This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

A sugar rush could be dangerous to more than your waistline, according to a new study from the University of Utah.

Researchers found that male mice fed a diet with 25 percent extra sugar — equivalent to about an additional three cans of soda a day in humans — were less likely to defend their territory and reproduce, while female mice on the same diet died at twice the normal rate. The results are similar to the lab's findings on inbreeding in mice.

"Would you rather be on the American diet ... or have parents be full cousins?" said senior author Wayne Potts, a biology professor. "This data is telling us it's a toss up."

The research was published online Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

Studies indicate that between 13 and 25 percent of Americans get a quarter or more of their calories from added sugars, which also include candy, cookies, fruit drinks and ice cream. While previous studies have found sugar has a toxic effect, they generally used amounts much higher than most people actually eat, said the study's first author, James Ruff.

"I think the big takeaway is the level of sugar we readily eat and think is safe causes major health declines in mice," said Ruff, who recently earned his doctorate at the U. "We're not just talking about some minor metabolic thing. We're taking about increased rates of death and [lower rates] of reproduction."

When Ruff and Potts gave mice the equivalent of about 500 calories of sugar on a 2,000 daily calorie diet for about six months, one interesting result was what didn't happen: The high-sugar mice weren't fatter.

"Our mice would have passed their physical," Ruff said, but "still have negative health impacts."

Another was the differences between genders.

About 35 percent of the high-sugar females died, twice the 17 percent death rate for female control mice. Those who ate more sugar initially had higher birth rates, perhaps due to the extra energy. The rates declined as the study progressed, partly because more of them died.

While the death rate for both male groups was the same — 55 percent, due to the competition for territory — the high-sugar males acquired and held 26 percent fewer territories than control males. They also produced one-quarter fewer offspring, as determined by a genetic analysis.

Mice are a good model for humans because they've been living on a diet similar to the human one for 10,000 years, since the agricultural revolution, Potts said. Up to 80 percent of the things that are toxic to mice are also toxic to humans.

The 156 mice in the U. study got a nutritious chow made of wheat, corn and soybeans with vitamins and minerals.

A glucose and fructose solution, similar to high-fructose corn syrup, was included in the high-sugar chow, based on National Research Council recommendation that people eat no more than 25 percent of their calories from added sugar.

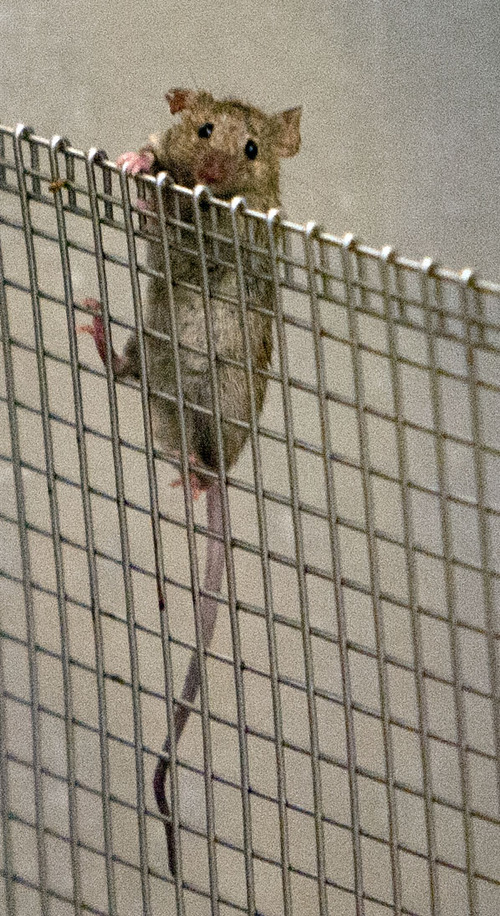

The control mice, meanwhile, got corn starch instead. After 26 weeks, about one-quarter of their lifespan, both groups were released into room-sized pens nicknamed "mouse barns," an environment that allowed them to interact and compete for mates and desirable territories.

Each enclosure was divided into six sections, four of which were considered more desirable territory because the nest boxes were opaque plastic storage bins rather than wire mesh fencing. Once the mice were in the enclosures, they were fed the same diets.

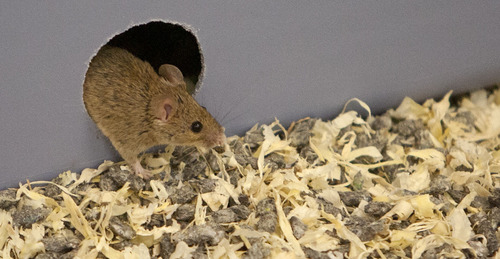

The researchers studied the mice for 32 weeks, watching as they interacted, bred and weaned, a model Potts said is uniquely sensitive to the effects of toxicity because it shows how the substances affect the way the mice live their lives.

"When you look at a mouse in a cage, it's like trying to evaluate the performance of a car by turning it on in a garage," Ruff said. "If it doesn't turn on, you've got a problem. But just because it does turn on, doesn't mean you don't have a problem. To really test it, you take it out on the road."

If the mice stayed on the high-sugar diet past 26 weeks, they might have shown even greater effects, Potts said. Researchers in Potts' immunogenetics lab are working on a method to keep the diets separate after the mice are in the enclosures so they can study the effects of longer-term toxin exposure.

Twitter: @lwhitehurst