This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

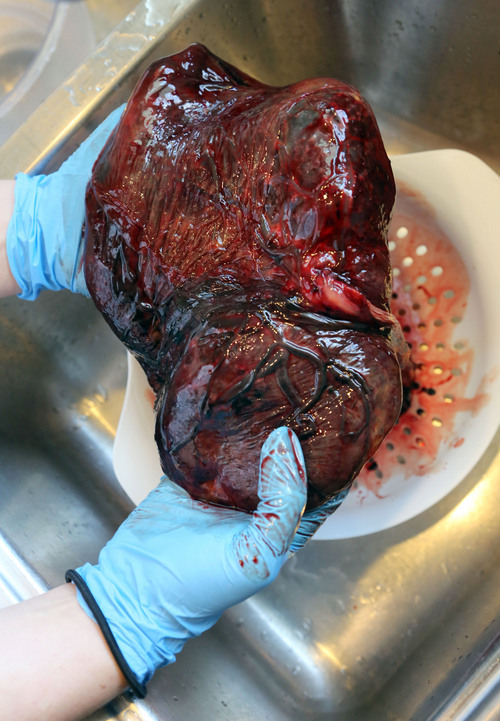

The air in Laura Curtis' kitchen is thick with the iron-rich smell of placenta.

The organ, an unusually large specimen, has been steaming atop a pot of boiling water, ginger and lemon and has turned an unappetizing gray. But soon the "mutant hamburger," as Curtis describes it, will be sliced, dehydrated, ground into a powder and capsulized for … you guessed it, human consumption.

Some women freeze it and add it to smoothies. Others roast theirs, adding it to soups and spaghetti bolognese. Most pay to have it encapsulated.

Human placentophagia, saving your placenta after birth and eating it, is not a nature-loving hippie thing, a rite of passage for primitive cultures, or a spooky Salem Society ritual. It's happening in Utah and elsewhere across the country, and with growing frequency.

It's a practice with no anthropological precedent, promoted by a chorus of moms swearing by its health benefits — despite a scarcity of research. And it has birthed a cottage industry of placenta preparers.

Utah hospitals don't keep track of how many moms ask to have their placentas packaged and put on ice instead of leaving them for incineration. University Hospital anecdotally pegs the figure at about 5 percent to 10 percent of its deliveries. Intermountain Medical Center gets a couple of requests each month.

"But it seems to be trending upward," said Bernice Tenort, nurse manager of University Hospital's labor and delivery ward.

—

'There's a demand' • For many, the thought of cannibalizing something expelled from your own body triggers a gag reflex. The placenta contains genetic material from the mother, the father and the baby.

But the practice has caught on among mostly white, married, middle-class, college-educated women, most of whom report positive experiences, according to a recent study in the journal Ecology of Food and Nutrition. It's also popular among women who choose to deliver their babies at home, the study found.

Because the organ passes essential nutrients from mother to baby and contains iron and helpful postpartum hormones, such as progesterone and oxytocin, it's assumed that ingesting it will confer benefits.

Parenting blogs and home-birthing websites assert it can decrease postpartum bleeding, help your uterus shrink, enrich your milk supply and prevent the baby blues.

"There are a lot of things we do to improve our health which haven't been studied and proven by medical science, and yet we know they work," said Curtis, a hypnobirthing instructor and owner of Utah's largest placenta encapsulator, PlacentaWise in Lindon.

"You can walk into any health-food store and find yourself surrounded by people who are taking their health into their own hands through supplements and herbs," she said. "... Placenta capsules are such a supplement."

Curtis learned how to encapsulate while training to become a certified doula instructor.

"It was odd and foreign to me and seemed icky and gross," she said. "I don't even touch meat. I'm vegan."

But patient testimonials persuaded her to give it a try. "There's a demand for this service and a need for people doing it safely," said Curtis, who follows food handling and occupational safety protocols.

—

A bonding treat? • None of this is backed by science. There have been a handful of observational human studies dating back to the early 1900s and animal studies — most, but not all, mammals eat their placenta — but no randomized trials.

"There are lots of things animals do that humans shouldn't do," said Mark Kristal, a psychologist in the behavioral neuroscience program at University at Buffalo.

There are plenty of theories as to why animals eat their placentas: to replace depleted nutrients or safeguard the nest from hungry predators.

Kristal, one of the few to study the practice, believes it has more to do with bonding.

"Animals do things because it looks good, feels good, smells good and tastes good," he said. "When the infant comes out in amniotic fluid, it increases the attractiveness of the infant, guaranteeing that the female interacts with it right away [by licking it clean]."

As a side benefit, eating the placenta also has an analgesic effect, easing the animal's pain, said Kristal. The active ingredient is a peptide, he said. "We know that, but we haven't identified it."

But anthropological surveys have found no evidence of the practice among humans, he said. "In any cultures where it's mentioned, it's mentioned as a taboo."

There is a placenta preparation used in Chinese herbal medicine, but in combination with other herbs and for a variety of disorders, he said. "There could be an evolutionary reason why humans don't eat placentas."

There's no proof that it's harmful, though.

"We don't advocate for or against it," said Tenort from University Hospital. "Our goal is to honor the patients' rights and to make their birthing experience the experience that they want to have."

A fair number of placentas wind up in pathology if doctors suspect an infection or anomaly, but legally the organ belongs to the mother, she said.

—

Raw, dried, or mixed with herbs • There are more than half-a-dozen encapsulators in Utah, mostly doulas and midwives. Some dry the placentas in their oven on cookie sheets. Others add medicinal herbs to the capsules, which Curtis eschews because they could trigger an adverse reaction, ruining the entire batch and wasting the placenta.

"I don't support the practice of eating it raw," she said, "because you're messing with bacteria that could be present."

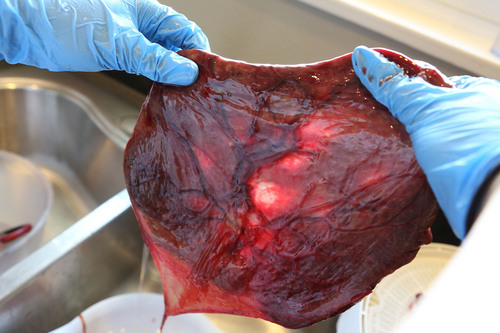

She rinses each placenta to remove blood clots and meconium, examines it for anomalies and steams it for 10 to 12 minutes each side.

All equipment and work surfaces are sanitized with a bleach solution. "I wear a fresh pair of gloves for every stage of preparation," she said.

Patients must keep their placenta refrigerated and arrange to have it delivered to her within 24 to 48 hours of the birth. And their doctor must sign a form detailing results of testing for blood-borne pathogens such as hepatitis or HIV/AIDS.

Customer satisfaction is high. She encapsulates about 18 to 20 placentas a month, upward of 200 since she opened shop in 2011.

The basic package, a bottle of capsules and an umbilical cord keepsake (a piece of the cord dried into the shape of a heart) goes for $200. For a little extra she'll also prepare an alcohol-based, placenta tincture that "keeps forever" and can be used to shorten menstrual periods, she said.

—

'My mom gut took over' • Provo resident Tiffany Strong, 32, was looking for something to avoid the baby blues she experienced with her first child.

"I was willing to try anything," she said. "My mom gut took over. There might not be that much research medically, but if all these moms say it works, and there isn't much risk, why not?"

With 8-month-old Dexter, she's had no bouts of sadness, freeing her from having to take antidepressants and worrying about whether they're safe for the breastfeeding baby.

"I take the pills whenever, one or two a day to boost my energy or if it has been a hard, stressful day," said

She has more energy and an abundant milk supply. "I know your second baby is supposed to be easier," she said. "I'm sure that has something to do with it, but I definitely notice the difference."

Amy Coffield said her placenta saved her life.

The 28-year-old was still suffering from postpartum depression with her middle child when she became pregnant with a third. "I never wanted to hurt my kids, but all I could think about was dying," she said of the depression that lasted through her pregnancy.

Four weeks after her baby was born and she started taking her placenta pills, however, Coffield said she "felt completely fine. I was happy, enjoying my kids and managing my duties as a mom and wife. I had no idea life could be this wonderful."

She and her husband are making a documentary about placenta encapsulation, and she recently attended one of Curtis' encapsulation training seminars.

Curtis welcomes regulation of the industry. Encapsulators aren't currently monitored by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration because they provide a service, not a product.

"This is not some crazy fad," she said, "or something that burns out in a couple of years." —

Au naturel?

Human consumption of placentas is a modern practice that appears to have arisen with the home-birthing movement. Popularized by celebrities such as "Mad Men" star January Jones and Kim Kardashian, it is capturing the imagination of mainstream America.