This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Moab • Between bites of his Dutch-oven dinner, Rep. Elijah Cummings throws out a bomb of a question and then a knowing wink.

"So, what do all of you think of Washington?"

The Maryland Democrat looked to his left and his right, surrounded by Republican leaders in rural Utah. State Sen. David Hinkins, R-Orangeville, sought a polite answer, a friendly grin showing below his white Stetson.

Finally, he manages: "It's a nice tourist spot."

Bruce Adams was equally chummy, a hand draped over the back of Cummings' chair in the old country dining hall. But the San Juan County Commission chairman wasn't going to dodge the question.

"They are the enemy. They are uninformed," he said. "That's why it is refreshing to have your eyes and ears on the ground here."

And that was the point, at least part of it.

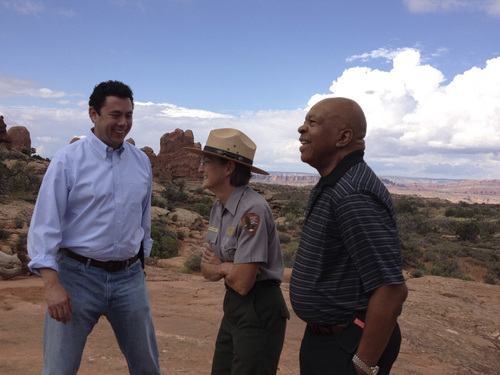

Cummings came to Utah this past weekend to tour the congressional district of Republican Rep. Jason Chaffetz, to understand the political disputes unique to the West and to talk to people such as Hinkins and Adams who view the federal government as a hostile partner.

But Cummings also hopped a Southwest flight to Salt Lake City on Sunday to strengthen his relationship with Chaffetz. The two are key members of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee. If Republicans keep control of the House this November as expected, Chaffetz is one of three candidates to replace Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif., as the committee's chairman. And Cummings is likely to remain the panel's top Democrat.

Cummings has had a tense, combative relationship with Issa, who has spearheaded investigations of the attack on U.S. diplomats in Benghazi, the IRS scrutiny of tea-party groups and other conservative complaints against the Obama administration. He'd like to have a more constructive partnership with the next chairman. Chaffetz, a media-savvy politician who has been by Issa's side during some of the most contentious investigations, doesn't have the reputation of being as polarizing as the current chairman.

Cummings put it this way recently: "Chaffetz is not Issa. You know, he's not."

And that may be why he invited Chaffetz to see his Baltimore-based district in late June.

He took the Utah Republican to a community center, where poor people were trying to learn skills to improve their lot in life. They visited a senior center, where they discussed the value of Social Security, and then they talked to people receiving treatment at an AIDS clinic.

Chaffetz, who never had been to the rougher parts of Baltimore, saw a world unlike anything that exists in his expansive congressional district that runs from southeastern Salt Lake County to the Four Corners area.

Cummings shared a favorite saying: "You cannot lead where you do not go and you cannot teach what you don't know."

—

Crash course • Cummings doesn't know Utah or the West or much about rural issues. This weekend's venture was a world unlike anything that exists in his densely urban district. His district is dominated by Baltimore, where he has lived his entire life, and is as overwhelmingly liberal as Chaffetz's is conservative.

After his plane touched down at Salt Lake City International Airport, a Chaffetz staffer ferried Cummings to an ancillary airport, where the state's Beechcraft Super King Air was ready to take off.

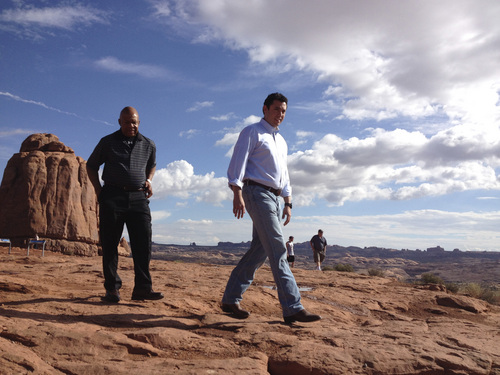

This six-seater twin-propeller plane became a classroom as Chaffetz pointed out features of the land below, explaining the recreational uses of Utah Lake, the forests in Wasatch County, the coal mines in Price and, ultimately, the redrock around Moab, where the plane landed.

But the conversations weren't about geography. Chaffetz gave his guest a sampling of the political disputes that put the state's political leaders, who are mostly Republican, at odds with environmentalists and many federal bureaucrats.

Endangered species. Mining. The overpopulation of wild horses. The threat that President Barack Obama could create a new national monument.

It was new to Cummings. All of it.

—

The rural view • Just minutes after landing in Moab, Cummings looked out the passenger-seat window of a black Suburban and asked, "What is this? What am I looking at?" as he pointed to a mesa in the distance.

A bit stunned at the question, Chaffetz described how the wind and water have eaten away at the sandstone over thousands of years to create these natural wonders.

"It's beautiful," Cummings said.

Chaffetz invited a group of county commissioners and local leaders to join them for that Dutch-oven buffet that was so good both congressmen went back for seconds.

And before boarding a boat for a night cruise of the Colorado River, Chaffetz's media aide, MJ Henshaw, asked Cummings: "What would happen if you walked in your district with boots and a cowboy hat?"

"They'd think I lost my mind," Cummings said with a big laugh.

The river tour included a light show and a narrated history of the area that was both educational and a little lovey-dovey.

"I didn't know I would have such a romantic time with you on the river," Chaffetz said early Monday as he opened up a more formal discussion in which rural commissioners took five minutes to explain their viewpoints on federal issues, adding more depth to the dinnertime conversations.

Cummings had no problem picking up on the theme that emerged. These leaders want more control of the lands in their areas, which are overwhelmingly owned and controlled by the federal government. They believe faceless bureaucrats create onerous rules that hamper their way of life and inhibit the growth of their economy.

No one in this meeting represented a different political point of view. There were no environmentalists calling for the protection of disputed, scenic lands. No voices argued that oil and gas development contribute to climate change.

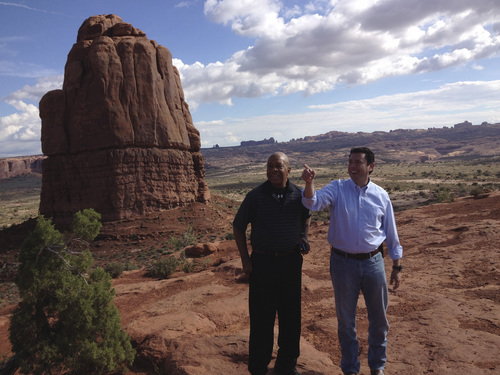

Chaffetz acknowledged people with those views live in Utah, too, but portrayed them as absolutists, interested in locking down lands that should be mined. He noted that he's working with Rep. Rob Bishop, R-Utah, on an ambitious initiative that would seek to resolve some of these long-standing disputes, creating some energy development areas in exchange for millions of acres of wilderness.

Seeing an exchange of ideas from politicians of opposite parties is heartening, said Deeda Seed, associate director of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance. But she wished the conversation included voices such as hers.

"Clearly Congressman Cummings got a very one-sided view of the issues around public lands," she said, "because he didn't get to hear from people who are very concerned about the protection of these amazing places."

Cummings heard from people such as Grand County Council Chairman Lynn Jackson, who said he's proud of the recreation economy around Moab, but wants to supplement it with more oil exploration. He hoped Cummings left the discussion "with the understanding that Western lands and counties with so much federal ownership need a seat at the table."

"We just have to strike the right balance," Chaffetz said.

Cummings responded: "We are the guardians. ... We've got to guard what we've got."

And he lamented the current state of politics, where, he said "we talk past each other — and then you die."

Cummings found it fascinating that some ranchers could trace their family lineage back seven or eight generations, saying "that is foreign to me." His father was a sharecropper and his forefathers were slaves. He doesn't have the same connection to one way of life as some of the ranchers in rural Utah.

"It gives them a perspective. 'We've been doing this a long time. This is our family business,' " Cummings said on KSL Radio. " 'Maybe the federal government doesn't fully understand my history.' "

He said policymakers and bureaucrats should make an effort to get to know these people before instituting rules that could change their way of life.

"At least they would feel a level of respect and dignity," Cummings said, "and I think that's what it is all about."

Their conversation took a more personal turn on the flight back to Salt Lake City. Cummings asked about religion — Cummings is a Baptist and Chaffetz is a Mormon. Cummings asked how LDS missions work. Later in the day, Chaffetz planned a private lunch with Cummings and Gov. Gary Herbert before taking his guest on a private tour of the LDS Church's Welfare Square, showing how the state's largest religious institution takes care of its needy.

Breaking the political cycle that has strangled Washington will take trust and understanding, and Chaffetz and Cummings hope that they have built some of that during these visits.

Chaffetz hopes that he may be able to persuade Cummings, a powerful Democrat, to vote his way on a few issues dear to rural Utah.

"That's hard to do with people who haven't been here," Chaffetz said. "He's been here and that will make all the difference."