers, fueling a dramatic rise in opioid prescriptions and overdose deaths, said Korff.

But there's no evidence these drugs are effective at managing chronic pain and medical opinion is changing, he said. "These are treatments that should be used selectively, with great caution and at low doses."

Indeed, Webster concedes, "opioids are not the best treatment for many people." There aren't enough long-term studies to show what subset of the population benefits, he said.

But currently, he said, there's no substitute for the "many people who simply could not live unless they had strong pain relievers."

Tuft, his former patient, is one of those people. "I live on pain medication," she said, noting she shares Webster's concerns that new restrictions could make the drugs more expensive and difficult to obtain. "I hate that I have to live like that, but it's just a fact of my life right now."

Patients need to be warned of the dangers, Tuft said. "But if I take too much, more than prescribed, that's my fault, not the doctor's."

—

The rise of Lifetree. • Webster started Lifetree pain clinic in South Salt Lake in the 1990s. For nearly two decades he and a crew of nurses and other mid-level providers treated thousands of high-risk patients for chronic pain.

He remains licensed and has not been disciplined by the state's Division of Occupational and Professional Licensing.

But he no longer treats patients, having sold the clinic in 2010 to focus on industry-funded research — months after a visit from the DEA.

"They came in and asked for records. I don't know if it was a raid. From what I understand it's relatively routine for the DEA to request records from time to time," said Webster.

The DEA visited Webster again last fall, inspecting the Lifetree Clinical Research facility he co-founded in 2003 in the same building as the clinic. Lifetree, which merged with CRI Worldwide in 2010, is hired by drug makers to test new therapies on patients, including drugs for pain.

The Senate committee asked manufacturers about their payments to Webster during a probe that began last year of financial relationships between the companies and groups that advocate opioid use, such as the academy Webster helps lead.

"The Senate never contacted me," Webster said. "They're not investigating me. They're investigating the influence the industry may have over the prescribing of opioids."

Webster said the money funded research. "None of it went to me. I oversee the clinical research but I'm salaried by Lifetree."

Drug makers pay him smaller amounts for consulting and lecturing, he said, adding, "Most lectures I've been involved in have been educational, not advocating for any pharmaceutical product."

He admits, however, having no control over which of his trials gets published. "We've published negative trials, but I think all of them should be published, not just the findings, but the raw data. We need to be more transparent," he said.

—

'Bottom line, she was addicted.' • The DEA and U.S. Attorney's Office in Salt Lake City would not comment on their active investigation of Webster. But Roy Bosley said he was interviewed last month by local and federal authorities.

"They indicated there was an ongoing investigation and said they would get back to me and would I be willing to testify. I said I would." He added: "I just hope to stop someone from experiencing what I went through."

Bosley sued Webster and two of his advanced practice nurses for malpractice in April 2011, settling for an undisclosed amount. "I'm trying hard to move on, not away from my wife and her memory, but to reestablish my life," he said.

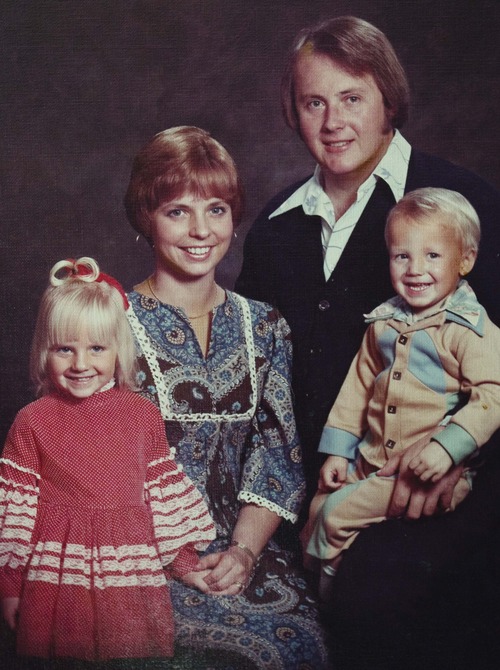

Carol, Bosley's wife, was thrown through a car's windshield in an accident in 1992, injuring her back. Despite multiple surgeries, she lived with constant pain, for which she was prescribed narcotics, he said.

In January 2008 she enrolled in Webster's clinic. Over the course of two years, she was prescribed increasing amounts of muscle relaxers, sedatives, antidepressants and painkillers, including oxycodone, Fentanyl and Percocet, court documents said.

Before the accident, Bosley said, his wife was a skilled trauma nurse and attentive mother. On the pain pills she was forgetful, delirious, incapacitated.

"She would take a pill and forget and take it again. I can't tell you how many times we'd end up in the ER," said Bosley. "I started taking photos of her while she was unconscious, which may sound brutal. But when you're desperate and looking at the love of your life who denies acting this way, you have to do something. She was in denial, but bottom line, she was addicted."

After Carol overdosed in February 2008, an ER doctor had her admitted to a drug treatment program. Weeks later she was "her old self," taking only Tylenol for pain and walking five miles a day, Bosley said.

But by March she was back on pain pills prescribed by Lifetree, he said.

—

The conundrum of pain. • At his wife's urging, Bosley met with Webster. "He told me there was no way my wife was an addict because chronic pain sufferers couldn't be addicted," Bosley recalls.

Bosley said his subsequent calls to the clinic were ignored, even when he complained Carol had used up a 30-day supply of oxycodone in 10 days.

"They said they couldn't talk to us because of [patient privacy laws]," he said. "We made it clear we're not asking for [medical] information, we were asking to give information."

Webster enrolled Carol in a trial of neurontin, an anti-seizure drug shown to alleviate pain, installing a pump in her stomach. And clinic staff continued to increase her painkiller prescriptions.

The clinic never referred her to a psychologist or addiction treatment, the lawsuit alleges. Bosley's lawyer, Eric Nielson, has filed three wrongful death lawsuits against Webster.

"The goal of pain management is to get patients off meds," Nielson said. "The amounts of drugs these patients were prescribed is astonishing. We had one patient who was getting over 40 pills a day...Once Lynn Webster saw a patient for initial intake he never saw the patient again."

Webster denies the allegations, saying he believes Carol committed suicide and declining to elaborate.

Utah data shows people who die from overdoses usually have a history of mental illness, substance or alcohol abuse. They often also have other prescription drugs in their system, including benzodiazepines, for anxiety or insomnia, Webster said. "That's the real conundrum in treating pain."

To illustrate the challenge, he cites a male patient who fatally shot himself after Webster refused to refill his prescriptions.

"I've had patients say anything is better than the hell of pain, the hell of torture," he said. "You're caught. If you don't treat they may commit suicide, and if you do treat and they misuse, they die of an overdose."

Proposed patient protections

A Food and Drug Administration advisory committee has recommended reclassifying opioids that contain hydrocodone from Schedule III to stricter Schedule II restrictions.

Instead of getting a prescription for up to five refills over six months, Schedule II drugs are limited to a 90-day supply in certain cases. And they require up to monthly visits to a health care provider, instead of every six months or once a year.

Hydrocodone is an ingredient in painkillers including Vicodin and Lortab, meant to treat moderate to moderately severe pain. They're used for acute, trauma-related and post-surgical pain, including dental procedures, and frequently for chronic pain.

The FDA has also called for public comment on the science of using opioids for chronic, non-cancer pain, noting that their safety and effectiveness as pain relievers has been called into question. —

Prescription overdoses on the rise

Nationally, drug overdose deaths increased for the 11th consecutive year in 2010, according to data released this month by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

More than half of the deaths involved pharmaceuticals. And prescription painkillers were the leading culprit, implicated in three out of four prescription drug overdose deaths.

Utah already has one of the country's highest drug overdose rates, and the deaths may be creeping back up after large drop.

The number of deaths had declined 28 percent from 2007 to 2010, down to 236 deaths, during a statewide campaign to educate doctors and the public about proper use of pain pills. But the number of deaths rose again in 2011, by 10.