This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

For decades, Ron Yengich believed that as a teenager he had wanted to become a Catholic priest.

Now the fiery and driven Utah defense attorney knows that memory was mistaken.

The prospect of the priesthood was his parents' idea, not his, and not as a natural extension of his youthful devotion to the faith but rather as a surefire way to reform him.

"It wasn't me at all; it was them," he says. "I was such a little jerk that they had talked about sending me to the seminary."

Yengich says his father had a nickname for him as boy: "Joe Magarac," and he wasn't referring to the legendary Croatian folk hero known for his strength, bravery and uncanny ability to protect steelworkers. Magarac is a Croatian word for "male donkey," so his dad, Yengich says, was making a point that he was "Joe the jackass."

As a boy, Yengich was often stubborn, hardheaded and difficult. And, yes, as a grown man, he's often been all of those things, too, he concedes.

"I don't revel in that," Yengich says. "I guess there was a day when I did, but I certainly don't anymore. I don't revel in that particular guy."

Which is why, in part, Yengich says his Catholic faith is so important to him. It helps him not be "that particular guy."

"The better part of me, the best part of me, is the guy who translates God's will through me by my beliefs and what I've been taught," he says. "That is fundamentally why I am a believer, because when I get there and when I allow myself [to be] there, then I am a much better person. As a Catholic, I would say I'm doing God's will.

"Now, I don't do it every day," he says. "I fail every day at it. But I also feel very strongly in my religious journey that the mere fact that I fall down does not mean I have to stay there. The religious journey is to get back up again and when I do question it, to think about it and to pursue it."

—

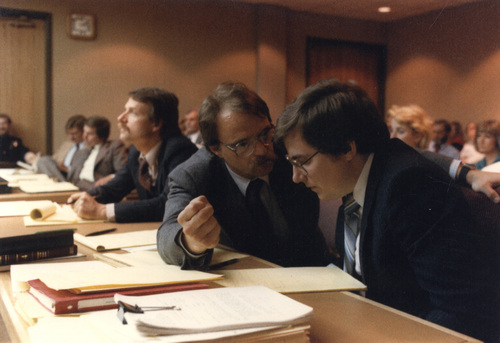

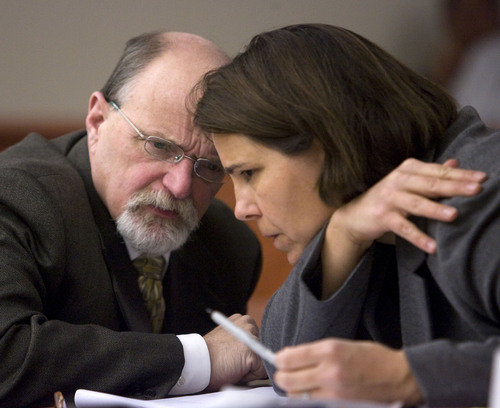

From college to counsel • During his nearly 40 years as an attorney, Yengich has represented the "who's who" and "who's that?" of Utah — from forger and bomber Mark Hofmann, who killed two people, to Reuben Jones Cesspooch Jr., a homeless man once accused of killing another homeless man — people charged with murdering and raping, plotting and conniving, dealing and thieving.

The walls of Yengich's Salt Lake City office are filled with framed newspaper articles and verdict forms of some of his high-profile victories, among them: Sam Kastanis, acquitted of four counts of aggravated murder in 1993; Jackie Lee Byrd, a Murray businessman acquitted of murder in 1996; James Bottarini, acquitted of murder in 2002. He represented environmental activist Tim DeChristopher, convicted of placing bogus bids that disrupted an oil and gas lease auction. He is currently counsel for businessman Jeremy Johnson, accused of fraud and a central figure in the scandal engulfing Utah Attorney General John Swallow.

"Being a jackass, which I have always been, it has always been something to aspire to — that sensibility that is able to see goodness in other people in difficult situations," Yengich says. "You can project that forward and maybe see why I am a defense attorney, really."

It's a sensibility that was nurtured in him from the time he was a boy.

Yengich, 63, is a cradle Catholic born to Italian-Croatian parents. He grew up in the long-gone mining town of Highland Boy in Bingham Canyon and then Sandy. During his youth, Mass was celebrated in Latin, a lyrical language that Yengich fell in love with, still studies and, through sponsorship of an annual competition, encourages others to embrace.

It was as a boy, too, that Yengich gained an appreciation for the ritual of the liturgy, which "I now know and understand, as an old man, made me feel a tie to my people and my group," he says, people who were largely salt-of-the-earth types focused on "simple, good things."

After graduating from Jordan High, Yengich ended up with a scholarship to a Baptist school — Kentucky Southern College in Louisville, which primarily met his desire to get as far from Utah as he could. In 1969, a year after Yengich arrived, Kentucky Southern merged with the University of Louisville. Yengich transferred to Louisville's Bellarmine College (now university), a small Catholic school whose motto is "In Veritatis Amore" — In the Love of Truth.

College didn't solidify Yengich's faith as much as it did his thinking.

"The one thing that [Kentucky Southern] and Bellarmine did for me was to open up a desire to learn more about fundamental human relationships and never stop learning about that," he says. "And, I think, in Western civilization certainly, that means learning about religion and philosophy."

Bellarmine also exposed Yengich to one of the Catholic faith's most profound thinkers: Thomas Merton.

Merton, a Trappist monk who died in 1968, donated a large portion of his papers to Bellarmine, which created the Thomas Merton Center around the time Yengich arrived on campus. Yengich spent a lot of time in the Merton room in the old library.

"It isn't as though I sat there and contemplated the stuff that was in the Merton room, but I used to go there to study, and I felt a genuine connection with him to the extent that I used to joke, a long time ago, that I was a Zen Catholic."

One of Merton's big ideas, Yengich says, is "you just don't accept everything that someone else says necessarily on faith without challenging it. His whole deal was if you are seeking it, then you'll find it. But seeking isn't easy. There aren't any easy answers."

It's what many of the great mystics experienced, Yengich adds — what St. John of the Cross called the "Dark Night of the Soul." That is, "periods of questioning."

And Yengich has had his own.

—

From mostly out to all in • For a time Yengich, who returned to Utah to complete his law degree at the University of Utah, drifted from the Catholic Church — never left it, but slid into the lapsed category all the same.

He didn't go to church, didn't attend Mass, didn't participate in the sacraments.

"Although here's what I would do," he says. "I would find myself, when I was out of town, going to church or sneaking in and going to confession. Or always [doing] the simple sacramentals — lighting a candle. There's very seldom that I've passed a church in my whole life that I haven't gone in and lit a candle."

Yengich knows some people — the Christopher Hitchenses and Bill Mahers of the world — believe that's simplistic, even stupid. And that's fine with him.

"One of the things people who don't have faith lose is being bound to your story in the context of everybody else," he says. "A candle is lit so that you can pray for somebody. Well, that's a good thing because you are opening yourself up not to love of yourself, you're not doing it for you. You're opening yourself up to do it for somebody else, with the belief that there is somebody who is going to hear you about that.

"That's a simplistic view of religion, but it's an acceptable simplistic view because it can also lead you to reflect on what that really means. What does it mean? Well, it means that I actually do have faith," he adds. "Well, what does that mean? And then you start asking that question. And we put it in the context of our story and the history of who we are and that allows you to grow, and it makes you a better person in a sense and in another sense it opens you up, I think, to a deeper reality that says the greater joys in life really are when you, even in a simple way, put yourself out."

So he kept lighting candles and picking up a Mass here and there.

But he still wasn't all in, not until he had an epiphany. Here's what happened.

Yengich came across a story about a Catholic bishop in New Jersey who invalidated a child's First Communion because the parish priest had allowed the girl, who had celiac disease, to receive a rice wafer; that, the bishop said, was contrary to Catholic doctrine requiring communion wafers to be made of unleavened wheat.

The story brought out the "Joe Magarac" in Yengich.

Blood boiling, he spewed his indignation in a letter to the Intermountain Catholic, a weekly newspaper published by the Catholic Diocese of Salt Lake City, listing his grievances with the faith.

Yengich soon received a call from the diocese's bishop at the time, the Rev. George Niederauer, who invited him to lunch. Niederauer, now enjoying retirement along the California coast, remembers Yengich's "honesty and his earnestness and willingness to hear me out and consider things from a different perspective" but doesn't recall the details of their conversation.

Yengich does.

"I unloaded and I unloaded on the normal stuff, you know, women priests and gays and that stuff, and he was great," Yengich says. "He heard me out and at the end he goes, 'Well, what are you going to do about it?' "

Yengich goes silent for a few moments at this point in the retelling, head bent, and when he speaks again, his voice is a hoarse whisper.

"I said, 'What do you mean?' And he said, 'Well, you know, you're like a lot of people.' He said, 'You complain, but what have you done to change it other than complain?' "

The bishop advised that if Yengich wanted his voice heard, he had to be "in the arena."

Then, Yengich says, Niederauer noted, in "such a subtle, loving way," the changes and good works that lapsed Catholics often overlook: the hospices for AIDS patients the church operates around the world, the way it has given girls and women roles in the Mass, and so on. Yengich found himself nodding his head again and again and again.

"He said, 'You may not always be able to get everything that you think is right, but what's unfair from people like you is that you won't ever acknowledge what changes have been made that are consistent with your opinions as to what they should be,' " Yengich says.

"Uh-huh, you got me on that one," Yengich recalls thinking. "It was an eye-opener for me. It was not something I didn't know. It wasn't even something I hadn't read, but it was interesting to hear it from a man I respected, who looked me in the eye and said it. And then it was the game is on."

—

Of saints and sinners • Yengich starts each day with a cup of coffee and the writings of Thomas Merton.

In his cluttered law office, where nearly every inch of wall and desk space is covered with mementos of his storied legal career, sports and political treasures and family photos, you'll also find these: papal holy cards, a statue of the Virgin Mary, a coffee cup imprinted with a photograph of Pope Francis. He rattles off the names and sayings of Catholic icons — Teresa of Ávila, John of the Cross, St. Therese of Lisieux, St. Francis, Blessed Mother Teresa of Calcutta, St. Augustine — in a way that makes it clear they often are on his mind. There have been other influences on his spirituality as well, good people who were Mormons and Muslims, Baptists and Buddhists.

"There are a lot of people like that who make you reflect on your own story within the big story," he says, "and I admire them for their journey and what they've given to me as a Catholic, recognizing there are a lot of narrow roads to God, if you will, or enlightenment or whatever you want to say."

On Sundays, Yengich is an usher at the 8:30 a.m. Mass at Salt Lake City's Cathedral of the Madeleine. Since 2006, he has organized the Red Mass for Justice — this year it will be celebrated at noon on Oct. 11 — for those in the legal profession who share the Catholic faith.

Yengich the attorney, with his blue-collar roots, is a self-made man, one who "strives to look out for the little guy and is very much aware of the needs of those who are in desperate situations," says Monsignor Joseph Mayo, pastor at Draper's St. John the Baptist Parish.

Yengich the believer — the man Niederauer describes as a "committed seeker" — is a side that most people don't know, Mayo says.

"He does have a soul, he does have a heart," Mayo adds. "He understands the troubles of people's lives. He really does try to develop the value of the gospel as best he can."

In the years since his conversation with Niederauer, Yengich says he has tried to "be a good example" and has "failed repeatedly."

"I don't go to church because I'm perfect. I go to church in part because I am imperfect," he says. "The church is a church of sinners. We're not perfect people. But we at least are trying to be better and we are trying to be better people reflecting on our faith and our belief in God.

"We think of a religious conversion as something that happens once and then it's over, but that's not true," Yengich says. "The great writers on this, Catholic or Protestant or even Muslim or the great Hindus, the Vedas, the Buddhist teachers, all continually say that religion, God, is somebody that you are constantly seeking."

The transcendent moments come and go, but in Yengich's view the task is to keep after them despite falling short — or, in his own case, "being the evil, driven donkey that I can be."

"We've got to understand that we're going to fail and that we're not going to be as good a people as we want to be," he says. "But that doesn't mean that we don't try to be and don't realize that God still loves us. … I'm a much better person fundamentally because of that journey than I would be without it."

And with those words, the defense — of his faith and his allegiance to it — rests.

A Prayer to St. Teresa of Avila

Pray for me, St. Teresa,

That I will begin to drop all

attachments of the earth —

save for the love of my wife

and my family, given to me

by God —

and that in so doing,

I will practice my belief

in the faith that is

only LOVE;

LOVE which is God's real reward;

LOVE which (are) is the real

riches of our inheritance

as his children;

LOVE that has the only meaning

and really is what we are meant to pass on and

share as our gift to others

and our inheritance and our

bequest of this mortal life.

Ron Yengich —

Memorial

walk/run

On the first Saturday in December, attorney Ron Yengich puts on the Nick Yengich/Grandma Gump 5K Memorial Walk/Run in Copperton, close to the community where his family once lived. The event raises money for someone or something in need. Participants also are urged to visit the Methodist Church Bazaar that takes place the same day. The race is a tribute to Yengich's brother Nick, who died in 1984 at age 37, and to Geraldine Ennis, a former Draper judge and philanthropist.