This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Carl Thummel was about $200,000 short.

The University of Utah professor of human genetics had already won the money, about one-third of his lab's annual budget, from the National Institutes of Health. It was due to begin paying out in December — just as the country went off the so-called fiscal cliff.

More than six months later, the money still hadn't come, the victim of federal budget cuts known as sequestration. So he cut his own salary by 25 percent, as well as his technicians' pay.

"They're putting their salaries on the line, and some of them are family breadwinners," he said in July, staring ahead. "That's what we've got to do."

Thummel, who studies diabetes, obesity and metabolism at his 10-person lab, wasn't alone. The U. lost $32 million in research funding in fiscal 2013, dropping from about $393 million to $361 million, due primarily to sequestration. Though Thummel got word this month that his cash would be forthcoming, he said other labs haven't been as lucky. "Each grant for a small lab is essential. In the past years, two grants was not hard to maintain, but it became more difficult and now it's very difficult," he said.

And the effects aren't just academic. The U. is the third-largest employer in the state, and the 2013 cuts alone could cost as many as 640 jobs, many of them off-campus, according to calculations from the U.-based Bureau of Economic and Business Research (BEBR).

"That large of an employer for the state is definitely significant and important for us," said Nic Dunn, spokesman for the Utah Department of Workforce Services. Including its hospital, the U. has more than 20,000 employees.

—

Science slump • While the deep, automatic spending cuts that started in March have been painful for federally funded programs across the spectrum, from the military to Meals on Wheels, university officials say that the cuts to research funding are part of a years-long slump that threatens American innovation.

"It's not just sequestration … there is a steady sense of disinvestment from science exploration, investigation and research," said Dean Li, the vice dean for research and chief scientific officer at University of Utah Health Care.

Utah State University, meanwhile, has lost about $25 million of $170 million in promised research funding this year. Jeff Broadbent, associate vice president for research at USU, said less money means fewer new ideas will get funded.

"The sequester is putting a really hard new reality in place for us," he said. "You might not even get in the door with the proposal."

For some, next year will likely be worse. USU's Special Education and Rehabilitation Department hasn't yet lost money to the sequester, but at least one entire grant competition next year has been canceled and a teacher-training program for special education students could also be on the chopping block.

"We're dealing with kids that are the most vulnerable kids in schools," said department head Benjamin Lignugaris/Kraft. "It's really a huge step backwards."

—

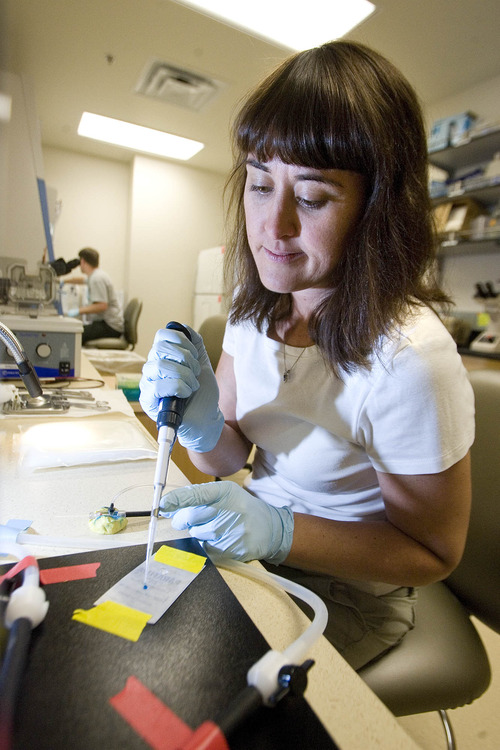

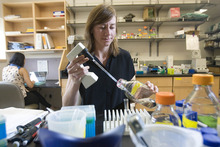

New reality • For young scientists just starting out, the new reality can be harsh. Megan Williams, an assistant professor of neurobiology at the U., is now applying for her first round of grants to get her lab studying brain development off the ground.

The numbers, though, are a bit grim — chances of getting funded, once around 20 percent, are down to 5 percent in some areas, Li said.

"It's just a little bit depressing," Williams said. "I try really hard not to have anything remind me of science before I go to bed."

She expects to hear back on her grant application in the fall. If she doesn't get it, her fledgling lab should be able to carry on for a couple of years with start-up money the university gives all new labs combined with a few private grants she's cobbled together.

"I'll just keep submitting [applications] until I get one," she said.

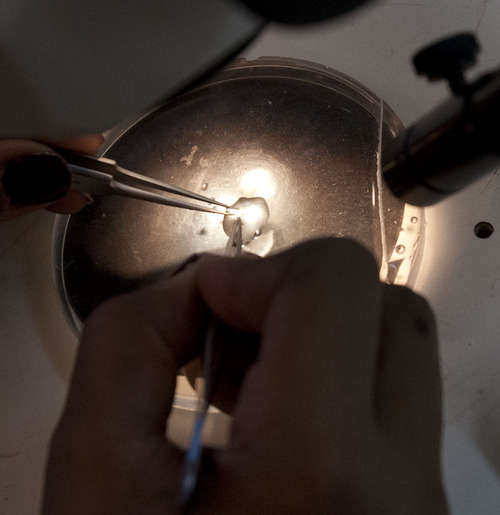

As she spoke, Jennifer Ichida stood over a nearby microscope, studying a sedated mouse with a transparent plate implanted in its head to ensure it was healing properly. The modification will allow the researchers to follow florescent proteins in its brain to determine how it learns.

Ichida, a senior lab specialist, was laid off just before Christmas from the Moran Eye Center, where she studied neural pathways in monkeys for 10 years. The project she was working on was supposed to be funded for five years, but the federal government cut it back to three.

"It's very difficult to get money," she said. "I think good science is still going to happen — I don't think the money crunch is going to stop that— but it's going to make it hard for people starting out or who want to do different things."

—

Job loss • But there could be more job loss. The BEBR calculates that for every $1 million the U. gets in federal research funding, $860,000 is spent in the state, creating about 20 jobs here — six at the university and 14 in the rest of the community.

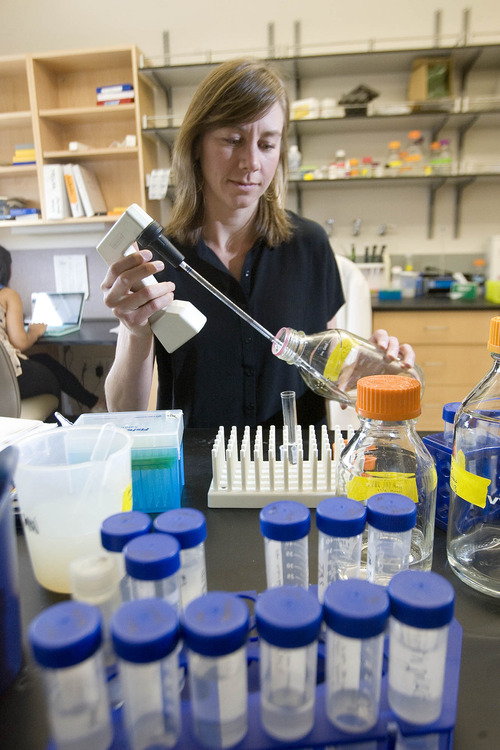

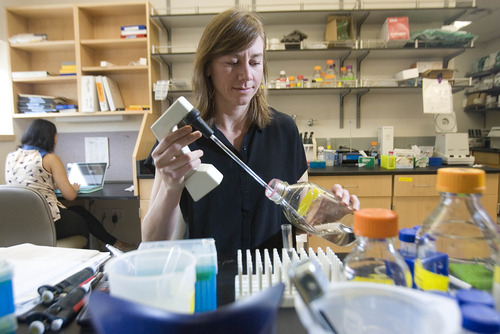

Some of those jobs are at companies that supply the labs. Thummel's lab, for example, spends $20,000 a year on feed and vials for the fruit flies that form the basis of his research. Other jobs are created more indirectly, like when people employed at those companies or at the U. buy clothes, food or housing.

The immediate effect of this year's slump isn't yet clear.

"It's not like [640] people are going to lose their jobs tomorrow," said Jan Stambro, a senior research economist with the BEBR. "I would think it would be a number of years, because contracts at the university typically span more than one year, especially the large ones."

But if the downward slide continues, job loss is inevitable, said Thomas Parks, vice president for research at the U.

"At some point, if the money goes down, people will be let go," he said. Researchers say there's more at risk than today's jobs, pointing to an apparent shift in congressional priorities away from the basic research funding that the government threw its weight behind after the launch of Sputnik in 1957 and redoubled in the war on cancer during the Clinton era.

—

Future of research • The federal government provides the backbone of research funding in America, a model that propelled the country's science and technology achievements and is being emulated by other countries. But while the U.S. expenditure on research and development as a share of economic output has remained constant over the last decade, South Korea has increased its investment by nearly 50 percent, and China has boosted its expenditure by 90 percent, according to Close the Innovation Deficit.

Joined by USU President Stan Albrecht and nearly 200 other college presidents, the effort points to "life-saving vaccines, lasers, MRI, touchscreens, GPS, the internet," as examples of the results of federally funded scientific research, much of which came to the public years after it was funded.

But reinstatement of pre-sequestration funding levels seems unlikely, according to a June report in the scientific journal Nature. The cuts could continue for another nine years, with 8 percent decreases year over year, Joseph Haywood, vice president for science policy with the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology in Washington, D.C., told the publication.

Replacing federal money wholesale with donations or private funding isn't feasible, Li said.

Donations are "helpful, but they pale in comparison to this amount of money every year," he said. And while private companies often build off federally funded research done at universities, it doesn't make sense for them to invest on the basic research level because it's so far from becoming profitable.

But others ask whether universities could tackle federal cuts by becoming more efficient.

"It's not an all-bad thing to have some cutbacks in research," said Richard Vedder, director of the Center for College Affordability and Productivity at Ohio University. Though he decried the "meat-ax" approach of sequestration, he said cuts might "lead us to become more efficient in the way we allocate our research dollars."

Twitter: @lwhitehurst