This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Vigilante violence was endemic to 19th-century America — with Mormons on both ends of it.

Members of the new faith that emerged in upstate New York in 1830 saw their homes destroyed, their lands lost, their women brutalized and their prophet murdered, but they also perpetrated "inexcusable" attacks of their own — including the infamous Mountain Meadows Massacre — sometimes in retaliation and sometimes in the wake of fiery rhetoric from top LDS leaders.

This is the view put forth in a new "Gospel Topics" essay, posted by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints at lds.org.

It is part of a series of recent articles produced by the Utah-based faith to explain sometimes-sticky historical or theological LDS issues. Other entries include the church's teachings about the nature of God, its former ban on blacks from its all-male priesthood and its long-discarded practice of plural marriage.

The current essay, titled "Peace and Violence Among 19th-Century Latter-day Saints," spells out signature episodes in LDS history of bloody acts committed by and against Mormons, and attempts to put them in "historical context."

"While historical context can help shed light on these acts of violence, it does not excuse them," the essay states matter-of-factly. "… What was done here long ago by members of our church [at Mountain Meadows] represents a terrible and inexcusable departure from Christian teaching and conduct."

Non-LDS historians found much to praise in the new essay.

"In a compressed space — with useful documentation — the piece deals openly and unabashedly with history of a church that includes lots and lots of violence in its past, especially against Latter-day Saints but also by Latter-day Saints," says Sarah Barringer Gordon, professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania who has written extensively about Mormon history. "The connections between the two kinds of violence are explored helpfully."

The article mentions tensions in Missouri between Latter-day Saints and their neighbors that ultimately led to the murders of LDS founder Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum. It describes a Mormon paramilitary group known as Danites formed to respond to rampaging Missouri mobs.

It also looks at the love-hate relationship between Mormon settlers in Utah and American Indians. These believers viewed the natives as a "chosen people" and descendants of major players in their faith's signature scripture, the Book of Mormon. Still, they occasionally battled over land and resources.

"Peaceful accommodation between Latter-day Saints and Indians was both the norm and the ideal," the essay says. "At times, however, church members clashed violently with Indians."

Conflicts with the U.S. government reached their peak in early 1857, when President James Buchanan sent an army to replace Joseph Smith's successor, Brigham Young,as territorial governor amid reports that Mormons were rebelling against federal authority. The so-called Utah War spurred widespread worries among Latter-day Saints of a return of Missouri-scale persecution.

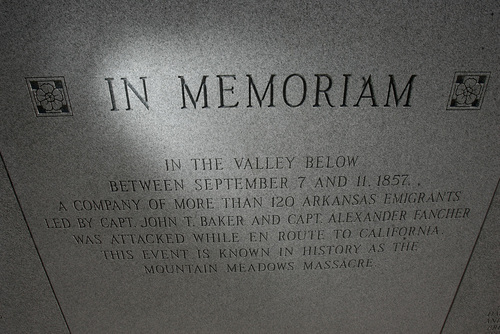

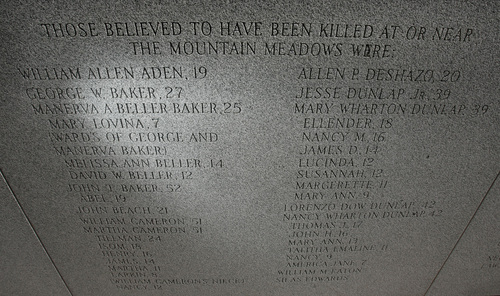

The most violent episode in Mormon history was known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

In September 1857, a southwestern Utah Mormon militia laid siege to a wagon train of emigrants en route from Arkansas to California. Verbal clashes ensued over grazing and supplies, and some of the emigrants threatened to join the approaching federal army. LDS Stake President Isaac C. Haight sent a militia major, John D. Lee, to attack the company.

They did, slaughtering 120 men, women and children on Sept. 11, 1857.

The essay asserts that a rider had been sent to Young before the raid to seek his guidance and forestall an attack.

"The express rider returned two days after the massacre," it says. "He carried a letter from Brigham Young telling local leaders to 'not meddle' with the emigrants and to allow them to pass through southern Utah."

The LDS Church excommunicated two members for the carnage and a grand jury indicted nine. But only Lee was convicted and executed.

The essay points to the critically acclaimed 2011 book — "Massacre at Mountain Meadows" by historians Ronald W. Walker, Richard E. Turley Jr. and Glen M. Leonard — and concludes that "while intemperate preaching about outsiders by Brigham Young, George A. Smith and other church leaders contributed to a climate of hostility, President Young did not order the massacre."

Western historian Will Bagley strongly disagrees with that assessment.

"Brigham Young ordered the massacre as a political move," says Bagley, author of "Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows," "and the church has been putting forth to this very day the same alibi — the letter — that Young created as the crime was underway."

But acknowledging that "Mountain Meadows was Mormon violence, and that there were Danites," says Stanford historian Richard White, "goes further than they have ever gone."

Penn's Gordon, White and others do note some glaring omissions and one-sided accounts.

Gordon argues the essay could have explored more fully early comments about "blood atonement."

That teaching, as espoused by Young and others, was that "some sins were so serious that the perpetrator's blood would have to be shed in order to receive forgiveness."

The topic could have used "more explanation and more details," Gordon says, especially in light of "how widely it is discussed in the literature" of the era.

White, an expert in Western American history, says that tales of horrific crimes attributed to the Danites were exaggerated "but not all accusations were wild or untrue."

Until nonpartisan historians are allowed to examine the evidence in LDS archives, he says, "we will never know what was really going on. Were they using armed bands to eliminate those who had defected?"

White maintains the essay also underplays the Mormon role in triggering the violence in the Midwest, framing it all as persecution of the believers.

"It turns out," he says, "Missouri was in the midst of a civil war."

Jan Shipps, an American historian specializing in Mormon history, also believes the essay downplays Mormon culpability before the exodus to Utah.

"In the description of the Hawn's Mill Massacre and the Missouri War," Shipps says, "you would think the Mormons were sweet and charming to everyone."

Some of the actions came in response to early Mormon rhetoric.

When Missouri Gov. Lilburn Boggs' issued his "extermination order" against the Latter-day Saints, Shipps says, he was echoing the language Mormon leader Sidney Rigdon had used in a sermon, talking about the church's enemies. Joseph Smith had Rigdon's speech printed and circulated among the faithful.

Today's church, she says, would "find it difficult to accept the amount of hostility that was expressed by Mormons after they were driven from Illinois."

This essay, Shipps says, "goes a long way to helping Mormons see their ancestors as part of American Western history — with all its flaws."

Twitter: @religiongal —

Highlights from the essay

• Mobs expelled Mormons from Missouri in 1839 after the governor issued an "extermination" order and from Nauvoo, Ill., in 1846, two years after the murders of LDS founder Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum.

• At least 17 Mormon men and boys were slaughtered at Hawn's Mill in October 1838 in Caldwell County, Mo. "Some Latter-day Saint women were raped or otherwise sexually assaulted during the Missouri persecutions," the essay notes. "Vigilantes and mobs destroyed homes and stole property."

• The rampaging Missouri mobs prompted some LDS leaders and members to form a paramilitary group known as the Danites. These vigilantes "intimidated church dissenters and other Missourians," the article states. " … Mormon vigilantes, including many Danites, raided two towns believed to be centers of anti-Mormon activity, burning homes and stealing goods." Joseph Smith likely approved of the Danites, but historians doubt he was "briefed on all their plans and likely did not sanction the full range of their activities."

• After their Missouri woes, Latter-day Saints formed a militia, the Nauvoo Legion, to protect themselves in Illinois. Feared by many outsiders, this legion, nonetheless, did not retaliate after the mob murders of the Smith brothers and eventually disbanded.

• Tensions between Ute Indians and Mormons mounted in 1849 after a Latter-day Saint killed a Ute known as "Old Bishop, whom he had accused of stealing his shirt. Back-and-forth skirmishes and accusations eventually prompted Mormon leader Brigham Young, who enjoyed friendships with several Indian leaders, to authorize "a campaign against the Utes." "A series of battles in February 1850 resulted in the deaths of dozens of Utes and one Mormon," the essay states. "In these instances and others, some Latter-day Saints committed excessive violence against native peoples."

Source: LDS Church essay "Peace and Violence Among 19th-Century Latter-day Saints"