This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

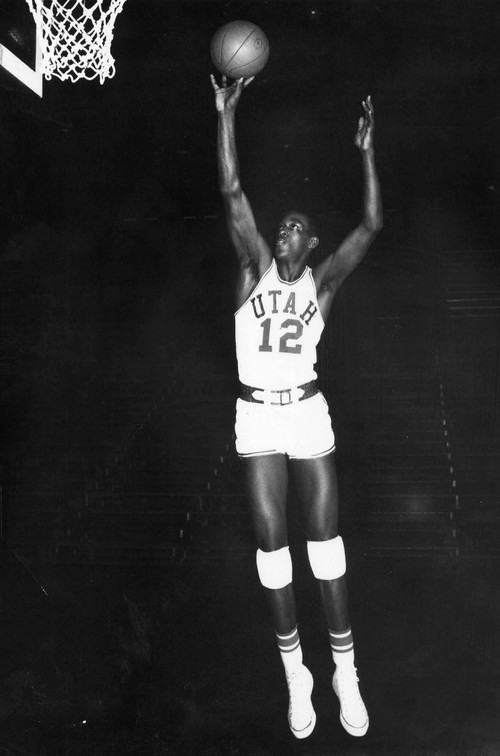

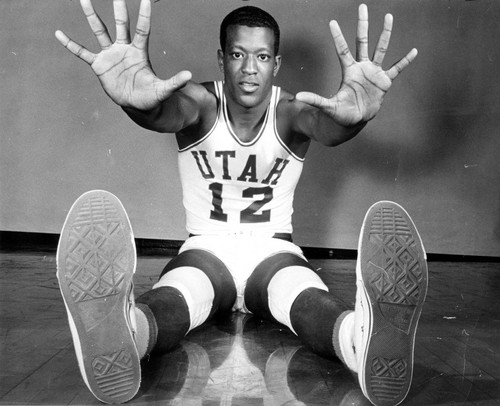

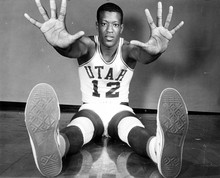

Billy McGill, a 6-foot-9 center who broke statistical and racial barriers as a college basketball star at the University of Utah, has died.

A Utes sports department spokesman confirmed the death on Friday of one of the program's all-time greats who muddled through ups and downs in his professional and personal life. He was 74 years old.

Former Utes coach Jerry Pimm called the big man who once led the NCAA in scoring, "one of the greatest players I've seen or been associated with."

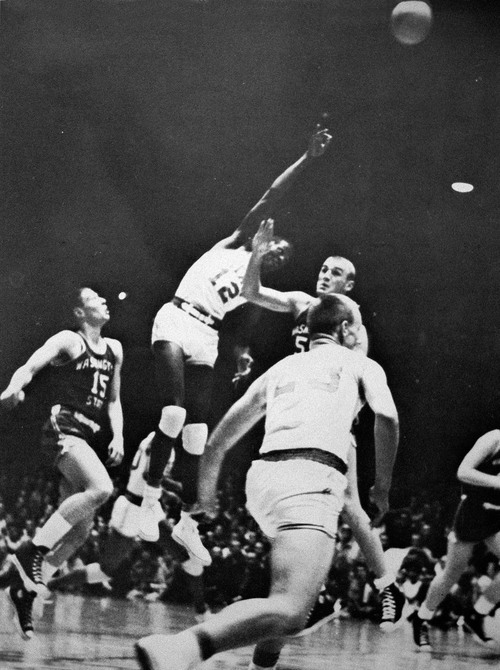

Known to fans as "The Hill" owing to his size and phenomenal paint presence, McGill's greatest success came at the U., where he was the star player of the Runnin' Utes and made the 1961 Final Four with the team. He was the first African-American to play basketball at Utah, and he was inducted as a member of the program's all-century team in 2008. His jersey, No. 12, has been retired by the Utes.

As a senior, he averaged 38.8 points per game, which only three other players have ever eclipsed in the college ranks. He also averaged 15.0 rebounds per game that year. He was one of only seven college players to notch more than 2,300 points and 1,100 rebounds in only three years. He averaged a school-record 27 points per game for his career.

In basketball circles, McGill is widely credited with innovating the use of the jump hook shot, a tough-to-block move that made him a dominant offensive player. McGill's mostly unrivaled back-to-the-basket game formed the foundation of Utah coach Jack Gardner's chief offensive strategy: "Feed the post."

"I learned quickly you played more if you fed the post and gave Billy the ball," said John Allen, a former Utes teammate who is now the chief statician for the Utah Jazz. "I tried to help rebound for him more so he didn't get as tired from all the shooting."

In one of McGill's most famous games, he scored 60 points his senior year at BYU in a 106-101 win for the Utes. Pimm told a reporter after the game, "If Billy had only scored 58, we would've lost." It remains the highest individual scoring performance in program history.

McGill had a reputation as a quiet teammate, a man who was hard to know. But Allen said he came out of his shell in competitive environments, from the team's after dinner bouts of ping-pong, to the thrilling close-call rivalry games.

"I remember we were at Montana, and I hit a buzzer-beater to win the game, and Billy came rushing at me and tackled me," Allen said. "That was the most exuberance I saw from him. He wanted to win. It was wonderful when his personality came out like that."

McGill was one of the early high school basketball phenoms, winning two city championships at Jefferson High School in Los Angeles while earning player of the year twice.

His legend was built in the L.A. Summer league, scrimmaging against the likes of Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain as a teenager.

Pimm was among those who saw McGill in the early days, and thought his promise held no bounds.

"He was quick as could be, and it helped him block shots and make shots" Pimm said. "He wanted to play out there. He loved the game."

McGill's promising college career gave way to a pedestrian professional tenure, as he struggled through a knee injury that limited his production after being picked first overall in the 1962 NBA Draft by the Chicago Zephyrs. McGill played only five professional seasons, three of them in the NBA.

He later struggled financially, going into debt and living on the streets in the early 1970s, as told in his autobiography, "Billy 'the Hill' and the Jump Hook." He was employed in the aircraft industry from 1972 through late in his life, but never had the wealth or security that goes hand-in-hand with being a top draft pick today.

Eric Brach, a lecturer at West Los Angeles College, co-wrote the autobiography, and said it was hard for McGill to share his struggles with his college teammates who had seen him at his greatest. When they were writing the book together over the course of several years, Brach said most were surprised to hear that McGill had endured so many trials looking for work after his basketball career.

The book, published in 2013, brought McGill a kind of peace in the final year of his life.

"It says a lot about the man that he went through all that, and it was important to him to finish that," Brach said. "But I think he wanted to be remembered by how great a player he was and how much he loved playing at Utah. After the book, it seemed like some people and media lauded him in the way he should have been lauded throughout his life."

He is survived by his wife, Gwen McGill. His grandson, Ryan Watkins, played basketball at Boise State this past season.

Twitter: @kylegoon