This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Brian Scott knew the "science wasn't there yet," that his pursuit of an alternative cannabis treatment for his cancer was reaching for a "miracle," said mom Jane Scott.

"We had our eyes open. We just had to go with what we felt was right," Jane said Tuesday morning, hours after Brian's death from acute myeloid leukemia.

Brian, 20, died at home surrounded by family and at peace with his decision, said Jane.

"He never gave up. You never give up on a miracle. Miracles happen every day," she said. "But toward the end it wasn't looking good and he knew it wasn't looking good."

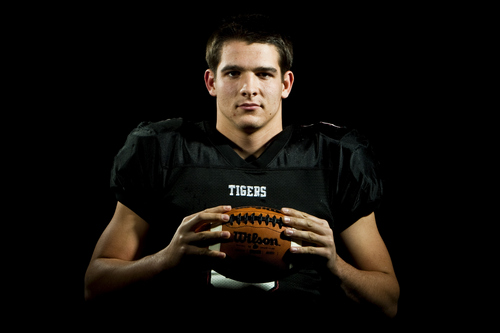

His death — like his diagnosis in the fall of 2012 — shocked friends and others who knew Brian as a powerful wrestler, football player and discus thrower at Hurricane High.

"This kid, if I was to say, was the most valuable athlete who ever came out of our school," said Kerry Prince, who coached Scott in wrestling for several years. "He was well-mannered, a pleasant kid to be around with a heart of gold. It's just hard to understand. You don't understand why someone with such talent and abilities, who had his whole life ahead of him, had to go through leukemia."

Laycee Johnson, whose young daughter, like many in southern Utah, spearheaded fundraisers for Scott, said, "Every little kid looked up to him."

Scott was just 18, a 2012 graduate of Hurricane High with a full-ride football scholarship to Southern Utah University when health problems were detected during a physical exam for an LDS mission to Uruguay.

The 225-pound fullback who carried the Hurricane Tigers to their first state championship endured six months of chemotherapy.

But the aggressive cancer of the blood returned. Midway through a second round of treatment at Primary Children's Medical Center, Scott — believing the chemo would kill him — stopped treatments, and refused a stem cell transplant.

Instead, he moved to Colorado last fall, and began taking cannabis pills from Realm of Caring Foundation, a nonprofit that cultivates marijuana and extracts a chemical component that some believe can arrest cancer as well as relieve symptoms. Other Utah children, too, have gone to Colorado for such treatments.

At the time, his mother said, "Death is a possibility with or without the chemo… and we all decided if he lives, he will have a life and won't just be fighting a disease for years on end."

At Primary Children's, it's not unusual for families to stop traditional medical treatment when cancer returns and hope for a cure is dim, said Richard Lemons, chief of the hematology/oncology division at Primary Childrens.

About 85 percent of children with cancer are cured.

The hospital works with families when they want to add alternative or complementary therapies such as other medicines, herbs, juices, essential oils or acupuncture. Those can reduce side effects of the cancer or the treatments, he said.

When families decide to end medical treatment, "Our job is to be supportive of the family in that decision," Lemons said.

There has not been enough peer-reviewed research into cannabis to know whether it can be effective in treating cancer, he said. One study at the University of Colorado at Boulder shows promise, but it was only in a laboratory and did not involve humans.

"That's an area where more research needs to be done," Lemons said.

Jane agrees and says state and federal laws need to change to allow for more research. She said the cannabis oil eased Brian's nausea and pain and helped him recover from his chemotherapy.

He regained enough strength to bike and hike and make a trip to the Coral Pink Sand Dunes in Kanab with his five brothers, said Jane. "That was fabulous, a memory he treasured."'

Last September when his cancer resurged, Brian agreed to reconsider a transplant and resumed chemo at the University of Colorado in Denver.

But he declined rapidly. "In December they told us, 'There's nothing we can do for your son,'" said Jane.

The family arranged to fly Brian home for blood transfusions at Dixie Regional Hospital. "We wanted him to have enough time to say goodbye to family and friends," said Jane. "He was able to spend Christmas Eve at home."

Jane struggles with moments of doubt, but said her son stood firm in his resolve. "He told me, 'Mom, don't you go there. We both decided this is what we were going to do,'" she said.

Doctors at Oregon Health & Science University tested more than 100 drugs on his blood cells and none showed promise, Jane said. "He had a stubborn [cancer] that outsmarted all the chemo."

Brian was an inspiration even to those who didn't know him personally.

"He fought valiantly," said Abraham Thiombiano, a St. George real estate specialist who hosted a dance that raised $1,000 for Brian. "The one thing I take from him: He's a fighter whether on the football field or in life."

Johnson said he was a "hero in all of southern Utah." Her daughter, Jannica, was just 9 when Scott was first being treated at Primary Children's.

Jannica came up with the idea for a bake sale, and she and her mother made muffins and rolls and hot chocolate, raising $300. When Jannica sent Brian the money, he sent back a thank-you note, which she treasured.

"She says a prayer for him every night. She would check (his mother's) blog every week." Johnson said. "It's going to be hard to tell her."

Tribune reporter Bubba Brown contributed to this story. —

Ceremony to honor Brian Scott

O Brian Scott's family hasn't finalized funeral arrangements but will hold a ceremony Saturday at 10 a.m. at the LDS Church stake center in La Verkin. The public is welcome. —

Medical marijuana

Brian Scott's death comes as a growing number of states move to legalize marijuana for medicinal purposes. Marijuana remains illegal in Utah, but lawmakers are considering making a "hemp extract" available to children with epilepsy.

Recent stories:

Slow-growing plant yields marijuana designed for kids, Nov. 10, 2013