This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

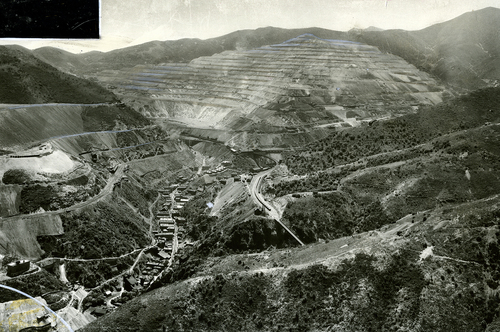

Before Utah Copper Co. (Kennecott) expanded the Bingham Canyon Mine into one of the world's largest open-pit copper mines and consumed the ground beneath the towns and homes of the people who helped build it, Bingham Canyon was noisy, dusty, vital and full of life.

In 1896, Salt Lake City entrepreneur Samuel Newhouse recognized copper's future and shipped out the first copper sulfides from Highland Boy Mine in the Oquirrh Mountains.

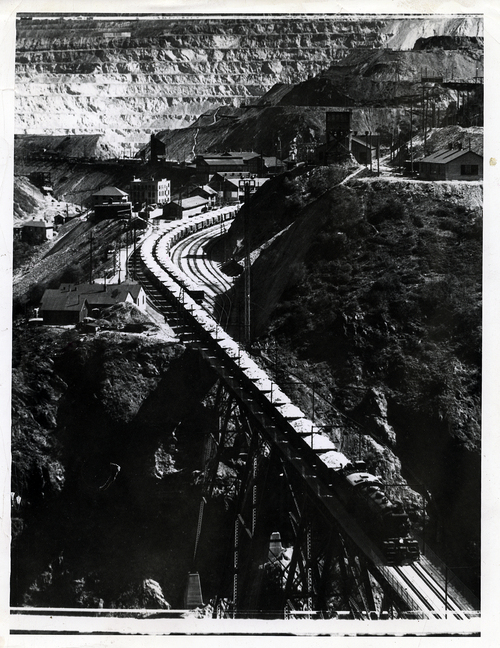

In 1906, Utah Copper mounted steam shovels on railroad tracks to strip away 75 feet of surface rock to expose large deposits of low-grade ore and provide a profitable way to convert the copper-laced mountain into a copper pit.

Defined within the narrow canyon's steep walls, the town of Bingham Canyon was the hub of the mining district. According to early Bingham resident and writer Marion Dunn, Bingham was a town "attached to a mine [with] an umbilical cord [called] Main Street, a long, twisty thoroughfare that was simultaneously entrance and exit."

Flanking the lengthy, 20-foot-wide street were mining and oil businesses, office buildings, mercantile shops and pharmacies, theaters and cafés, gambling dens, saloons and a brothel. There was a City Hall and post office, a hospital, a movie house, a grade school and a high school. Wherever housing could be built, it was — from shacks and shanties, apartment complexes and bed-and-boards to wood homes and fine estates.

Several miles up the canyon, Main Street forked. The right road branched toward the towns of Carr Fork and Highland Boy. The left fork, continuing on as Main Street, led to Copperfield, neighboring Dinkeyville, Telegraph, Terrace Heights and a bank of communities known as Japanese Camp and Greek Camp.

By the late 1920s, the canyon's population soared to 15,000 people, including 65 percent who were foreign born representing more than 25 nationalities.

"It was a melting pot of diversity that built and showcased the West," June Holmes Garrity told me recently in her Millcreek home. "In Carr Fork, my grandparents lived among Finns, Swedes and Norwegians. Highland Boy housed Austrians and Italians. In Copperfield, where my father, a manager of the U.S. Smelting, Refining and Mining Co., was given a company-owned home, our neighbors were Italians, Greeks, Japanese, British and Scandinavians."

Born at Bingham Canyon Hospital in 1929, Garrity attended the Swedish Lutheran Church. "There were so many Scandinavians," she said, "we had a full live-in pastor."

She remembered union troubles that gave her father ulcers and strikers "standing in the cold snow with their wives bringing them food." She harked back to the sound of blasting and whistled warnings that sent her scurrying to nearby shelters to wait out the flying rocks. She recalled mining disasters, train accidents, avalanches and floods that plagued the place.

But she most fondly recollects her childhood, when her friends were as diverse as the township she grew up in, and Bingham was a wonderland.

"Copperfield was a community where everyone left their doors open and the lights on. In the wintertime, after a hard snow, we would get our sleds and 'belly boost' all the way down to the heart of Bingham's business district, a mile away. Then we'd wait to see if Dad would drive down in his car and pull us back up the road," she said. "When Kennecott built a vehicular tunnel under the mountain joining Copperfield to Bingham, we'd put on gloves and roller-skate down the sidewalk clear through the mile-and-a-half-long tunnel."

In the summertime, they played Andy-I-Over, kick-the-can and hopscotch with a treasured taw. They picked chokecherries for pies, went down to the tunnel to sell pieces of galena (fool's gold) to tourists and scoured the hillside, where wildflower bloomed, the air was clean and no one told them when to come home.

To deepen the pit, in 1958, Kennecott demolished Copperfield. The other towns vanished and, in 1971, crews wiped Bingham Canyon off the map. Nothing left now but memories.

Sources: Arilla Bullock Jackson's "Copperfield," Marion Dunn's "Bingham Canyon" and Scott Crump's "Bingham High School."

Historian Eileen Hallet Stone is the author of "Hidden History of Utah," a compilation of her Salt Lake Tribune columns. She may be reached at ehswriter@aol.com.