This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Baltimore • Rep. Elijiah Cummings gets a laugh when he points out that Utah has a problem with wild horses.

That's not something fathomable for the folks in inner-city Baltimore where the more pressing concerns are crime, unemployment and poverty. On the flip side, people in Provo don't suffer from food deserts, or areas where grocery stores, and healthy food, are lacking.

"I bet you've never heard of a food desert," Cummings says to Rep. Jason Chaffetz, who shakes his head no.

Baltimore and Provo are almost polar opposites, politically, racially, economically — and yet they are represented in Congress by two men likely to be the top leaders on a powerful House committee next year. Cummings, a black Democrat, speaks with the gusto of a pastor; Chaffetz, a white Republican, tosses red meat when he talks.

The Utahn is possibly the next chairman of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee in the next Congress; Cummings is likely to remain the ranking Democrat.

So in an effort to forge a relationship, and learn how each other ticks, the two are embarking on a sort of listening tour to each other's district.

First up, Baltimore, the largest city in Cummings' district where a small boy hawks bottled water in the median of a busy road, signs warn neighbors not to play ball in the street and home after home is boarded up. Cummings knows this isn't what Chaffetz is used to, but the Democrat also wants to help the Republican get a glimpse of what life is like for his constituents.

"I want him to understand that life throws a lot of us some tough curves but yet there are still people who refuse to stay down, who do everything in their power to get back up," Cumming says at a stopover Monday at the Center for Urban Families, which helps those wrestling with parenthood and relationships. "It's like struggling like a baby to walk. You get up, you grab a chair, you do whatever it takes and then you get up and once you stand up, you reach a new normal."

Cummings has sparred many times — sometimes in yelling matches — with Oversight Chairman Darrell Issa, who is term-limited from continuing on as the committee's leader. But Cummings sees a potentially better relationship with Chaffetz.

"I would say this if Chaffetz wasn't in the room," Cummings says. "Chaffetz is not Issa. You know, he's not."

—

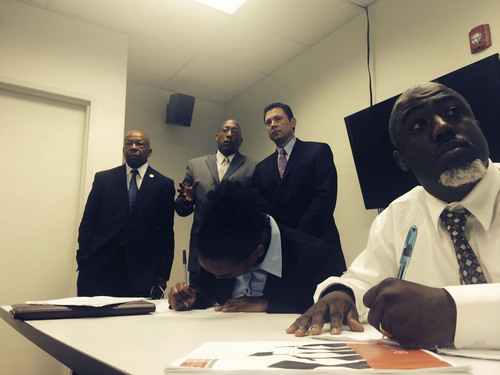

Challenges aplenty • About 30 students, dressed in their finest business attire, sit in a classroom at the Center for Urban Families. Some have had criminal troubles, all of them wanted some guidance to improve their lives. The white board in the room proclaims a lesson for today: "Direction determines destination, not your intentions."

"Not enough people see the direction they're going and have the audacity to turn around; many go a lifetime," Cummings tells the group as he and Chaffetz stand before the group.

The Utah congressman, the only white person in the room, talks about how his district is the youngest in the country, has six ski areas and two universities. He quickly realizes the students have a rule in the classroom: They must introduce themselves before speaking or put a $1 bill in an empty water jug. Chaffetz whips out his wallet to pay up. "I didn't say my name," he laments.

Baltimore has a 7.8 percent unemployment rate, one of the highest murder rates in the country, and a festering drug problem that inspired the HBO series, The Wire. The students at the Center for Urban Families are trying to get their lives back on track, get a good-paying job and make a better life for their kids.

"I can tell the moment I walked in here you guys are doing good stuff," Chaffetz tells them. "It's inspirational seeing good people doing good things. It's even more inspirational to see people who had challenges overcome them."

It's nothing like Chaffetz's home district, where the biggest city, Provo, has an unemployment rate of 2.9 percent, is growing in population and often ranked as one of the best cities to live in. But that's the point of this trip: perspective.

"We don't see brownstones likes this in Utah," Chaffetz says, glancing at the homes during a short drive between stops. "You just don't. It's just different."

Actually, you don't see brownstones in Baltimore either; they're rowhouses, like townhomes that share walls. It was all a bit foreign to the Utah Republican.

"I think it's important that, you know, as we try to move towards a more perfect union that we have a better understanding of the people, and the issues that confront them, from our various districts," Cummings says. "And it's important for me to understand what Chaffetz, [what] his district is like, so I can understand what his motivations are because I always try to put myself in the place of folks who may have opposite views so that I can understand them."

Cummings points to a favorite saying: "You cannot lead where you do not go and you cannot teach what you don't know."

—

Agree to disagree • The Oversight and Government Reform Committee serves as the House's top investigative panel, constantly requiring the administration, federal agencies and recipients of federal funds to account for problems that surface. More to the point, it's the committee where scandals are dissected, or, as some critics charge, created.

Chaffetz, currently the head of a subcommittee, would have unilateral power to subpoena testimony and records as full committee chairman, a position he's publicly campaigning for. He's one of the more vocal and media-savvy members. And while he might not be as confrontational as Issa, the current committee leader, Chaffetz has been just as eager to decry the administration's response to the terrorist attacks in Benghazi, Libya, the targeting of conservative groups by the IRS and the cross-border gun-running that happened under the Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms' Fast and Furious program. Democrats, like Cummings, complain often that the GOP is just trying to find fire where there isn't even smoke.

If Republicans maintain control of the House this November, GOP leaders are likely to pick the new chairman from three candidates: Chaffetz, Mike Turner of Ohio and John Mica of Michigan. Cummings hasn't scheduled tours of his district with any other candidates for chairman, but his office says there's an open invitation for any committee members to do one.

Cummings sees hope in Chaffetz's potential chairmanship.

"We're going to disagree," Cummings says of his Utah colleague, "but I can tell you when you know something about a person and where they're coming from and why they have the motivation they have, it makes it easier to work together. It's only common sense."

For his part, Chaffetz says the two get along "fabulously."

"I think it will be a strength, not a negative," the Utahn says of their relationship. "You break bread with him and you get to know him."

The two dined the night before in Baltimore's inner harbor, away from the more gritty areas of town. Over steaks, Chaffetz talked about the public land battles that Utah faces; Cummings talked about the need to raise the minimum wage.

At the Sandtown Winchester Senior Center, Cummings jumps right into the issue he knows the crowd is concerned about.

"I'm not saying that this is Congressman Chaffetz's idea, but there have been some of our Republican friends, and actually the president talked about it for a while, talked about cutting Social Security benefits," Cummings says. "Now don't be shy. If you have concerns about that, let us know."

Chaffetz notes he wants to reform Social Security so it will be there for generations to come but promises the seniors that he doesn't want to cut their benefits. He then pivots to his district, its younger population and booming economy.

"We're very blessed, but we have our challenges too," Chaffetz says. "We deal with issues that you don't deal with here. We deal with public lands issues. Seventy percent of our state is owned by the state or federal government. And that's kind of hard to fathom, to understand what that looks like."

It was for the crowd, the same way it was hard to understand that an overpopulation of wild horses was something that plagued any place in the 21st century. The Utahn saw he was losing the crowd.

"I'm going to go ahead and guess you were more Barack Obama fans than you were Mitt Romney fans," Chaffetz says, earning a strong laughter. Indeed, 76 percent of Cummings' district voted for Obama; 78 percent of Chaffetz's backed Romney.

Cummings swooped in.

"I think its safe to say that this is a group of people who like Barack Obama," Cummings said. "A lot of them never dreamed, come on, be honest, never dreamed, never dreamed that in their lifetime that they would see a man of color in the White House. It was a very proud moment."

After the applause, Chaffetz, who had traveled the country stumping for Romney and against Obama, noted he didn't vote for the president. But, he added, it was monumental to elect the nation's first black president, and especially important that Obama's race wasn't the driving factor.

It was similar, to some degree, Chaffetz said, to Romney, a devout Mormon, securing the Republican nomination.

"I'm a Mormon," Chaffetz said. "You may not have met somebody who is a part of the Mormon church but I will tell you what, when we saw Mitt Romney become the Republican nominee for president of the United States and his background in religion was not the No. 1 issue — he didn't lose because he was Mormon, he lost because he didn't get enough votes — that's an important thing, too."

The reverse of this conversation is likely to take place later this fall, when Cummings visits Chaffetz's 3rd Congressional District, home to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' Brigham Young University and a majority Mormon population. Chaffetz isn't sure yet where he'll take his counterpart on a tour, but is excited to show what matters to his folks back home, too.

It'll be Cummings' first time in Utah, like it was Chaffetz's first visit to Baltimore's non-touristy areas. The congressmen know they aren't going to convert the other, but they both pledged to understand why they differ, and just maybe that will make it easier for them to get along as they confront some of the most partisan issues of the day.

"We shouldn't be afraid of disagreeing," Chaffetz says. "But how you do it is imperative. We can disagree but we can't be disagreeable. We can vet out those differences. We've got to ultimately try to figure those out. It's a challenge for both of us long-term."