Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon M

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon M

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon M

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon M

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

A 320-ton truck, which has been the backbone of remediation efforts at Kennecott, cas

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

A 320-ton truck, which has been the backbone of remediation efforts at Kennecott, cas

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

The 320 ton trucks at Kennecott have been the backbone of remediation efforts at Kenn

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

The 320 ton trucks at Kennecott have been the backbone of remediation efforts at Kenn

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

The 320 ton trucks at Kennecott have been the backbone of remediation efforts at Kenn

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

The 320 ton trucks at Kennecott have been the backbone of remediation efforts at Kenn

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly 6- months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mi

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon M

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon M

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Kennecott mine General Manager Matt Lengerich talks about the efforts made for a near

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

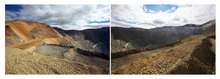

Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecottís new 150-foot-wide mine access ramp. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that occurred April 10.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecott's new 150-foot-wide mine access ramp. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that occurred April 10.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecott's new 150-foot-wide mine access ramp. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that occurred April 10.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecott's new 150-foot-wide mine access ramp, at far left. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that occurred April 10.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

A 320-ton truck, which has been the backbone of remediation efforts at Kennecott, casts a long shadow. Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecott's new 150-foot-wide mine access ramp. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that occurred April 10.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

A 320-ton truck, which has been the backbone of remediation efforts at Kennecott, casts a long shadow. Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecott's new 150-foot-wide mine access ramp. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that occurred April 10.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

The 320 ton trucks at Kennecott have been the backbone of remediation efforts at Kennecott. Nearly 6-months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecott's new 150 ft wide mine access ramp. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that shut down operations for 17 days.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

The 320 ton trucks at Kennecott have been the backbone of remediation efforts at Kennecott. Nearly 6-months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecott's new 150 ft wide mine access ramp. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that shut down operations for 17 days, seen in background.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

The 320 ton trucks at Kennecott have been the backbone of remediation efforts at Kennecott. Nearly 6-months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecott's new 150 ft wide mine access ramp. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that shut down operations for 17 days.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

The 320 ton trucks at Kennecott have been the backbone of remediation efforts at Kennecott. Nearly 6-months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecottís new 150 ft wide mine access ramp. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that shut down operations for 17 days.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly 6- months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecott's new 150 ft wide mine access ramp as an earth mover continues work on the slide that started near the upper left hand side. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that shut down operations for 17 days.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecott's new 150-foot-wide mine access ramp. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that occurred April 10.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Nearly six months ahead of schedule, top-to-bottom access within the Bingham Canyon Mine returns with the opening of Kennecott's new 150-foot-wide mine access ramp. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that occurred April 10.

Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune

Kennecott mine General Manager Matt Lengerich talks about the efforts made for a nearly 6-months ahead of schedule access for top-to-bottom movement within the Bingham Canyon Mine with the opening of Kennecottís new 150 ft wide mine access ramp. On Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2013, mine operators granted access to see the progress that has been made with 14 million tons of material removed so far following the 150 million ton slide that shut down operations for 17 days.