This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Being a fraud victim can be financially and emotionally devastating — then you get sucked into the U.S. legal system.

For some investors, the experience can be maddening as they watch lawyers and accountants eat up $380 an hour and more in fees and expenses paid from recovered investor money as cases drag on.

But for some investors who are left with little money when the scam they invested in falls apart, the system of court-appointed receivers taking over fraudulent operations can work wonders in getting back at least some of their funds — even if it sometimes takes years.

The system isn't broken and offers the only hope for some to get any of their money back, according to some participants and observers.

But questions persist about possible conflicts of interest, lack of investor participation, a scarcity of information on which to weigh the efficiency of receivers' actions and the malleability of the system, for good and ill.

"We could complain and whine on a number of levels because we have lost money," said one investor in the giant Management Solutions case involving owner Wendell Jacobson.

"And it's not hard to identify a variety of perceived injustices, but the most galling aspect of this whole mess is that we feel more victimized by the legal system and the government than by Wendell Jacobson."

—

Awash in fraud • Financial fraud has crested in Utah in recent years, much of it forced into the open by the bursting of the housing bubble and the Great Recession. The wave has produced hundreds of victims, many of whom lost a great deal if not all of their major assets. Homes have been foreclosed on and entire retirement funds erased.

When the Securities and Exchange Commission files a lawsuit alleging fraud against a business and its owners and operators, it may ask the federal judge presiding over the case to appoint a receiver to assume control of the business, examine its records and recoup as much money as possible for distribution to investors.

Receivers are paid with money they can gather into the receivership from the cash left in accounts, sales of assets and "clawbacks" from investors who had gotten back more than they put in or those who inappropriately received money for fees or services. If there's not enough money to pay the bills, the receiver, lawyers and others don't get paid.

"You have an appointed duty to finish whether you get paid or not," said attorney Wayne Klein, who said as a receiver he's even loaned money to his receiverships in an attempt to keep them going so he can recover more money.

—

Cash back • One success story is Impact Cash of Logan, the company the SEC sued in 2011 over allegations owner John Scott Clark operated it as a Ponzi scheme in which money from new investors went to pay off earlier ones.

U.S. District Judge Dale Kimball appointed forensic accountant Gil Miller as the receiver.

Miller found an intact payday loan business that he sold back to investors. Funds from that sale and other monies collected likely will mean investors get 100 percent of their money back, though some pending issues in the case have held up distribution of all of the recovered funds.

"I am still confident that cash will be released and I will be able to pay investors 100 cents" on the dollar, Miller said.

As of the end of 2013, Miller had collected $23.3 million, while paying out $2.56 million in professional fees. Miller is billing $275 an hour in the Impact Cash case, while his lead attorney, Robert Wing, is billing at $330 an hour.

—

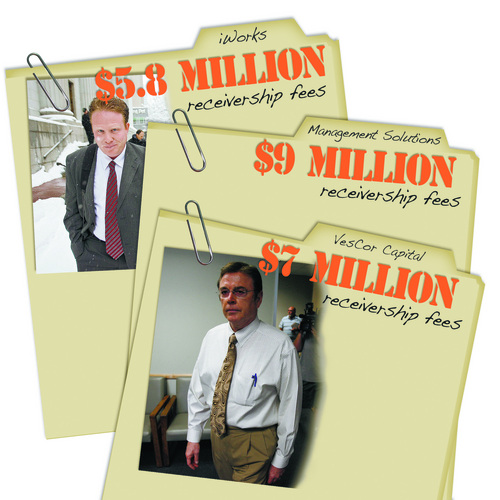

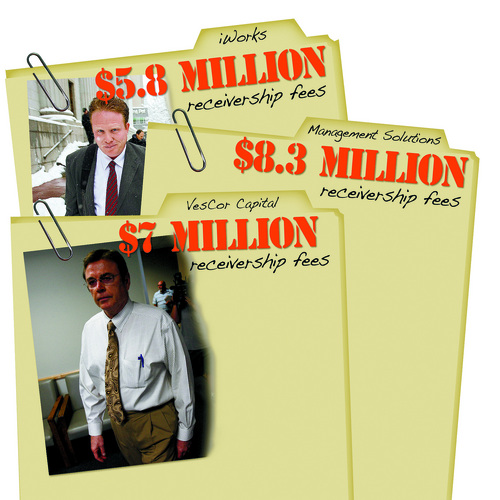

Angry investors • Two high-profile Utah cases have riled some investors.

They have similar characteristics. They are huge, complicated and expensive, likely the two largest financial frauds in Utah history.

Their size has slowed recovery efforts and strained relations between some investors and receivers. Critics say they point to a need for some changes in the system.

The SEC sued VesCor Corp. and owner Val Southwick in 2008 alleging he was operating his real estate development company as a Ponzi scheme.

More than 800 victims were left without an estimated $200 million or more that they invested before the company filed for bankruptcy in 2007.

Wing, the attorney in the Impact Cash case, was appointed receiver and his law firm, Prince Yeates & Geldzahler, was hired as legal counsel.

So far, Wing, who charges $250 an hour for this case, has invoiced $1.29 million for his services as receiver in the VesCor case, Prince Yeates has billed $3.56 million and Miller, hired as the forensic accountant, $971,079. Including other expenses, the receivership has billed for $7 million, or nearly half what it's recovered.

The SEC has proposed a plan to distribute the remaining $8 million to investors, ensuring all of them get at least 22.8 percent of their funds back. Wing expects to recover around $2.5 million more.

In 2011, the SEC sued Management Solutions Inc. of Fountain Green and its owners, Wendell and Allen Jacobson. The suit alleged the company, which had invested mostly in apartment complexes around the country, was operated as a Ponzi scheme, though that label hasn't quite stuck.

Some 225 investors poured about $220 million into the company.

Attorney John Beckstead was appointed receiver and his firm, Holland & Hart, became his legal counsel.

Beckstead charges $375 an hour and has billed for $1.1 million so far, Holland & Hart $4.8 million, the forensic accounting firm Deloitte Financial Advisory Services $2.5 million and another accounting firm, Wisan, Smith, Racker & Prescott, $742,808 for a total (with some smaller additions) of $9.3 million.

—

Conflicts? • Karen Martinez, director of the SEC Salt Lake City office, said the agency tries to match its recommendations for receivers to the needs of a particular case.

"Third-party receivers are overseen by courts, which determine if fees are reasonable and actions are justified regardless of whether or not a receiver is using his or her own firm," Martinez said in a statement. "When we make recommendations to the courts about which receivers they should consider choosing, our intent is to get as much money as possible back to harmed investors through a receiver with the necessary expertise to locate accounts and other assets in frauds that often can be difficult to unravel."

One criticism of the system is that receivers can and do hire their own law firms, potentially creating a built-in conflict of interest.

Receivers say hiring their own firms makes for some efficiencies because they have the expertise needed for complicated cases and they are in close physical proximity for more efficient interactions.

But when a large pool of money is available to pay receivership fees, critics say the receivers have incentive to bill for themselves and their firms, even for actions that cannot possibly recover even enough funds to cover the legal costs.

In Management Solutions, investors have banded together and hired attorney Greg Hoole to represent their interests in the case.

The investor group asked the court to order Beckstead to account for expenses for each clawback case he pursues in order to be able to gauge whether they are an efficient use of investor funds. Hoole pointed to the potential recovery in five lawsuits that was only an average of $3,482.

"The system is broken and there is one winner, the receiver and his law firm," the investor group said in an email. "The worse he does the more he makes. There does not seem to be any controls on this train."

Beckstead said in an interview that poor bookkeeping often makes it impossible to know in many cases how much any one investor has gotten back without some type of investigation. Investors sometimes don't cooperate in turning over information.

"If I don't go after people who owe money I'm criticized for not going after them," he said. "If I go after them for money I'm criticized for spending money going after them."

—

Checks • Wing, Beckstead and others point out there already are built-in checks in the system. The SEC examines their bills before they are submitted to the judge, who also can determine how much to pay and how much to trim.

U.S. District Judge Bruce Jenkins, who has been on the federal bench for about 40 years, said in an interview he believes the receiver system works overall, though each case presents different challenges.

"They're costly," Jenkins acknowledges, but the rates are generally what prevail in this area "and one of the features of the whole process is to have folks justify the costs."

Jenkins has a reputation for his hands-on supervision of receiver cases that end up in his courtroom, including Management Solutions. He spoke generally of receiverships and not any specific case.

Jenkins said courts have made an effort to be transparent, with invoices filed by the receiver available for inspection and hearings open to anyone. Investors or others can object to any receiver bill, he said.

Others point out many investors don't have the money to hire an attorney to file objections.

—

Years later • Wing has come under criticism as the VesCor case has dragged on for nearly six years and receivership costs have reached $7 million.

Jonathan Horne, a retired orthopedic surgeon and one of the biggest investors in VesCor, has been probably the most vocal critic of Wing's receivership.

"They [receivers] don't mind" the delay, said Horne, who was sued by the receivership. "They just continue to crank out the money to themselves and put the [investors'] money on hold."

Wells Fargo also recently intervened in the VesCor case and asked Judge Dee Benson to order Wing to turn over rent monies he has been collecting on a Nevada building he took over after failed negotiations with former VesCor business associate Christopher D. Layton. Layton's attorneys blamed Wing for the failure after a daylong session mediated by the SEC.

"As with other parties and lawyers in town, we have found it difficult to achieve a non-litigated and therefore cheaper, quicker resolution with the receiver," attorney Kristy Kimball said in an email. " This, of course, naturally leads to concerns about whether the receivership estate is being administered in the most cost-effective manner possible."

Wing blamed the default on what he said were only vague promises to pay a cash settlement and said he's determined that no investor money will be spent on the building.

—

Fire sale? • Beckstead proposes the sale of most of the Management Solutions apartment buildings for $338.5 million to an Atlanta-based company, though mortgages and other expenses must be paid from that amount and perhaps other fees such as loan prepayment penalties.

Still, along with additional property sales and other actions, the receivership could bring in a considerable amount of money to repay investors, though Beckstead declined to estimate the percentage of their investments that might be returned.

But John Pingree, chairman of the board of investors, lamented that the court had rejected an earlier investor-proposed plan that would have had them take over the apartment properties and manage them until the market improved and they could sell them.

"If we could have taken that asset back and managed it, we believe we could have come out about 100 cents on the dollar or more," he said. "Our estimates now are it will be under half that."

Now, investors say the current proposed sale would create tax liabilities for some of them before they even receive any of their money back.

Beckstead responds that receivers aren't able to "time the market" with sales, and that he's restricted by decisions Jenkins has made. Opposition by investors to his first sale plan may in the end cost them money, he said.

"The recovery to the estate under that initial plan that I put together was better than they are getting now," he said. "That didn't go through in large part because of opposition from the investors."

He also points out that the receivership has cut management expenses for the apartment buildings in half and straightened out the enterprise's books.

"The wealthy [investors] can afford to hire lawyers ... so can they spend the time and money to try to shape the outcome to their benefit," he said.

Pugsley also said investors often forget "who the bad guy is. If there weren't any scams there would be no need for receivers to clean everything up."

—

Rights case • In a third major case out of Utah, the Federal Trade Commission in December 2010 sued St. George businessman Jeremy Johnson, his I Works company and others, with Robb Evans & Associates of Los Angeles appointed as receiver.

The receiver has spent about $5.8 million since January 2011, while so far recovering about $15.5 million, meaning 37 percent of the recovered money has gone to fees. Robb Evans has billed for $2.57 million and their attorneys, $3.1 million.

Attorney Karra Porter is asking the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals to rein in the I Works receiver.

Porter, who represents Johnson's wife and family as well as I Works and other entities though not Johnson himself, alleges the FTC has been strong-arming defendants into settlements in I Works and other cases she's studied by using receiverships to strip them of assets and take control of evidence needed to mount a legal battle.

"I've been appalled at what their normal practice appears to be," she said. "Not just this case was handled in a weird way or inappropriately … It's their template."

—

Reforms? • Beckstead is withdrawing from the Management Solutions case to serve a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

He says some reforms of the systems might be in order, though he and other receivers, attorneys and Jenkins say the system works well.

Klein laments a system in which, "I have to sue innocent people in order to get money back for people who are more innocent." But he sees no real alternatives at this point.

Hoole, the attorney for investors in the Management Solutions case, sees possible systemic reforms, including ensuring investors ability to participate in proceedings.

"Investors should have the opportunity to have a seat at the table," he said.

Reforming the receivership system

Federal Judge Bruce Jenkins has more than 40 years experience on the bench of U.S. District Court for Utah and in federal bankruptcy court. In an interview, he suggested ways to improve the receiverships system in fraud cases, though he believes the system generally works well.

Increase funding for regulatory agencies • Agencies sometimes settle cases with defendants without them admitting guilt, meaning that burden falls on the receiver who has to use investors' funds to prove allegations that Jenkins feels should be the province of regulators.

Getting federal judges involved in receiver selection earlier in the process • Often, an agency comes with a situation that requires immediate attention and, as a result, the judge has to make a hasty decision, Jenkins said.

Reform Utah law governing limited liability companies to make it easier to find out who the actual owners are • Present laws allow for the "layering" of ownership so receiverships end up spending a lot of money trying to "penetrate the maze." —

VesCor Capital

Receiver appointed May 5, 2008

Fees/expenses as of Nov. 8, 2013

Receiver Robert Wing • $1.3 million

Prince Yeates law firm • $3.56 million

Forensic accountant Gil Miller • $971,079

Total fees (including other costs) • $7 million

Recovered • $14.98 million

Expected additional recovery • $2.5 million

—

Management Solutions Inc.

Receiver appointed Dec. 15, 2011

Fees/Expenses as of Dec. 31, 2013

Receiver John Beckstead • $1.1 million

Holland & Hart law firm • $4.8 million

Deloitte forensic accountants • $2.5 million

WSRP accountants • $742,808

Total • $9.3 million

Recovered if plan approved • Unknown, but likely tens of millions

—

I Works

Receiver appointed Jan. 13, 2011

Fees billed through Nov. 30, 2013

Receiver Robb Evans & Associates • $2.25 million + $212,075 expenses

McKenna Long law firm •$3.2 million, plus $146,900 expenses

Accountants • included in receiver total

Total fees and expenses • $5.8 million

Recovered net of expenses • $15.4 million (continuing)