This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Washington • With a stroke of his pen on April 12, 1929, President Herbert Hoover preserved some 4,200 acres in southeastern Utah, heralding the area's gigantic arches, natural bridges, spires and other unique wind-worn formations.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt expanded the new Arches National Monument to create what is now a national park so treasured that Utah is synonymous with the park's iconic Delicate Arch.

Republican and Democratic presidents have used the 1906 Antiquities Act — which allows the chief executive to bypass Congress — to set aside monuments across America, including the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument that President Bill Clinton designated in 1996 to the ire of many southern Utahns.

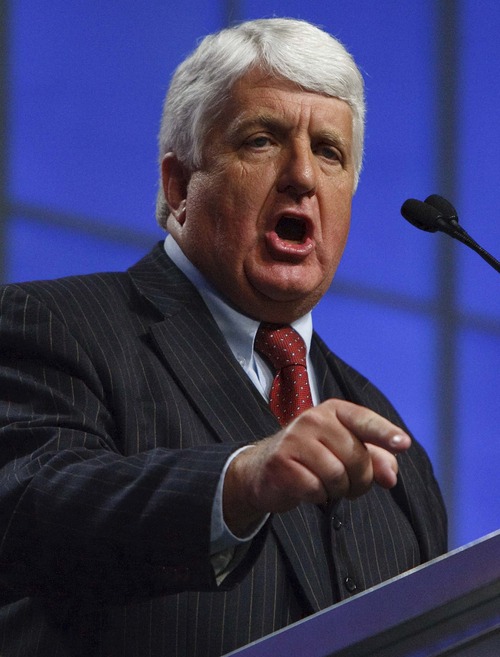

The House is expected to vote Wednesday on a measure by Rep. Rob Bishop, R-Utah, to add new restrictions on that power, forcing a president to go through a stringent environmental review before a new monument is created under the act.

Environmentalists argue Bishop's proposed change would have dramatic impacts on efforts to protect pristine areas.

For some Utahns, though, it's a welcome move.

"The whole concept in 1906 was to protect antiquities, and how it's got to a point where a president and a small handful of supporters can take that kind of action — man, that's an abuse of what I think the original intent of what that was," says Lynn Jackson, chairman of the Grand County Council. "There's no collaboration. … No need to talk to anybody. It's Just a stroke of a pen and it's a done deal. That's just not the way our democratic process should work."

—

Debate • Bishop's bill, which will be up for debate midday Wednesday and a final vote in the afternoon, would force any new monument proposed by the president under the Antiquities Act to go through an environmental study first, and restrict a president to one monument per state during a four-year term without a congressional waiver.

An emergency clause would allow a president to name a small monument — 5,000 acres or less — without an environmental review but the designation would expire after three years without Congress' approval.

Supporters of the Antiquities Act, many of whom had advocated for President Barack Obama to wield the power more often to preserve lands, say Bishop's measure is simply an attempt to hinder a president's ability to protect valuable areas of the country.

"Under this bill, Utah's 'Mighty 5' National Park promotion campaign would be cut to the 'Lonely 1,'" says Scott Groene, executive director of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, referring to the state's tourism promotion of the national treasures. "All of our parks except Canyonlands started as national monuments. This bill would gut the legal authority that has protected some of Utah's best and most popular places."

Filmmakers Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan, who produced the Emmy Award-winning documentary series, The National Parks: America's Best Idea, argued in a Capitol Hill newspaper this week that during their research they found many people who opposed a national monument to later regret their decision. Bishop's bill is a dangerous move, they add.

"To weaken [the Antiquities Act] would be the biggest blow to land conservation and the future of national parks since the time the act was first passed," Burns and Duncan wrote in The Hill newspaper. "History also shows that during those hundred years, there have been repeated attempts to weaken or abolish the Antiquities Act. Fortunately for the nation, those efforts have been consistently turned back because, again and again, the act has proven itself crucial to the historical moment."

Bishop calls the arguments against his bill "silly" and "spurious."

—

Public input • "All we're saying is that the president has to get public input first," Bishop says. "Nothing prevents the president from using his pen. He just has to [go through] the public process before he does it to work out the problems ahead of time instead of trying to fix everything once it's been made."

To that point, Bishop's supporters point out, the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument was established without a review under the National Environmental Policy Act while Andalex Resources Inc., which wanted to mine up to 120 million tons of coal from the region over a 45-year period, spent $8 million on such a study trying to get federal approval to mine in the area before the monument existed.

A report by the GOP majority of the House Natural Resources Committee two years after the designation noted that Clinton's move "illustrates not only an abuse of the Antiquities Act, it also provides an example of how the Clinton-Gore Administration uses NEPA as both a sword and a shield, abusing and manipulating the process to achieve its political ends."

The Republican report continued that the effects of the monument aren't known because no study was done on the local impact.

State Rep. Ken Ivory, a West Jordan Republican who has railed against the federal government owning land in the West, says the Antiquities Act shouldn't exist in the first place but at least Bishop is trying to do something about it.

"If it's going to apply and be used as a weapon against the private use and control of property, certainly the president should do no less [than required in the proposal]," Ivory said.

"It's definitely a step in the right direction to add some openness and transparency and have some debate on the issue."

House passage of Bishop's bill is likely — Republicans hold 233 seats, Democrats have 199.

But in the Senate, where Democrats are the majority, the legislation may well never get to a vote.