This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

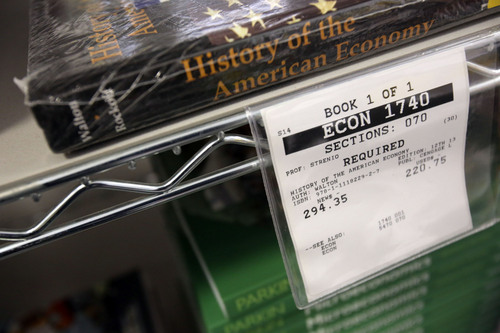

For $150, a University of Utah student could buy a few tanks of gas, a couple of weeks' worth of groceries — or maybe a textbook for an English class.

"[Books] can be a financial burden," said Rachel Wootten, a geography and political-science major.

The cost of textbooks has risen a staggering 812 percent since 1978, according to an analysis by the American Enterprise Institute. At the U., the average student cost for books and supplies is $1,000 a year, on top of nearly $7,000 a year for in-state tuition.

"The prices are just ridiculous in my opinion," said Dave Nelson, book manager at the university bookstore. "They're just nuts, how much they're going up."

But a new U. Academic Senate committee wants to do something about it. The group last week voted to explore saving students money by using open-source textbooks — books licensed to be downloaded for free online. Senate president Allyson Mower, a U. librarian, said she's aiming to cut costs by $500 a year.

"That's huge," said Sam Ortiz, president of Associated Students of the University of Utah. "I'm excited just that we're having the conversation."

There are some challenges to using free textbooks, though. The availability and quality of the material can vary, and they can require a bigger time investment from instructors.

But Ethan Senack, a higher education advocate with the Public Interest Research Group (PIRG) in Washington, D.C., calls open textbooks the "ideal solution" for introducing more competition and bringing prices down.

"The textbook market is broken," said Senack.

Buyers don't make purchasing decisions, he said, but buy what they're told by professors, removing some urgency on lowering prices. And when instructors make those determinations, they often have only $200 books to choose from.

But the production of free books relies on professors who are willing to write them, usually for free, and instructors who edit and adapt them for a particular course.

"For both writers and adopters, if you're a teacher, the issue is time," Jacky Hood, co-director of the Open Doors Group and College Open Textbooks, told the Chronicle of Higher Education in January. "You're going to need a term off to either author or adopt a textbook, and that requires some kind of funding."

But David Wiley, a professor on leave from Brigham Young University who studied use of open textbooks at Utah's public schools, said there are already enough resources to teach lower-level courses.

"If any university in the country today just wanted to ... say, 'We're never going to require students to pay for a textbook for a general education course again,' any school in the country could say that today," he said.

In a study, Wiley found there was "basically no difference in the amount students learned" using open textbooks — and it saved the districts about 60 percent in book costs.

The new Academic Senate committee will also look at other options for lowering books costs, such as a textbook exchange. The U. bookstore already offers some methods to save money, such as semester-long book rental for half the price of a new volume and a system that lets students compare bookstore prices with online costs to make sure they're getting the best deal.

Nelson said the store also has one the highest percentages of used books in the country — about 45 percent — which cost about 25 percent less than new.

The committee will report its findings in April.

Twitter: @lwhitehurst