This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

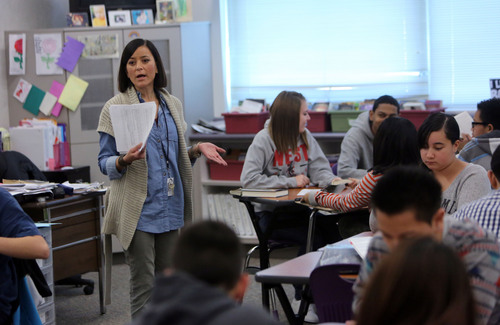

The 780 students at Northwest Middle School face myriad challenges.

Ninety-two percent come from low-income homes and 87 percent are ethnic minorities. Nearly two-thirds don't speak English at home.

And yet, three years after receiving a $2.3 million multiyear school-improvement grant, the west-side Salt Lake City school has risen from the bottom to the top tier of Utah junior high and middle schools in student achievement.

The remarkable turnaround at Northwest is drawing national attention: U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan is touring the school on Thursday and engaging parents, students and educators in an hourlong discussion.

"In a short amount of time, not decades, you had radically, radically different results," he said at the school Thursday morning. "I want to hear that story, about how you guys have done this."

The school's "phenomenal, phenomenal progress" has "national implications," he added, as turning around schools is some of the hardest, sometimes the most controversial, work educators face.

Northwest is the only school Duncan is visiting on his trip to the Beehive State.

The dramatic change began in 2010, when Northwest was awarded the $2.3 million grant by the Utah Office of Education. Most schools serving such students get several hundred thousand dollars in Title I federal money; this was an extra grant from Title I funds for concentrated improvement.

At the same time, Northwest got a $1 million technology grant from federal funds.

The money made a big difference, says Principal Brian Conley and Rachel Nance, a vice principal.

But mostly, it served as a jumping-off point, a door between the old way of doing business and the new.

"It's way more than money," Nance says.

—

A new strategy • Conley came to the school in fall 2013 from the district office, where he had been overseeing 11 elementary schools.

He began by demanding teachers and staff foster a new culture that didn't rely on tired stereotypes that set a low bar for low-income and minority students.

Seven of the school's 40 teachers left right off the bat.

In fact, half the school's teachers are new hires made in the past three years; some left on their own and some didn't cut it, says Conley.

Generally, teachers who were too rigid to change the way they teach, or more passionate about their subjects than student learning, are gone, he says.

"If you're going to teach here, you have to bring your A game every day," says Conley. "We have these students two years. We work like our hair is on fire."

Before, teachers worked as if they were on islands, he says.

Now, they are in teams that meet regularly to go over data that show which concepts students aren't understanding, based on before-and-after testing on core curriculum. They drill down and target students for extra help, and they discuss whether methods work.

The school's technology — 600 netbooks, a Smart Board in every classroom, wireless Internet throughout the school — is a great tool, he says. "We became more generationally relevant."

At year's end, teachers get performance bonuses based on student achievement.

There's an all-school bonus and possible extra bonuses for teachers in the high-stakes disciplines such as language arts (English), math and science.

In the past three years, teachers have had bonuses ranging from $1,500 to $8,000 at year's end, Conley says.

Performance pay is controversial, even among Northwest's teachers. They disrupt the culture of "nice and equal," he notes in a letter summarizing his school's achievements.

Nonetheless, he and assistant principals Nance and Pam Pedersen are committed to that and other changes.

"For those who still resist," they write, "we will continue to coach them up or coach them out."

—

Two kinds of fun • Students in Rob Dahl's eighth-grade science class agree that their school does have an atypical culture: Being smart here doesn't make you a nerd. It makes you cool.

Salim Orduno is in the Warrior Club for those with 3.2 grade-point averages or better. Its membership has risen from about 270 three years ago to more than 500 today.

"Here you get rewarded for being smart," says Orduno.

Nando Hamzic agrees.

Knowing more puts one in a better position to argue a point, he says. "Learning is cool. You know more stuff."

Conley says creating that culture requires constant reinforcement and incentives.

At the start of the school year, he and teachers talk with students about the two kinds of fun: unstructured time with friends, and the fun that comes from mastery of a concept or subject. Just as it's fun to excel at a video game, it's fun — and life is easier — if one excels in academics, he says.

Just as teachers are all about data, so are students, he says.

During assemblies, administrators will drop a jumbo screen and show charts and graphs to foster friendly competition.

One time, the data may show that seventh-graders are tardy less often than eighth-graders; the next screen might show data comparing girls' and boys' reading scores.

Counselors tell students where they rank in their class as a way to encourage harder work.

The after-school program now has more than 200 students participating, up from 80 three years ago.

Two days a week, struggling students are taught by top teachers after school, and two other days of the week, any student can stay for "exploratory" classes such as soccer, lacrosse, yearbook, sewing, band and winter-sports conditioning. One afternoon this week, for instance, students went snowshoeing.

These measures, Conley says, help students learn that making their own change is preferable to having change imposed on them.

The school expected 685 students this year, but has 780; the principal believes neighborhood families are bringing their children back to Northwest.

—

Spread the pay • The school-improvement grant is gone now. Northwest will still have performance pay bonuses this year, thanks to a $100,000 grant from the Salt Lake City-based Educational Reform Foundation and a piece of the school's regular Title I money.

But earlier this week, Conley made a pitch to the Salt Lake City School Board to put 1 percent of its budget next year, $2.4 million, toward performance pay in a select number of schools.

That way, the district could show the Legislature how it's done, he says.

"We're not smarter than any other administrators," he says. "We're just tenacious."

Twitter: @KristenMoulton —

Gains at Northwest Middle School

Math • Three years ago, only 37 percent of students were proficient on end-of-year tests. Last spring, 79 percent were proficient.

Science • Fewer than 4 in 10 (38 percent) of students were proficient on end-of-year tests in 2010; 58 percent were proficient last spring.

English/ language arts • Roughly 80 percent have been proficient on end-of-year tests for four years, but students were reading on average at a fourth-grade level in 2010. They now read at a seventh-grade level. Only 15 percent were considered proficient in writing four years ago; this year, 86 percent of eighth-graders were proficient.

Attendance • More than 90 percent of students have satisfactory attendance, and tardiness has been cut in half over three years. —

Do you know an innovative teacher?

KUED-Channel 7 and The Salt Lake Tribune are looking for nominations for upcoming Teacher Innovation Awards, recognizing educators who are using digital media to improve students' learning.

Teachers from across the state can be nominated in five categories: arts, math, reading and language arts, science and social studies. Learn more at kued.org/nominate.