This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

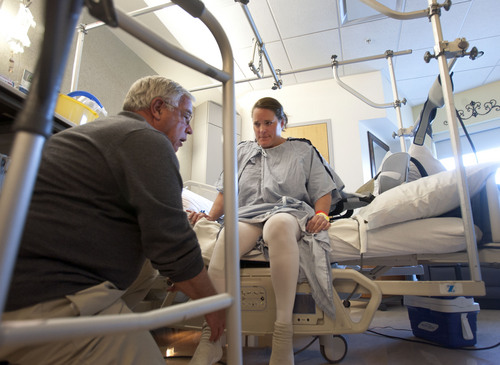

It has been less than 24 hours since Julie Harris had her right knee replaced, and the University of Utah Hospital patient is walking the recovery ward halls.

"This is good. You're doing great," coaxes her physical therapist with an approving nod from U. orthopedic surgeon Christopher Pelt. He predicts she'll be discharged the next day.

Early mobility has long been documented to speed recovery, ease pain and decrease chances of complications, such as blood clots and infections, explains Pelt.

But until recently, this standard of care wasn't uniformly applied at the U. — not because providers willfully ignored it, but because they didn't know they were wavering from it.

A new data tool developed by the U. is helping doctors and surgical teams visualize when they stray from protocols by shining a light on the costs racked up by their patients. It's sparking conversations about how to deliver better care more efficiently.

And though it's less than a year old, it's making a measurable difference, said Vivian Lee, senior vice president at University of Utah Health Sciences. Over just six months in 2013, provider teams brainstormed more than 500 strategies to streamline care, projected to save $7.1 million annually.

"There's been a lot of press lately about charges, the price tag we stick on our services," said Lee, referring to articles such as "Bitter Pill," Time magazine's exposé on hospital markups, such as charging $25 for a Tylenol pill.

"But the bill is just a made-up number. The true problem in health care is we don't understand our costs," said Lee. "If you don't know your costs, you can't drive down health spending in this country."

—

What will this cost me? • It seems remarkable, even unbelievable. Imagine a car manufacturer not knowing how much a windshield costs or a unit of labor.

But there hasn't been an imperative for hospitals to know, explains industry consultant James Orlikoff, known in health care circles as Dr. Doom.

"Until recently hospitals were rewarded for being inefficient, because the more inefficient they were, the more they were reimbursed," he explained, referring to the fee-for-service model that pays providers for ordering more tests and treatments.

Because charges are divorced from actual costs, some services are priced as high as the market will bear, he said, while others are reimbursed below cost, or not at all.

But consumers, employers and the government have started pushing back.

"Consumerism is being injected into health care," Orlikoff said. "People are demanding to know, 'How much will this procedure cost me? And don't say my insurer will cover it, because I'm now having to pay more of the bill.' "

—

'The value equation' • Our health system is bloated and broken, Orlikoff said. Americans spend an estimated $2.8 trillion on medical care, including $750 billion on wasteful treatments, the Institute of Medicine reported in 2012.

And medical errors are the third leading cause of death, surpassing auto accidents and diabetes and killing an estimated 440,000 in the U.S. annually, according to a 2013 study in the Journal of Patient Safety.

"My dream," said Lee, "was to create a tool that would give us outcomes against cost, because that's really the value equation."

Working with the university's business school and computer science experts, the U. built what Lee calls the Value Driven Outcomes (VDO) tool. The system can run each patient against 135 million rows of billing and payroll data to show the cost of every procedure, or episode of care — from gauze tape to minutes of nursing labor — and reveal differences from one U. provider to the next.

It is also able to integrate quality data, such as rates of mortality, readmissions, bleeding and infection.

"For any patient that comes through our system, whether for an appendectomy or joint replacement, we can break down the cost of their care," said Lee. "We can look at how much of it was the prosthesis, operating time, physician time, drugs, imaging and length of stay."

The U. found that for any given procedure, there's at least a twofold difference from the highest-cost to lowest-cost provider.

"What this allows us to do," Lee explained, "is get all of our orthopedists in the room and ask: Why are you ordering this prosthesis that's twice as expensive? Why are you getting an X-ray on day three when none of your colleagues are doing that?"

—

Fear of 'widget' care • Using data to drive health care decisions, instead of just relying on an individual doctor's training and instincts, isn't new. Intermountain Healthcare has been doing it since 1986 under the leadership of Brent James, a former cancer surgeon and the hospital chain's chief quality officer.

James is widely viewed as a pioneer of evidence-based medicine. "At Intermountain," he said, "we have developed about 60 care pathways [or protocols] covering 80 percent of all procedures done at our hospitals."

But academic medical centers have been slow to embrace the paradigm, said James. "The challenge that Vivian Lee is up against is a longer 'craft of care' tradition in academia. I give her credit for taking a crack at it."

Standardizing medicine has been perceived as treating patients like cars or widgets and academicians are data skeptics, said Robert Pendleton, the U.'s chief medical quality officer.

But once the U. was able to prove the integrity of its data, the numbers spoke for themselves, he said. "It has been incredibly engaging."

Some fixes are obvious. VDO revealed, for example, that a commonly prescribed $200 bronchodilator, which increases airflow to the lungs, worked no better than a similar drug for $15. Switching to that drug is projected to save $200,000 a year.

The tool has also spotlighted unnecessary MRIs for back pain and prescriptions for the wrong types of antibiotics. It has armed the hospital to renegotiate prices for medical devices. And it's helped nurses develop ways to more quickly prepare patients for surgery, sparing them delays.

—

Spotting the gaps • But some solutions require more digging.

Data on joint replacements showed wide variation in cost from provider to provider, and less than a $5 difference between the two surgeons at the U. who do the most hip and knee replacements, including Pelt.

Orthopedic teams — surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists, therapists and support staff — met to identify best practices and barriers to implementing them.

One clear outlier was a surgeon who was using an implant that wasn't under a discounted contract, which they persuaded the doctor to stop using.

Trauma and cancer surgeons with more complicated patients also showed higher costs. The group removed those doctors from the analysis and discovered another, more worrisome source of variation: hospital stays.

"We asked, 'Are we keeping some patients longer than they need to be, and if so, why?' " said Pelt.

Surgeons agreed that having patients walk on the same day of surgery was critical to shortening hospital stays. But in talking to physical therapists, they learned most ended their shifts at 3 p.m., making same-day therapy impossible for some patients.

The remedy: Schedule a therapist to work an afternoon swing shift.

Today 90 percent of joint-replacement patients at the U. get their first dose of therapy on the same day of their surgery, up from 45 percent.

All doctors want to provide the best care to their patients, said Pelt. "Data helps you visualize the gaps."

—

A system out of alignment • Harris was grateful to return to her Salt Lake City home sooner to recuperate in comfort. "I'd just like to be able to play a game of golf or walk around the mall without pain," said the 46-year-old, who was diagnosed with arthritis at age 14.

She's scheduled to have her other knee replaced next year. A shorter hospital stay will, no doubt, mean a cheaper bill.

But it will take time for reduced expenses to truly bend the cost curve and translate to affordable health insurance.

"It's this misaligned system we have," Pendleton said. "If a patient has commercial insurance and we order fewer tests, that's money we're losing. If a patient has Medicare, which pays a fixed sum for a procedure that we're able to do more efficiently, the hospital wins."

And until hospitals publicly disclose their costs and prices, he said, consumers won't really know what kind of deal they're getting — if any.

"We don't publish our costs. We believe complete transparency will eventually be necessary, but it's like playing a game of poker," said Pendleton. "If you know your costs and put them all on the table, you're at a potential disadvantage if your competitors don't offer the same degree of transparency."

The ideal, he said, would be for patients to shop for procedures by comparing costs and expected outcomes.

"We're a long way as an industry from getting there," Pendleton said.

—

New negotiations on costs • But Orlikoff said changes are happening faster than anyone imagined, and hospitals that don't have a handle on their costs won't last.

Large employers, such as Wal-Mart, are starting to contract directly with hospitals to handle heart or spinal surgeries. "They're telling employees you can go anywhere, but if you go to these six centers of excellence, we'll pay for everything, including airfare for you and your family," he said.

Insurers are also encouraging patients to shop around by paying a flat fee for certain procedures. "Go where you want, but if it costs more than the allowed amount, you'll pay it, and if you go somewhere cheaper, it will cost less," Orlikoff explained.

"It used to be that insurers negotiated payment down from charges so the incentive was to have high charges," he said. "Now we're talking about negotiating from cost, from the bottom up."

Medicare already does this to some extent, so hospitals that can't break even on its rates today may not survive.

"You're going to see massive consolidation and closures. It's already happening. We have 1,000 fewer hospitals in the country than we did in the 1980s," Orlikoff said. "It's a real mess and anyone who tells you they know what the health care system will look like in 10 years is lying."