This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Eugene Schwarz would rather sleep outside.

The 50-year-old veteran camps in the foothills south of Salt Lake City, where mice nibble on his Latin dictionary and Agatha Christie novels.

A few other pests come by: Boys from the neighborhood over the ridge occasionally steal the paints for his model bomber airplane. And hikers pass through every now and then.

But Schwarz, a New York native with a bachelor's degree in philosophy, has stayed in his spot for more than a decade.

Utah officials aiming to end chronic homelessness in 2015 concede the number will never go to zero. Health and housing workers say a few people are bound to fly under their radar, and others don't want to come inside.

ONLINE CHAT: Homelessness experts and Tribune reporters discuss the "Housing First" strategy and the next phase in getting more people out of shelters.

Lloyd Pendleton, director of the Utah Homeless Task Force, likens the homeless count to job market measures: An unemployment rate as low as 4 percent counts as full employment.

"It's the same way with the chronically homeless," he said.

Schwarz is one of those who prefers to stray.

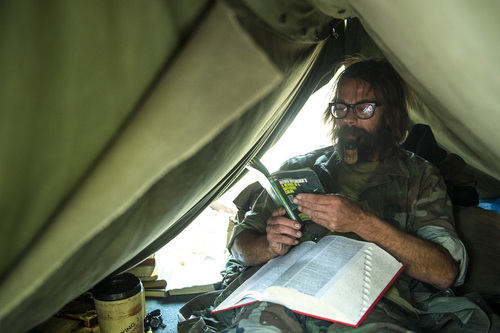

On a recent Saturday, his day off from cleaning University of Utah toilets and county buildings, Schwarz offered rare visitors a cup of coffee and a look around his tent in a ravine near the interstate.

"Everything's within arm's reach, so I can cook and read and sleep," he said. "I like living outside because it's a simpler and cheaper way to live. Most people pride themselves on their possessions. Me, I pride myself on what I know, books I've read.

But he stays close to the city. Diabetes and a love of Cicero bind him to health care from Veterans Affairs and city library book sales.

Besides, he says, he doesn't have the survival skills to break away completely.

Schwarz sleeps close enough to the road that he needs ear plugs to doze off. Officers have told him to move his camp farther up the canyon once or twice, but he rarely sees them.

The son of a secretary and a hair dresser, he joined the Army three decades ago to pay for college, serving briefly in Germany. He studied at the University of Arizona at Tucson before pit stops in St. George and Kanab. Schwarz first came to Salt Lake City about 20 years ago for a summer job digging graves.

In the mornings, he mixes hot cocoa and instant coffee with spring water, or drinks straight from the nearby brook, insisting it's never made him sick. He stays warm with a propane tank, and lean with a vegan diet of beans, peanut butter, pasta, and unfrosted strawberry Pop-Tarts from Wal-Mart or Smith's.

He never had kids or a wife, drinks a beer a week at most, and shares holiday meals with a family who first spotted him years ago when his bike broke down on the freeway.

Every other Saturday, Schwarz scales cliffs with a rock-climbing group of veterans.

After college graduation, Schwarz stopped in southern Utah, where he made friends with Troy Knapp, the "mountain man" now serving a federal prison sentence after breaking into southern Utah cabins, stealing guns and whiskey and taunting authorities for years.

Schwarz says the two traded books. He considers Knapp a "nice guy" with a small frame who saw guns as an "equalizer." The two no longer keep in touch.

Schwarz' ideal society would be contained in one giant, stark building surrounded by total wilderness because "I like the contrast." The Salt Lake Valley and its mountain walls are the next closest thing, he said.

Living in the mountains, he figures, allows him to save up for retirement and either a librarian's degree or a master's degree in philosophy.

Utah's chronically homeless

This year, the Utah Department of Workforce Services reported 539 chronically homeless, down from 1,932 in 2005 — a 72 percent drop.